Бесплатный фрагмент - To love

One day of childhood

Benedikte!

(Good Luck!)

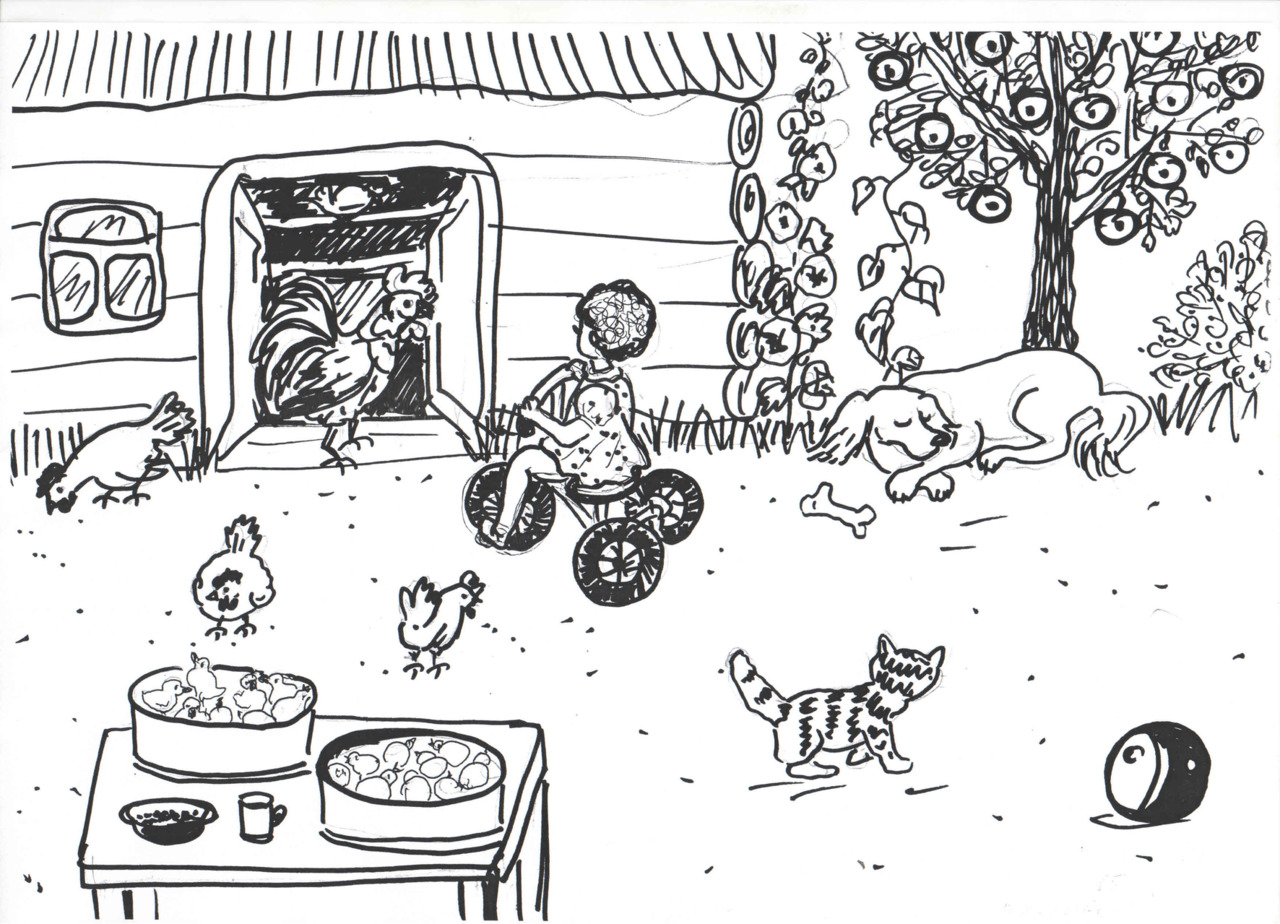

I‘m five. It`s morning time. I hear our cock crowing through the dream. It vociferates loudly, good-heartedly. But it`s so quiet still; a gentle, cool night breeze sheaves the curtains on the window. I sweetly continue sleeping.

About an hour later I smell the chicken broth. Oh, how I like this soup from our home cribs. Mom feeds dad, and then they will go to work, I think, and go on sleeping.

I arouse, when the sun stretches out its rays through an open window and wakes me up. I look out the window and sniff the morning smell of yellow high flowers, planted by mother near the house. Our nanny Frosya sleeps on the nearby bed in my bedroom. My brother’s cradle stands near it.

Mom is forced to work; earlier the maternity leave was short. There`s a new dress of crepe de Chine on the headboard. Mummy sewed it up yesterday evening, and when I was falling asleep, she whispered in my ear, “Put it on tomorrow.” I put my head in the neckline, and the dress, made of natural silk, is gently sliding over my childish body, warm after sleep.

I leave the children`s room, pass the sitting-room, drop in the kitchen, then through the corridor to the lumber-room, where mom cooks dinner on the stove in summer.

I want to check everything out. Hasn`t anything changed for that night? Hasn`t the lacquered board near the sofa stopped creaking? I step on the floor, the board kindly creaks — my house greets me!

I climb on the sofa, study the father`s geological map in detail. All the geological squiggles are in situ. My finger moves across the map. I find the word, which mom showed me yesterday — it means Kuibyshev.

I run to the inner porch there`s a glass of milk and bread baked by mom under the towel and a chicken leg on the plate on the table. The aroma and yellow chicken broth circles is the smell of childhood, happiness and peace.

I start flipping through the books, which mom brought from Kuibyshev, when she went to submit the report. I leaf through a book about textile: there are many pictures of beautiful fabric. I like the stores “Fabrics” up-to-date, like to feel, sniff, rub between the fingers silk, cotton, being convinced of the most valuable`s eternity.

I take the book about a huge whale, leaf through it. Then I sort out the new pencils, there are a lot of them — multicoloured, shiny — thus joy slowly fills my little soul.

I come up to the turntable; put the vinyl record with Chukovsky tales. I sit down next to the chair, listen to the narrator`s voice and look at freshly blown rose on the green bush, which grows in a large clay pot near the turntable.

But the most interesting place for me was a huge lumber-room. There was a trough with sunflower seeds in husks and without on the floor. But I do not put them in my mouth, they’re dirty. However, I know if mom washes and fries the seeds, I will slabber them, and I know, that the hens and a cock eat them too.

My father’s hunting dog Puljka (pellet) lies on the mat without a collar; it is a noble German breed. It has smooth brown fur and long hanging ears. Dad said it`s good at looking for ducks, which are very far, through the wood, on the lake. I sit down on Puljka`s back and try to lift its drooping ears with my soft palms to make them like neighbouring Rex has. The dog licks me — the owner`s daughter.

I walk to the bench; there in two big sifters under the gauze yellow creatures are peeping — chickens and ducklings. I begin slightly clamping yellow wads in my hands. I kiss these “furry balls”; the chickens are lemon wads and the ducklings are yellow. Having survived and again in the sifters, the chicks calm down.

Soon mom comes for dinner. I`m fed, and she allows me to walk near the house. I sit down on the bike, which stands at the front porch, it gleefully creaks under my bare feet — it’s not forgotten. I ride round a huge yard to the shed.

The only one cock stands near the entrance. It is very beautiful with green, blue and red feathers. The cock looks at me askance and regrets, that it can`t prove its prowess and peck this Mistress`s cute daughter.

I quickly get on the third ladder stair in the henhouse, and gently put my hand under the white layer. The hen starts softly clucking, as if taking offense at the check. It has already demolished three eggs, which I grope my little fingers.

Having greeted the hens, I go watching my treasure, which is a great old jewelry box with beautiful pictures, two small brooches, slides and other treasures. Then I visit the garden behind the outdoor kitchen. I pluck green currant there on the run, examine, how much the flowers have grown for the night. Then I sit down on the bike and ride to the orchard in front of the house. There I touch small unripe apples with my fingers.

We have no gooseberries, but our neighbours the Pudovkins have. I reach out over their fence and tear off an unripe berry. I look at the window to find out, whether the neighbour aunt Nyura watches me. She has been at the window for a long time and threatens me with a finger. I think to myself: “You`re greedy, Pudovkina”.

I go out from the orchard, close the gate to the copper hook. I open the main gate, carry the bike, sit down on it and leave for the road, which runs between neighbouring houses. There are ten meters to the hummock.

There`s my favourite forest and the Kynel river behind the outskirts. The snowdrops, odorous snow-white may lilies, bird-cherry, wild berries, hawthorn appear and grow in the forest in different seasons. There is a small lake, where cheerful frogs croak. My favourite river is waiting for me. But I’m afraid to go there alone. I`ll go with my parents in the evening after their work.

My girlfriends Tanya and Valya run out from neighbouring yards. And the games in a big skipping rope begin. The two twist a heavy rope, and I jump in the middle. I jump for a very long time, until others begin to oust me. Then we play hide- and- seek. We hide behind the logs, the shed, in the high grass, behind the house. After it we play the ball, then “I know five girls’ names”. We run one by one and nicker.

It`s Friday, the parents came from work early, we go to the river. I go barefoot by a path, which is smooth, polished with lots of feet. Then we go down the path to the forest from the hummock. The path under feet, closer to the river, is getting warmer, yellow sand — fiery. I rush into the river. I flounder about in the river moving bravely, happily, deliriously.

Fresh river water envelops the body, tired for the whole day. Good old grandfather Kynel washes away long summer day`s dust with its watery arms from me like his granddaughter. Mummy`s watching me on the bank. I bravely dive, trying to swim under the water. Having typed the air, I try to plunge deeper into the cold river water. I breathe in river, seaweed, summer and the Sun smell, the smell of childhood. I swim, dive, swim — enjoy! My teeth start chattering from the cold, apparently because of being in water for a long time. Shrinking from the cold, I come out of the river and lie down on the fiery sand. After a while, I begin to warm on the hot sand… and again rush into the water.

It’s time to go home. The parents need to do something about the house. Relaxed, sweetly tired, I go home with my parents. It`s a lovely warm July evening, the middle of summer! We come home and immediately go into the orchard. There`s a huge table and wooden Viennese chairs in the garden under the kitchen windows.

Mom lays the table. Daddy carries little Sasha, the nanny follows him. We are having supper, listening to the crickets and faraway sounds of a cuckoo. I fall asleep right at the table. Father carries me into the house. Another one, such a happy long day has passed. It seems that it will always be this way.

My First Man

Advertisy is a good teacher. (Proverb)

We all come from childhood. And there is nothing affecting than reminiscences of the minutes, hours and days spent in that gentle time. People have dreams about their childhood until the old age, it lives in the person, while his soul`s alive.

I was fortunate enough to have my childhood in almost wild nature. And my world cognition passed through the things of real nature.

My father graduated from the Moscow Institute of oil and gas named after Gubkin. He was allocated in geological exploring expedition in Samara region, village Georgiyevka, with its picturesque places: the Volga-River`s affluent Kynel and the vast forests around with lakes in them.

My dad was given a swish cottage for those times with a garden and an orchard, which stood beside the “geologists’ office” on the village outskirts near the forest.

I (Ljusenka-the-bead) was born in this cottage. I was loved immensely. As the saying goes, “chocolate lay about the corners”. And being blonde, brown-eyed laughter, I loved back the parents and the world around.

I liked the river in particular. It was strong, big, with brash flow and large and small funnels of swirling water.

Dad with mom went to work and left me with an old nanny Frosya. I was disallowed to go outdoors, but after their leaving I immediately scooted with neighbouring children in the forest and to the river. The way to the river lay through the forest callous path and then a hot sand track.

In one place there was a shallow, the river`s special gift for kids, where we, preschoolers, puddled about.

Of course, I couldn’t swim. So I came up with to go into the water, further away, face the bank, dive, swim a bit under the water, and then pushing away from a firm sandy bottom, approach the bank. So I decided to do then.

But the road was blocked by an old man. He was very thin, with a big grey beard. His screwed-up lids asked: “Why did you come without parents?”. I began to bypass him and went into the water just where the bank abruptly turned in the pit with whirling funnels. I didn’t notice how moved deeper and deeper, plunging for several times. I wanted to push away from the bottom with my legs and swim to the bank.

But the Kynel pushed my light body with its huge water hand away from the bank. Suddenly I felt myself pulled into the funnel and carried away by the flow. I started to dive, push away from the bottom, emerge, grasp the air, water, realizing that I was drowning. I thought that the old Kynel was punishing me for disobedience and resigned like a lamb with no scream and cry for help, being exhausted.

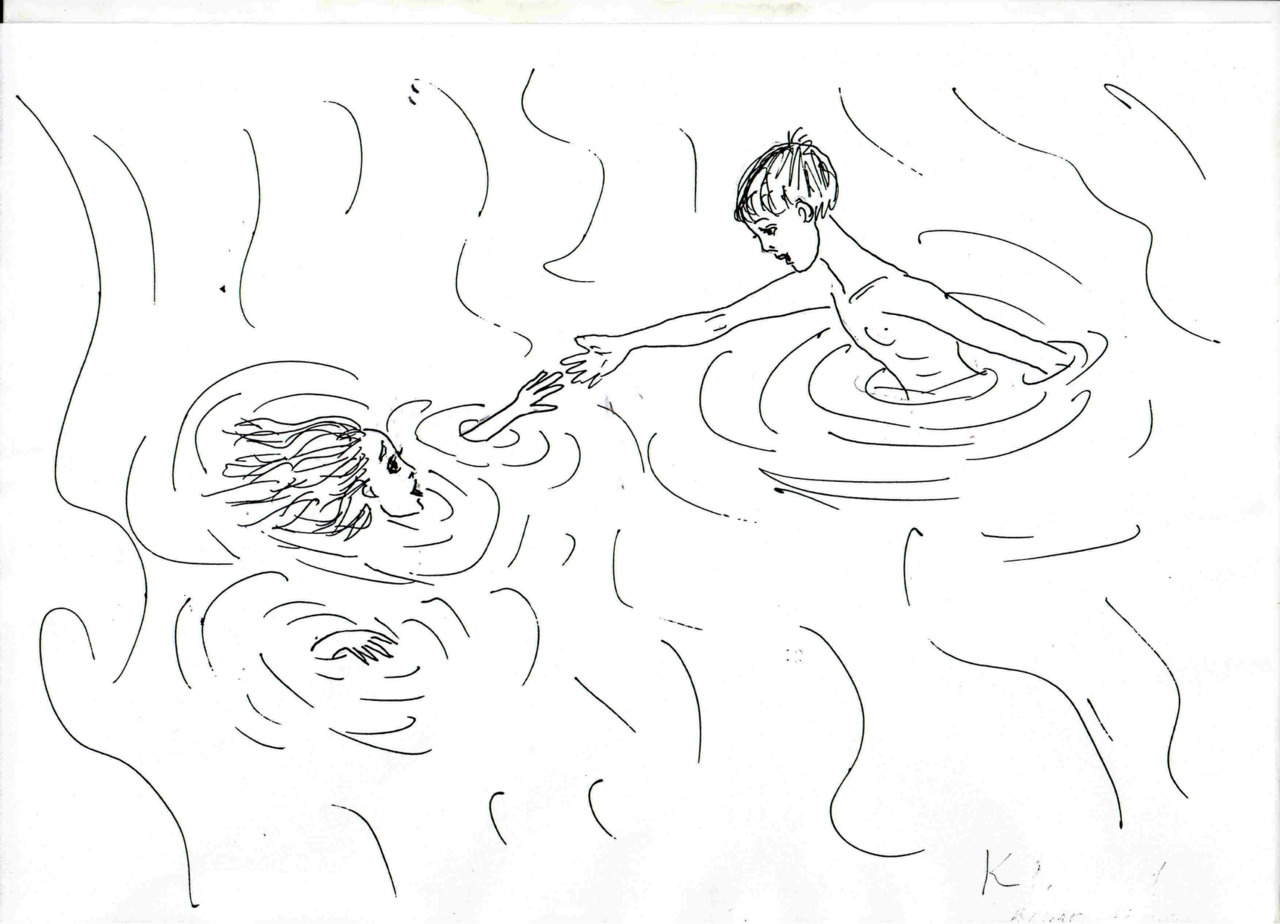

The last time under the water I didn’t touch the bottom. Emerging from my last strength I saw a neighbouring boy holding out his hand to me.

He stood at the border between the pit and the shallow. He looked straight in my eyes confidently, strictly and adultly. I grabbed his palm, and he pulled me out of the water.

The boy’s surname was Kaltman, I don’t remember his name. But I will always remember his black-eyed glance, black-haired head and firm hand. He saved me being not much elder than me. He became the angel who whispered “live”, and he didn`t know about it.

Many years passed, and the life passed, but I often remember the glance of this boy.

The real men, faithful, strong, reliable, must act like that. Men should always pull out a woman from another stupidity.

Such was he, the five-year-old boy. His father was a driver; he drove my father to the oil rigs.

Exhausted, I came out as crawled out of the water. I lifted my dress, lying on the hot yellow sand and trailed home by the forest path. In childhood everything seems otherwise. When I came home, I already forgot what had happened, and told mom nothing. Apparently the boy was silent, too. This incident was forgotten. Only later I realized that the boy saved my life.

Soon my father was offered to work in Neftegorsk, and we moved.

I‘ve never been to those beautiful places, where the river Kynel flows, where the cuckoos sing in the forests, and there`s a crystal — clear, tear-like water in the forest lakes.

I’m happy, that I spent my childhood there, and happy that I was surrounded by remarkable people and that wonderful boy, who simply held out his hand and gave me life.

Mother’s love

Onсe in autumn a herd of horses grazed near a gas processing plant sanitary zone. Among them a bay mare with a foal visibly stood out. A baby-horse of the same brick-red suit as its mother walked among the herd, larked and played. It often ran up to the mother and, burying in the udder, wagging its ponytail, enjoyed mother’s milk. From time to time it ran away and pinched verdant grass.

Something unexpected happened to the environment. The control torch was blown out on the technological gas condensate pipe, whether from a strong wind or for some other reasons, but it happens in gas processing.

Gas condensate mixture was spread by the wind at a far distance, and it fell on the ground as the drops of rain. The gas condensed grass turned green. The herd of horses began to move away from hydrogen sulfide site. But a little foal, unaware of the horse life difficulties, quickly began to pinch and swallow toxic grass.

The herdsmen saw what`d happened, when the kid, trailing behind the herd, lowered its head and moved hardly on its thin legs. It, probably, poisoned at once the whole throat with gas condensate and made only quiet sounds like a snore. Some time later it fell to the ground with weak signs of life.

The herdsmen, prudent people, carved the foal — its meat and skin were taken for the economic needs. But the remains were not buried. They were negligently lying near the straw pile, where carved.

The bay horse separated from the herd. The mare had been looking for and calling the foal with a loud neighing for a long time, but did not hear its usual response.

Meanwhile, the herdsmen drove the herd away from the pestiferous place. The horse visited the ravine, where the foal was pinching grass. Sniffing the road, she ran to the straw pile, where the remains of her baby lay. The horse neigh sounded loudly, anxious and tearful. The bay mare stood on her hind legs, walked in circles, hoofed and hoofed the ground. She made the guttural sounds similar to crying with a loud and plaintive wheezing. She hoofed a large pit around the remains, leaned on her foreleg knees, inhaling air, and shook her head. The bay horse was crying. From her eyes large tears flowed. Then again she stood on her hind legs, neighed loudly, hoofed and galloped towards the leaving herd, lifting up the dust, moving away farther and farther from the hapless place.

The bay horse was restless all the night. She`s wandering with her head low, nostrils wide open, drawing air in, snored, making guttural, prolonged sounds. At dawn, jumping over the fence, she rushed along the former village routes to the ravine, where she`d left her foal. Meeting no one there, she stood and flinched all over. With her head high she loudly and moodily neighed, calling someone native and close to her. There was no answer.

Meanwhile, Korneich hurried to the stable in the morning. When he came, he saw the bay standing near the corral fence away from the herd, which snuffled, chewing the green grass mass, stored up by the stableman since evening. Watching the horse, Korneich noticed in her and in her behavior obvious changes. She became unruly. The horse often beat her brethren with the hooves, bit their necks and always stood against putting to the cart.

For the winter the mare became quite different from one that used to be. Glossy, of the brick-red suit, healthy and strong, now she lost weight and became a sort of reddish with separate sites of felted wool on the hollowed sides. She`s absent in the corral for the second day. The horse has disappeared.

Бесплатный фрагмент закончился.

Купите книгу, чтобы продолжить чтение.