Бесплатный фрагмент - They Call Me Mzungu

Anna Vladimirovna Demina (1980) – MD, PhD, infectious diseases specialist, virologist, scientist, and writer. She has authored more than 50 scientific publications. Anna was born in Novosibirsk, Russia. She spent her childhood in Belarus. Graduated from Novosibirsk State Medical University.

She completed her postgraduate studies at the State Centre for Virology and Biotechnology ‘Vector’ in Koltsovo, Novosibirsk region. Her dissertation research was carried out in Stockholm, in the Swedish Institute for the Control of Infectious Diseases. She defended her PhD thesis in 2012. Her post-doctoral work was done at the University of David Ben-Gurion of the Negev, Beer-Sheva, Israel. During her professional career, she worked in Uganda, Africa, where the first story ‘They call me Mzungu’ was written. Later new stories appeared and became part of this book.

Genre – non-fiction, autobiography, memoirs, where stories from Anna’s life and professional experience of an infectious disease physician are fascinatingly described.

PROLOGUE

The plane landed in Washington Dulles International Airport. I passed through passport control, picked up my luggage and went into the arrivals hall. A sign with my name rose above all people who met arrivals. I didn’t expect it, but it was very nice, so typical of Dave (full name – David Franz). Of course, I would find and recognize him without any sign. He was so tall that he towered over people and so stately that it was impossible not to pay attention to him. I suppose he just wanted to cheer me up or to imitate an official reception. David Franz was an army colonel in retirement and a former Director of the United States Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases.

The story of how we met was reasonable for our professions. David came to Russia to give a lecture on particularly dangerous infections in the Novosibirsk State University. That day my scientific supervisor, Netesov Sergey Victorovich, asked me to interpret David’s lecture into Russian for it contained specific terminology that a usual interpreter might not have known.

After the lecture, we went to the science museum where I remained in the role of interpreter. In a bus, David sat next to me and we began our conversation. That was the moment when our friendship started. We would later recall that experience many times and name that day our ‘Karmic day’.

We had exchanged our contact details and after David’s return to America, we started emailing. We even established a wonderful tradition: ‘Thursday letters’. The point is, I worked as a doctor in the central clinic of a city and it was easier to reach by metro than by car, to avoid traffic jams. Every Thursday sitting in a metro car I was writing to Dave about my patients, news, activities, and he wrote me about his life.

Later we introduced my daughter Sofia to his granddaughter Anna. David’s older son Matt and his wife Amelia adopted this girl from China. Furthermore, they had adopted a Russian boy Kolya, and later their own child was born. Thus, they became a big family with three children. By the way Matt was born on the same day as I was. That is why Dave is always the first person who sends me birthday congratulations. So, I called Matt ‘my twin brother’.

Of course, we had video calls and I met his wife, Pat, by video link.

Pat is an incredible woman, so delicate and so stout of heart. She always glowed with a smile when we met. She danced in cheerleading, which is, in my opinion, the most interesting and difficult type of sports dancing. To me, cheerleading dancers are the consummate dancers. Now Pat teaches music to children. She also cooks delicious meals. She became for me a symbol of a inspirational woman. I suppose, behind every successful man there’s a woman like this.

In May 2017, I’d been invited to present a report at a scientific conference in Washington DC, America. David lived near this place, so I went there two days before the conference just to stay with him and Pat.

After a merry meeting at the airport, we headed to his car, where Pat had been waiting for us. We drove along the scenic road, past one-story mansions, like those from the Hollywood movies. David’s house was near a small lake and a green meadow, in a peaceful place, most suitable for rest. The house was built in a country style, with wooden beams and big wooden table in a living room. Several bedrooms were styled in vintage decor with plenty of decorative pillows on large beds. Therefore, instead of going for rest I began first by photographing rooms to show them to my family.

Dave was waiting for me in the kitchen, heating up the food his wife had prepared in advance. She also baked for us her famous brownies – typical American chocolate cakes. Covered with cream, they were like the greatest temptation, and whatever diet I’ve been on, I couldn’t refuse a brownie.

The evening became so cosy and conducive to conversation that we spent many hours, without stopping, telling each other stories from our lives. We recalled how David had changed my fate in a moment.

And then David exclaimed: ‘Anna, you should write a book of all your stories! It has to be published!’

‘Who, me? A book?’ I laughed back.

‘Promise me that you will write it!’ he didn’t give up.

I kept drinking my green tea with the brownie, smiling in return. I wasn’t sure yet that I would write this book; how I decided to become a doctor, and then a virologist. I would write how I worked in Africa, lived in Israel and Sweden. I didn’t know I would move from Russia to Israel, from Israel to Spain. No one had yet imagined that the Covid-19 Coronavirus pandemic will happen in the world, and how it will affect many destinies. We had no idea that many doctors would begin consulting by phone and video call and virologists will become famous people.

I was sitting in a cosy lake house in America at night in the kitchen of David Franz and had no idea that this night would become so fateful.

Dave, I dedicate this book to you. I want you to read it in English more than anything in the world. And I have a lot of work to do to get it published. However, this book really came into being thanks to your exclamation!

I. THE OLD DOCTOR’S TREASURES

The secret sooner or later becomes clear.

Socrates

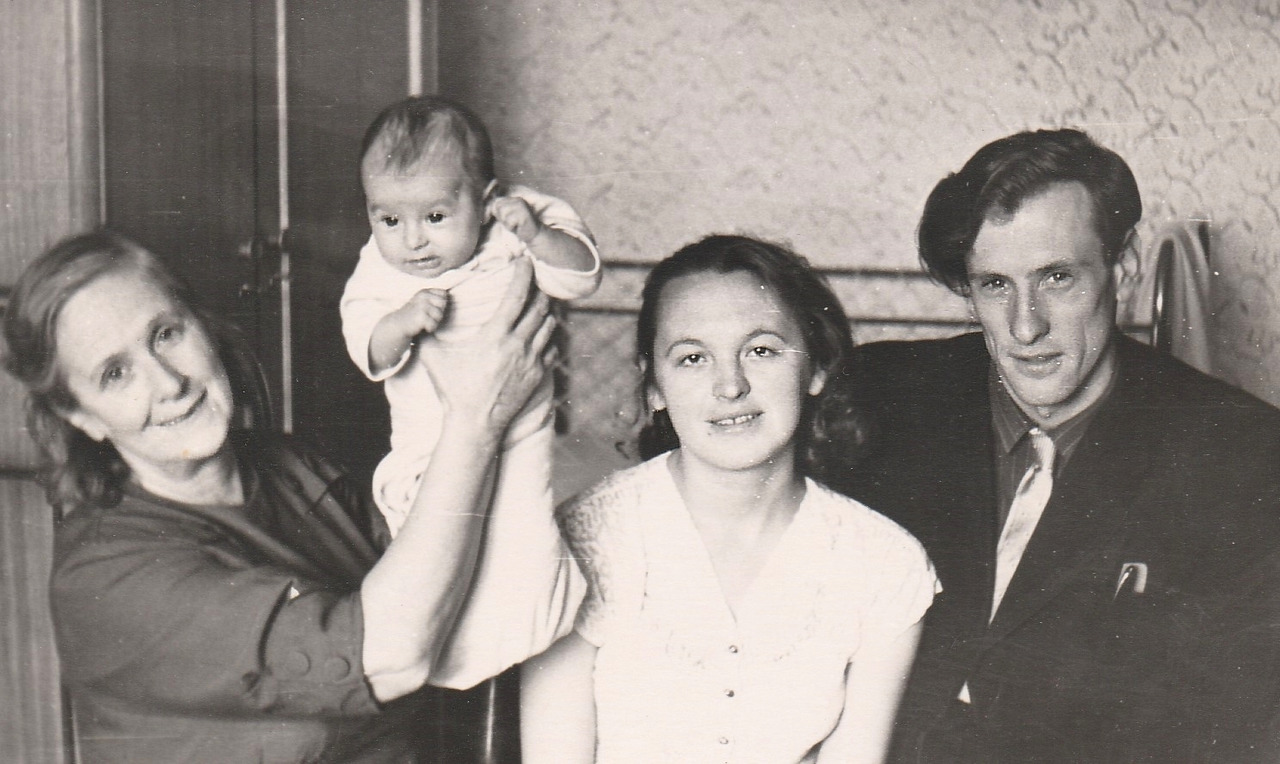

I spent my childhood in the south of Belarus in the city of Gomel with my grandparents on my mother’s side. Most of the time I was with my great-grandmother Nadezhda Alexandrovna Koltsova, who became my nanny. She was an infectious disease doctor and worked as a doctor during the Second World War. Great-grandmother treated diseases that are considered to be almost forgotten in the modern world: typhoid and typhus, cholera, malaria.

She was born in Moscow in a merchant family. Soon the family moved to Siberia. Her father Alexander Maltsev came from Moscow to Tomsk to open wholesale and retail tea shops of the famous merchants Gubkin and Kuznetsov. The family of my granny had a beautiful wooden house situated on Zagornaya Street in Tomsk, unfortunately it has not survived. Nadezhda received her education at Tomsk Medical University. She married a Lieutenant of the Kolchak’s White Guard – Grigoriy Vasilevich Koltsov, who had previously been a seminarian. Grigoriy had a beautiful and strong voice and sang in Opera after the civil war. He suffered a terrible fate of that time: he was declared an enemy of the people, arrested and executed by shooting. After the civil war and the loss of her husband, Nadezhda Alexandrovna with her son moved to Novosibirsk.

The peripeteia of life made her a strong woman. She managed the infectious diseases hospital. During the Second World War they received people evacuated from the war, including captured Germans and Japanese. All this happened in the context of an epidemic of tuberculosis, outbreaks of dysentery and many other infections against the backdrop of devastation, hunger and cold in Siberia.

I remember her strong hand, with which she painfully squeezed my palm as we walked down the street. I remember her medicinal syrups. I remember how many books she read to me, and at that time, I braided pigtails on the fringe of her carpet, which hung on the wall according to the old tradition. I always felt calm when I was with her. I cannot even say why I behaved quietly and obediently, seriously and thoughtfully. She was for me a symbol of endurance, wisdom and intelligence.

There was a large wardrobe in my grandmother’s bedroom. Its doors had locks with keys. The key to the main door was always hidden, and the door was only opened on special occasions. There was a metal trunk on one of the shelves in the wardrobe. The adults whispered that I shouldn’t touch it. Only they could open it. Apparently, there were treasures. At least, I thought so when I was five.

Once I made a deal with my grandfather to show me what was in the wardrobe and explain why I should not touch it. He took the key in his hand, looked conspiratorially at me, winked and put his forefinger to his lips. We quietly entered the great-grandmother’s bedroom. It was so exciting, as if we entered the Tomb of the Pharaoh, and were about to open the main cache. The key clicked in the lock, the door creaked, and the ‘treasure trunk’ shone in front of us.

Grandpa carefully took it out and placed it in front of me. He clicked two locks and opened the lid. It was a metal box for sterilizing medical instruments: inside were reusable glass syringes, reusable needles, surgical scissors with upturned ends, a scalpel, and a metal spatula for examining the throat.

‘What a precious thing,’ I thought, and all I wanted that moment was to have this particular set. It made a significant impression on me in childhood.

With the advent of the era of disposable medical instruments, I was finally given this box. I must say that all of my toys immediately became patients. Each doll and each teddy bear received an injection. Next came the scalpel. The toys were examined for the presence of internal organs. In general, my first dream was to become a surgeon. That is why I practiced.

Even while a student at the university, I got a job as a nurse in the surgical department of the 1st emergency hospital in order to have the most intensive practice. These were the dashing gangster nineties in Russia. The ambulances brought the beaten, injured in road accidents, cut with knives, broken bottles, wounded with firearms: ripped, torn and bloody. And, of course, there were hernias, appendicitis, ulcers, intestinal obstructions and other diseases requiring urgent surgical intervention. It was the best place to practice surgery and cultivate fearlessness.

The old doctor’s treasures influenced my choice to become a doctor. Perhaps, the main influence still came from my great-grandmother’s personality, because I chose the specialty of an infectious disease specialist instead of surgery and continued the family tradition. At the same time, I chose one of the rarest professions in the world.

II. CHERNOBYL.

NON-EVACUEES

The third angel blew his trumpet,

and a great star fell from heaven,

blazing like a torch,

and it fell on a third of the rivers

and on the springs of water.

The name of the star is Wormwood.

A third of the waters became wormwood,

and many people died from the water,

because it had been made bitter.

The apocalypse, chapter 8, verse 10–11

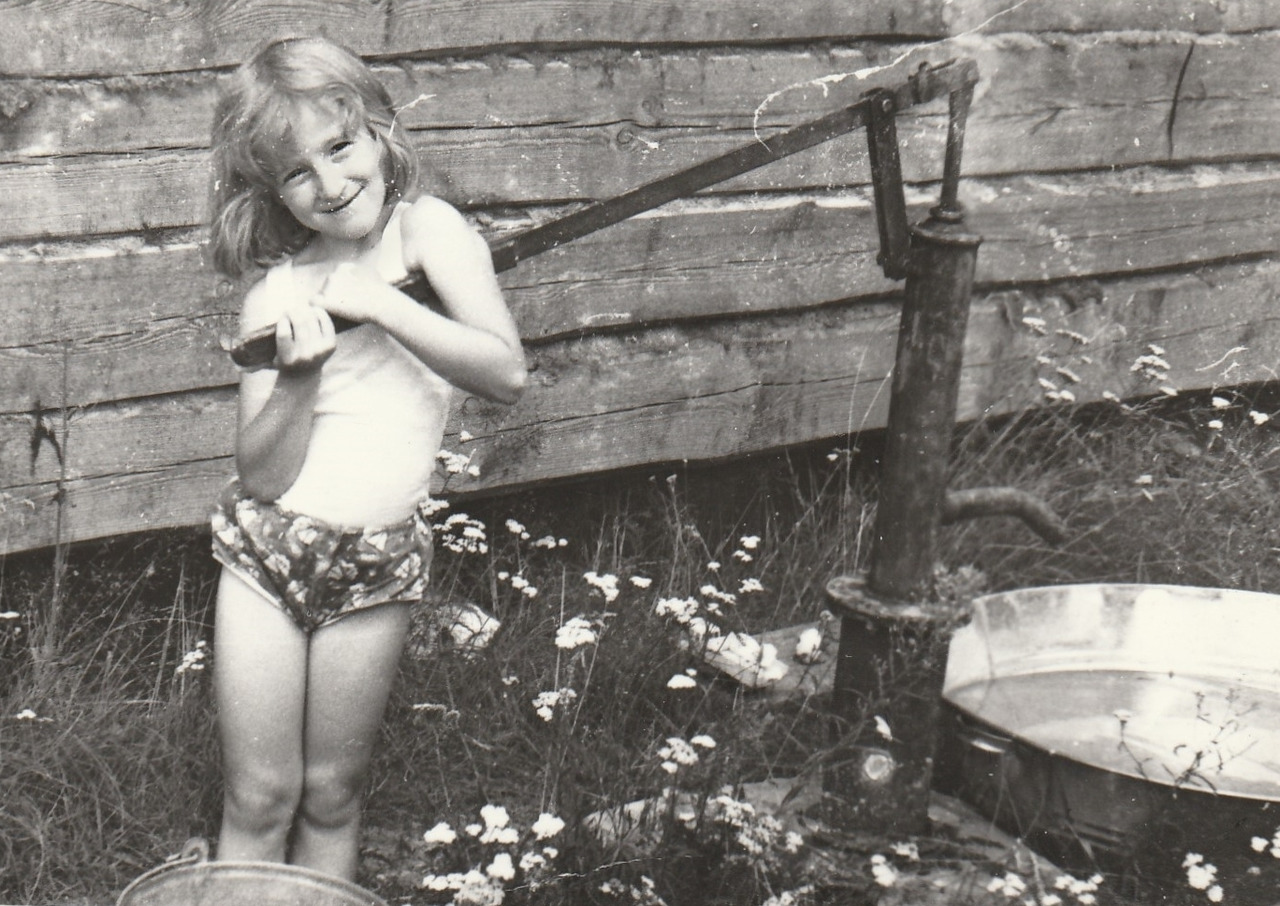

I will describe the Chernobyl accident as seen through the eyes of a six-year-old girl who lived in Gomel, Belarus, 130 km from Pripyat, where the Chernobyl nuclear power plant was located. ‘Chernobyl’ means ‘wormwood’ in Ukrainian.

These are shards of memories that should remain on paper for future generations to remember how it was.

On April 26, 1986, we were walking with other children on the street in the courtyard of our multi-storey building. A vile wind blew; it seemed that it carried sand and the sand pierced right through us. It was a strange wind, otherwise I wouldn’t remember it. I also remember that I wanted to go home and find shelter from it.

After that day, adults began to behave strangely. They gave me red wine to drink, forced me to eat a can of seaweed and a half glass of walnuts. Maybe I would have forgotten about it, but from that day on, every day all summer I’d be given some of these products. By the way, now I do not drink red wine and do not eat seaweed.

At the dacha (Russian name of country house) an interesting device, ‘Dosimeter’, appeared.

The dacha was situated in a wonderful area with pine forests, mosses and mushrooms, 5 km from the small town of Vetka.

All the residents of Vetka were evacuated at the end of April 1986, the city became like a ghost town: empty houses, closed shops, silence and emptiness. This is what Pripyat looks like now. However, at that time we traveled there by bicycles to look at the sights, like we were on an excursion. We climbed into abandoned orchards to eat apples and (whoever washed them?) rubbed them on a T-shirt – and put the fruit in our mouths.

There was so much we didn’t understand! Sediments of Iodine-131 and Cesium-137 were lying all around us. The epicentre was in this city. Cesium-137 is present there still today.

The important thing we had to remember is that we couldn’t go to the forest. Because the dosimeter crackled ominously even in a few meters away from it. The forest was a forbidden place all my childhood – from 6 to 18 years old. I never entered the forest; never even came close to it. I did not know the taste of mushrooms because they were forbidden to eat and still contain radioactive substances there. I don’t know how to search and pick mushrooms. I don’t know how to navigate in the woods and I can easily get lost there. The forest is an eternal source of radiation, because in that ecosystem it is poorly excreted.

With a dosimeter, we checked all root crops, vegetables and berries in the country. When it cracked, the vegetables were boiled in three consecutive pots of water: boiled – merged, boiled – merged, etc. Everything was washed and washed until the dosimeter calmed down.

We grew strange strawberries; the largest and most ridiculously shaped berries were given to me as a child. But these were mutant berries, fused or gigantic. I really thought that normal strawberries were the size of a palm, about 10 cm. Very often the berries grew to be gigantic and anomalous in shape. We marvelled as we ate them.

Iodine-131 quickly began to replace ordinary iodine in the thyroid gland of people, and pathologies began, including thyroid cancer. Everyone needed to take normal iodine for replacement. Iodine also prevented the accumulation of cesium and strontium in the body.

Red wine did not ‘remove’ radiation, but was a powerful antioxidant. That is, it suppressed the action of free radicals and inhibited the oxidative processes in the body that are triggered by radiation. In this sense, it can be considered a good preventive measure.

Eating of five walnuts a day protected against increased radiation. Walnuts increased resistance to high voltage X-rays.

Cesium-137: The most annoying thing about this radioisotope is its half-life of 30.17 years. Its positive characteristic is that it immediately forms compounds with oxygen; all its compounds are easily soluble and washed off with water. But it can accumulate in human tissues. It is quickly absorbed into the bloodstream, spreads throughout the body, and later can be concentrated in the lower section. Cesium-137 increases blood pressure, by constricting blood vessels, and causes sarcoma.

In Belarus, many of our population died from some form of cancer; my great-grandmother, the infectious disease specialist, died the same year. Later, my grandfather, who always lived near Vetka, contracted cancer. His wife, my grandmother, had problems with her thyroid gland all her life. Most young girls had miscarriages or stillbirths. And there were many such tragedies in my environment.

Animals were born with pathologies and quickly died. They say that spiders stopped spinning symmetrical webs and they produced something strange instead.

I appreciate everything adults have done for me: prohibition on going into the forest, washing food, including nuts, seaweed and red wine in the diet. Unfortunately, they were not able to control everything! So much information is easily assessed now, after almost 40 years. And now children are taught in school the mechanism of the accident, the way to stop a nuclear reactor and the causes of errors in the management of a nuclear power plant.

My child knows so much more about this than I did at her age.

It is so sad that we leave this problem, nuclear accident risk, to them and our future generations. They will have to make a new sarcophagus to cover this damaged facility and think about other forms of safe energy.

The Chernobyl accident is a tragic lesson for mankind.

III. GYPSY TABOR

Ah, romale, ah, chavale!

Ah, romale, ah, chavale!

Hey gypsies, hey guys.

Hey gypsies, hey guys.

Gypsy folk song

The threat of our area was a gypsy camp, through which it was necessary to go unnoticed to the local market. What seemed like easy questions – ‘How to get to the children’s clinic?’ or ‘What time is it?’ – left the defendant without money and in a state of hypnosis for the rest of the day.

The gypsies were professionals in their field, and they were also so traditional that they only needed a bear for a complete their entourage. Head scarves, long black braids, golden teeth, long layered skirts, shawls, hypnosis and palm reading, ‘predicting your fate in 5 minutes’, ‘complete diagnostics of your health in 3 minutes’. It was their ‘trade’.

On this ill-fated day, March 18, I had a birthday. I think I turned 11. Mum gave me 100 roubles for the purchase of products and sent me to the market and to the store. One hundred roubles in ten-rouble banknotes were rolled into a tube and neatly placed in a mitten held on with rubber bands. Yes, March in Siberia is as severe as the whole winter.

I walked along the ‘dangerous’ path, tightly clutching the pack of ten-rouble banknotes. And of course, the gypsy was already waiting for her prey around the corner. She simply asked, ‘What time is it?’ And she could not help but notice that the hand with the watch does not bend in the mitten. In gratitude for my answer, she said that she saw a curse and illness on me, which would certainly upset me right on my birthday. She confidently suggested to remove it immediately. Very quickly, the gypsy pulled three hairs out of the fringe of my hair and began to whisper something into them.

I watched carefully as I was ‘healed.’ At the end of the ritual, the gypsy suggested that I wrap my hair in any paper banknote and bury it in half-thawed earth. Hmm. I didn’t have small bills, and it was clearly difficult to get a ten-rouble note out of a rolled-up bundle. I hesitated.

But other gypsies began to surround us; a multi-coloured band with hooting, noise and uproar, which clearly put me into a stupor.

The gypsy quickly reached out for my mitten. At that moment, something happened, and I realised that the mitten was hanging on an elastic band, but there was no money in my palm. None. There was no money in the hands of the gypsy either. She blew on her empty palms like a good magician. She waved her hands in the air, as if dispersing the ‘evil eye and curse’ and announced that now I am completely healthy.

I stood completely shocked, feeling like a volunteer in a circus, who was pulled out of the auditorium by a magician. At the same time, I clearly realised that now there would be no salad, no lemonade, no cake with a cherry on my holiday table.

The gypsy band disappeared into space, as if it had never existed. I stood alone on the street. How?

It was all over. My holiday ended that moment. There were only two options left: go home and confess to Mum or …

…Go to the police! Where is our police?

Nearby was the metro station: ‘Karl Marks Square’. And it had a local police station. I ran there with tears shouting: ‘Help me, I was robbed!’

A tall policeman (like Mister Styopa in Marshak’s poem famous in my childhood) took my hand and asked who did it. I described the gypsy camp at the entrance to the subway. He frowned understandingly, called his partner, and they both went upstairs. There they caught the oldest gypsy from the whole camp; it was very upsetting for me, because she was not the one who robbed me. I even tried to tell the police that it was not the same woman. Because it seemed to me that the guilty should be punished, and not the oldest, who cannot quickly run away from the police.

But the policemen were professionals. They knew who to catch. We were taken to a room behind bars and the door was locked. The interrogation of the old gypsy began.

‘Get the money,’ they suggested to her in an amicable way. But the gypsy claimed that she had nothing.

‘Listen, we’re not going to lift up your skirts, come on!’ then I was surprised to learn that the skirts of gypsies are multi-layered.

Good and bad policemen took turns persuading and threatening the old caretaker of the camp.

I was sitting on a wooden bench opposite and watching it all, as if the second act of a circus performance was going on.

Finally, the gypsy gave up and began to lift one hem after another. The last skirt had a large pocket, from which the policeman began to get money and put it on the table in front of me. Crumpled banknotes of various denominations, my twisted ten-rouble notes – the full hem of the day’s earnings of the gypsy band was now on the table.

‘Is it your money?’ the policeman asked.

‘Mine,’ I replied. I happily looked at my tube of bills. And I didn’t claim anything else.

‘Take everything,’ the policeman commanded.

‘Everything!? Everything-everything?’ I didn’t believe what was happening.

But the policeman was already putting the money into a large bundle, which he handed to me.

‘Is it all for me?’ I asked in surprise.

The policeman grunted irritably and said: ‘March home, we don’t have time to mess around with you here, and don’t mess with the gypsies anymore!’

I signed some document, took the banknotes and put them in my pocket.

The old gypsy looked at me with her scary sparkling eyes, and I looked at her and slowly walked towards the exit. The duel with her eyes was like a telepathic dialogue, where she promised to meet me on the street once more, and I warned her not to dare to do this, otherwise it would end badly again.

I walked home, wondering if I had the right to take everything. Although, on the other hand, it was like a reward for the fact that I did not give up, did not get confused, was not afraid of gypsy magic and was able to solve my problem myself, without the help of my parents. I called the police myself; I signed the protocol myself. After all, it was like I had become a year older already!

A party that day was wonderful: with salads, lemonades, sweets and a cake with a cherry.

The terror of our area was a gypsy camp at the entrance to the market. The terror of the gypsy band was one 11-year-old girl, and no one ever touched her again.

IV. BIRDS OF PARADISE

In the cubicle behind the auditorium,

Rehearsed school band

Vocal-instrumental

Titled ‘Youth’.

Drummer, rhythm, lead and bass…

A song ‘Eternal youth’, ‘Chizh & Co’ band.

Gymnasium No. 10, with advanced studies of English, was famous throughout the city. City Olympiads in English have always been won by its students. The best running coach in the city brought up athletes who won prizes in all contests. But above all, the school was a source of creativity and self-expression. Each grade was famous for its rock band. At first, our idols were the Hot Punks and their red-haired drummer. On the walls, on the fences on the way to school, the red ‘Hot punks’ band logo was flaunted.

After them the ‘Anatomy of Soul’ headed by Ilya Sokolov appeared. By tradition, we called it in English ‘Anatomy of Soul’ because they sang in English. First the Nirvana songs; later, their own. Ilya was even more charismatic, more beautiful and broke the fragile hearts of girls. His rock band eventually became famous all around Russia.

I was a year younger than Ilya, we studied together at school, and after school we acted together in the same school theatre. I can confess that Ilya’s laurels did not give me peace and I also wanted to sing in a rock band, but they did not accept girls.

My dream came true at the beginning of the school year in the tenth grade, when we were divided into specialties. In my ‘medical’ class, girls with a musical education gathered. We were exactly five creative individuals who wanted to create a female rock band. This was our response to previous bands with their male machismo. There were no disputes between us, and each of us quickly decided who we would be in the group. So there was a drummer, bassist, keyboardist, solo guitarist and I became a lead singer.

Like all musicians, we automatically had pseudonyms: the drummer was ‘Stepashka’, the bassist was ‘Benya’, the keyboardist was ‘Khobotkova’ or ‘Fridge’, the solo guitarist was ‘Ermilchik’, and I was ‘Ushachkova’ or ‘Ushachok’. All these were derivatives of our surnames, which arose in a completely natural way in a creative environment.

Next came the external changes. Our solo guitarist dyed her hair ‘Green’, the bassist wove us so many baubles that each of us had both arms hung with them up to the elbow. I decided to pierce my ear, and make it a hallmark of my style. According to all the rules, an odd number of holes had to be pierced in the left ear. In general, there was enough space for only five. But even this was enough to ‘bring a heart attack’ to my parents. I remember how my mother sat down on a chair, paused for a long time, then asked for time to prepare my father. So, for a couple of weeks I lived with my hair down, covering my ears. However, the final idea of inserting five safety pins from large to small into the left ear betrayed me. My look definitely attracted attention, as everyone looked at my ear: some with admiration, some with surprise, and some with horror. But the main goal – for me to stand out – was certainly achieved. Then came ripped jeans, a lot of metal rings on the fingers and strange boots with thick soles.

Now we needed a title: shocking, controversial, and provocative. We decided to call ourselves a rock band ‘Bespredel’ (in Russian), but to make it even more mysterious, and so that only a select few could understand the true meaning, the name was translated into English – ‘Boundless’. I don’t know why we translated it this way, because we explained the meaning as ‘arbitrariness, lawlessness, self-will’, but it turned out somehow more poetically ‘boundless, endless’. Not surprisingly, everyone in our school liked this name, even teachers.

From that moment we started learning to play our instruments. Yes, it’s true, none of us knew how to drum or play the guitar before. We all studied at music schools in piano classes. Only the keyboardist was in perfect command of her instrument. Despite the fact that the first my idea was to be only a singer in the band, I found out that we lacked rhythm guitar. As a result, I also began to learn how to play acoustics, help therewith which I solicited from my mother at home.

We bought the first bass guitar from one punk for 100 roubles. To do this, we wove beaded baubles, which we handed over for sale to a tourist shop. The store sold them for 20 roubles and shared half of the proceeds. So, we earned 10 roubles from each bracelet, and very soon we bought the first guitar for our group.

We inherited the first drum kit from ‘Hot Punks’ and ‘Anatomy of the Soul’. We were advised to find a school sound engineer, Mister Kostya, who could provide help for our rehearsals.

Mister Kostya worked ‘In the cubicle behind the auditorium’. He was a tall, skinny man with large eyes and tousled hair. One fine day after school, five girls filled his cramped room with the news that we were a new rock-punk-girl band and we urgently needed him to open an auditorium for rehearsals, put a drum set on stage and connect a bass guitar to the speaker. Not a single muscle on his face trembled; he was not even surprised. Probably in all previous years, hearing the same demands from punky punks and hard rockers he had become immune. On the other hand, we were so sweet and harmless and could hardly cause any fear that we would break the drum or smash the guitar on the stage.

Mister Kostya even began to teach the drummer some basic rhythms and found an electric guitar for the solo guitarist. And what is most important, he opened the school auditorium for us, put the equipment on the stage, turned on the microphones, adjusted the volume and listened to our howl for as long as we rehearsed, never hinting that it was already late and his work day had ended.

Soon the parents of the keyboardist gave her a modern synthesizer that could imitate many sounds, which, of course, enriched our musical range or depth. And then the drummer’s parents bought her a drum kit at home, which took up a third of her room. From that moment we began to rehearse there. I don’t understand at all how the neighbours tolerated our work, but we rehearsed with a full sound. A little later, one of the familiar rock musicians gave me an electric guitar and I became a rhythm guitarist. Now we could be considered a full-fledged rock band.

We started rehearsing with the songs of Egor Letov, our Siberian punk: ‘Everything goes according to plan’ and ‘A fool walks through the forest’. And we had our own ideas on how to sing rock songs. We divided the music into three voices: the keyboardist, the bassist and I. We had three different timbres – soprano, mezzo-soprano and contralto. Our songs took on in their own unique style: female polyphonic rock. Each subsequent song was now sorted by voices. Next, we played the songs of the groups: Chizh&Co, Chaif, DDT and Nautilus Pompilius. Finally, inspired by success, we started writing our own lyrics and tunes. As a result, our own repertoire began to expand and enrich itself. The bass player was the most productive. She wrote many songs that entered our repertoire. I also wrote songs, sometimes even on the verses of the classics, and I liked gothic rock.

For one concert we sewed long dark cloaks with big hoods to hide our faces. In the semi-darkness, we went on stage in such attire; the bass began a solo, then I pulled the bass strings on my electric guitar and pressed the distortion pedal. We enjoyed this wonderful powerful sound and sang a song with voices beyond the grave to the words of Nikolai Gumilyov, which, like no other, conveyed Gothic style:

I dreamt that we both died together,

Lay calm and our eyes nothing bothers,

Two coffins stand whiter than ever

Alongside each other.

What time did we say ‘it’s all over’?

And what does it mean all these years?

It’s strange, but my heart doesn’t bother,

My heart has no tears.

Disempowered feelings so weird,

And all frozen thoughts are so clear,

My need for your lips disappeared

Though they are so near.

It happened: we both died together,

Lay calm and our eyes nothing bothers,

Two coffins stand whiter than ever

Alongside each other.

The concert was a success. We even had a fan club from the lower grades; they went to our rehearsals in the auditorium or tagged along on breaks.

Together with the repertoire, our fame in musical circles increased. As a result, we moved to rehearse in the Cultural Centre next to the school, and found a producer – Oleg Borisovich. He was a long-haired rocker, always dressed in jeans and a denim jacket regardless of the season. He was the coolest and most famous sound engineer in our city. Therefore, he organised concerts for popular bands and performers. Thanks to him, we constantly attended concerts of rock stars. He began to promote us in the musical circles of the city. By the summer we had reached such a high level that we were invited to sing at a summer rock festival.

A large stage was always installed in the central square of the city for this festival, and the groups, one after another, performed all day long. The central street was blocked and became pedestrian-only from the Ob River to the centre of the city. People flocked to the square near the stage to enjoy socialising, rock music and to jump around, shaking their heads.

When it was our turn to perform, the host of the concert forgot our band’s name in English – ‘Boundless’. Moreover, he did not know its Russian translation. Therefore, improvising, he shouted into the microphone loudly: ‘Meet Rock group ‘‘Birds of Paradise’’!’

What? What did he say? How dare he call us such an idiotic name? The crowd picked up the idea, and we heard a whistle and drunken spectators yelled: ‘Hens of Paradise! Come on! Quail! Chickens!’

What a blow to our ego. For the first time someone did not take us seriously; did not understand that women can also organise a rock band. At the age 16 we were adults and they whistled to us like we were children. How dare they do that! Despite this, the group performed, but with a heavy heart and girls went home with a deflated faith in themselves.

Less inspired, we kept rehearsing. Once after rehearsal, we were walking home late in the evening with guitars on our backs and went into a small convenience store to buy bread. Having paid for the bread, we went to the exit, but a large company of guys older and taller than us blocked the doors. They surrounded us in a ring, and it looked like we would not leave alive. At first, I thought they were going to rob us and I recalled how much money I had left in my wallet. The cockiest guy stepped forward and said, ‘Are you the ‘Birds of Paradise’? ’ At this point, we all turned pale, our legs became wobbly, and we nearly swallowed our tongues. They had recognised us!

During the ’90s in our country, the class of ‘gopniks’ (members of a delinquent subculture in former Soviet republics – young people of working-class background who usually live in suburban areas and come from a family of poor education and income) actively attacked the class of ‘informals’, to which we belonged. Fights between these two classes were common and, as a rule, the ‘gopniks’ won. First, because they always gathered in large groups and, second, they considered themselves ‘real guys’ and had connections; more ‘goodfellas’ from the district joined them at one whistle. So the ‘informals’ had no chance against them.

We were standing surrounded by these guys, already clearly imagining how we would be beaten, automatically covering our chest and stomach with our hands. I even tried to predict when they would start beating us, right in the store or let us go outside? The seller could have called the police, but before they could arrive, I imagined that we would be writhing on the lawn. Finally, I thought that torment should be accepted proudly, and I confidently said: ‘Yes, we are the “Birds of Paradise band!” What’s wrong with me? What birds? We were the ‘Boundless’ band, weren’t we?!

Unexpectedly for us, the guys perked up, broke into a smile, and began to look at us with some kind of genuine admiration. The leader of the gang began to look in his pockets for either a pen or a piece of paper. ‘Girls, give us your autographs, please!’ They started to say in so many words that they were our fans, that they liked us and that they were extremely happy to meet us personally. As a result, pens and some pieces of paper were found, and we began to leave our autographs.

To Vasya with love from the band ‘Birds of Paradise’

I wrote it on a piece of paper, and thought that at this moment we accepted the new name of our band. From this evening until the end of our career as a band, we were the ‘Birds of Paradise’ band. After all, people in the city remembered us under this name. We were recognised on the street under this name. Wasn’t this the establishment of our fame?

We flew back home on wings of excitement. We were now a female rock band well-known in the city, with a beautiful name that no one would ever confuse.

In the 11th grade, we entered the preparatory courses at the Medical Institute, where we went after rehearsals with guitars behind our backs. Classes were held in the main building, where the administration was located. Then the dean of the medical faculty, Ganin Anatoly Fedorovich, became aware of us. He was a creative person and always organised concerts and KVNs at the Institute. We were immediately invited to perform for them. Anatoly Fedorovich became our next patron.

Nothing could have been better than this acquaintance and his support. Our fate was predetermined: the Faculty of Medicine was waiting for us. In April, at the end of the academic year, we passed the exams of the preparatory courses, and were already ‘accepted’ to the Medical Institute, having not yet finished school. We can say that our musical career paved the way for us to the career of doctors, even predetermined our specialisation. The Medical Faculty and Ganin would not have given us to anyone else.

Four of us began to study at the Medical Institute. The band continued to play and we maintained our informal image.

* * *

I remember how the first cycle of ‘therapeutic diseases’ began in the hospital, and we – medical students – were sent to observe the real patients in the wards. Feeling almost like doctors, we spread out around the department. I went to my patient and sat down opposite her, crossing my legs. The knee was bare in torn jeans, a boot with a large sole hung in the air, baubles with the names of rock bands fell on the wrist, making it difficult to write a medical history and pins flaunted in the ear. The patient looked at me in a strange way and struggled to answer my questions. However, I got used to such a reaction, even perceived it as attention to my person. I am a rock star!

After that clinical experience, I returned to the staff room to continue filling out the patient’s history and prescribing medications. At that moment, the door opened slightly and a woman appeared in it. She asked for the head of the department. The doctor raised her head and asked her what she wanted. The patient hesitated a little and plaintively asked: ‘Excuse me, but can I replace the doctor?’ Now we all looked at the woman with interest. To my surprise, this was my patient.

‘What’s wrong with your doctor?’ the head of department asked irritably.

‘I don’t trust her,’ the patient explained uncertainly.

‘Who is your doctor?’ and the head of department began to look attentively into the faces of us medical students. I met her eyes. I was betrayed by red cheeks, baubles, torn jeans, and ‘damn what’ in my left ear. She looked at my entourage for a while and pondered.

‘We will replace the doctor for you. You may go now,’ she promised to the patient.

The door quietly closed, the doctor looked at me again and briefly said: ‘Come in normal clothes tomorrow and remove the pins from your ear.’

A compromise seems to have been found. Indeed, since then, we have kept a certain dress code for seeing patients, which by default remains the image of a doctor. Since then, I have five neat earrings instead of pins, and the number of bracelets has decreased significantly. The rock group existed until the end of our studies at the Medical Institute. Then work, night shifts, families and children began, and music simply faded into the background, fulfilling an important role in our lives as creative self-realisation. I love our time as ‘Birds of Paradise’.

V. REQUIEM FOR HIM

Lacrimosa dies illa

Qua resurget ex favilla

Judicandus homo reus.

Huic ergo parce, Deus:

Pie Jesu Domine,

Dona eis requiem. Amen

Full of tears that day

When the man rises from the ashes

To be condemned.

So have mercy on him, God

Merciful Lord Jesus,

Grant them peace. Amen

Requiem, Lacrimosa, V.A. Mozart

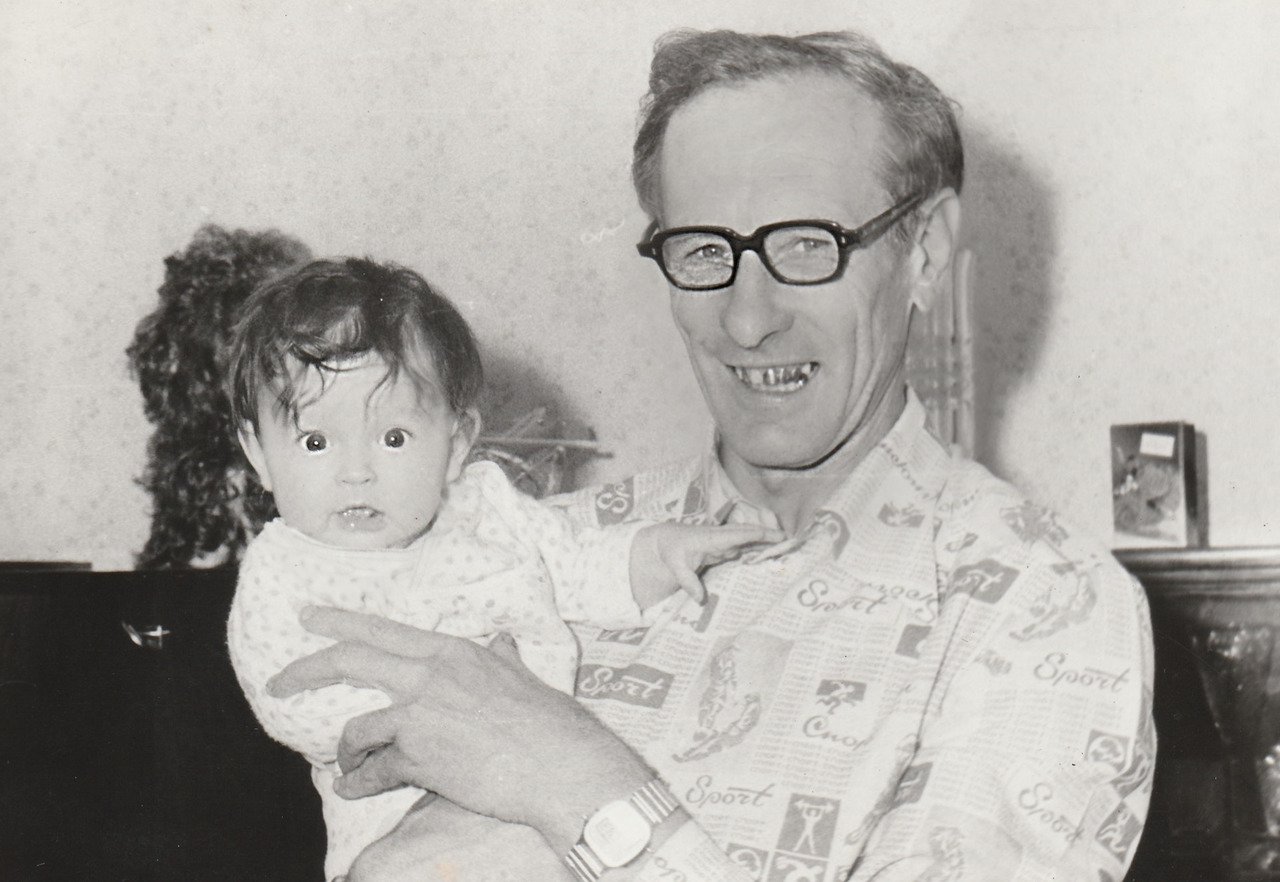

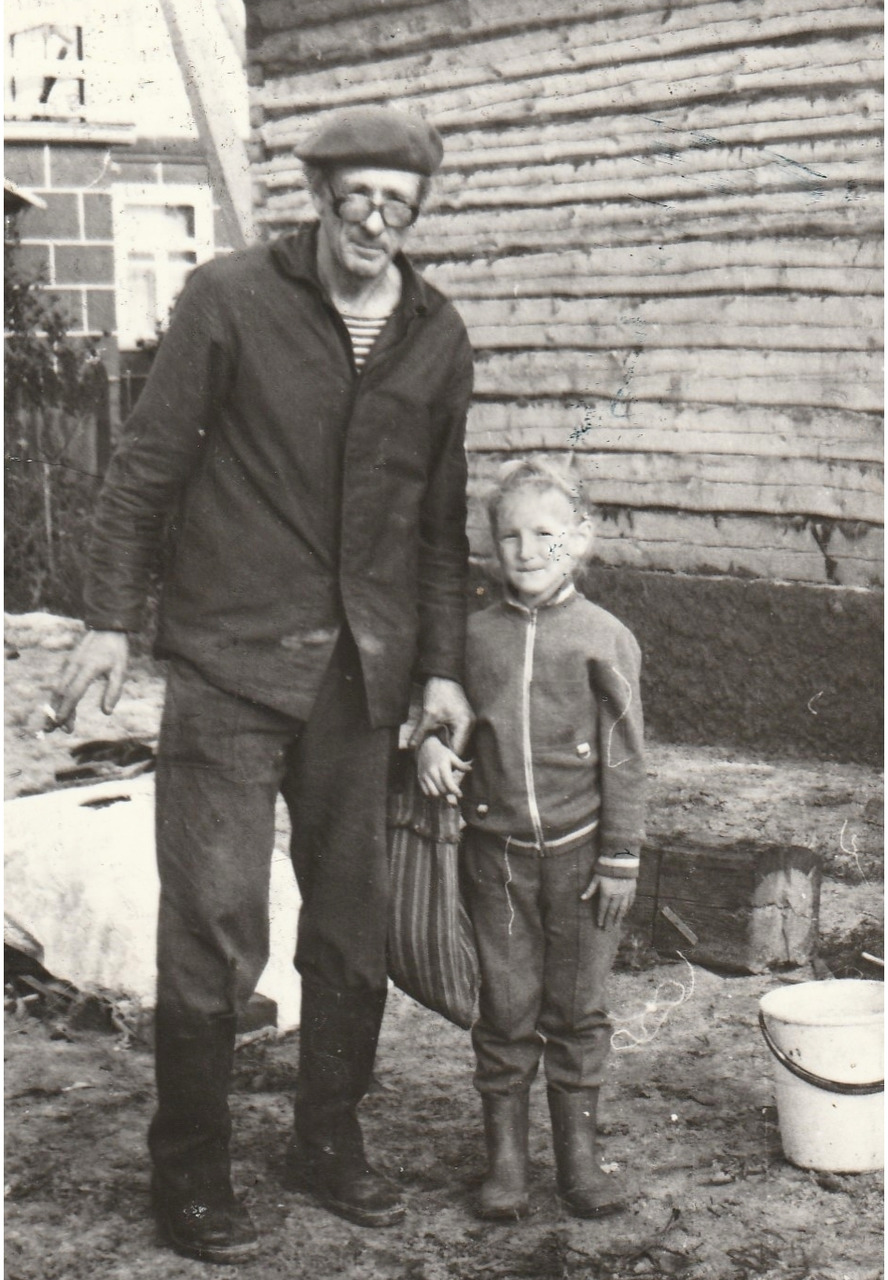

My grandfather Georgy Grigoriyevich Koltsov – the son of Nadezhda Alexandrovna Koltsova and Grigoriy Vasilevich Koltsov played a great role in choosing my profession.

He always wanted me to become a doctor. And he was a HEALER.

He taught me how to collect herbs, dry, store and use them. He had a thick handwritten notebook with recipes and herbal names. He could prepare any healing concoction. He knew how to treat almost all illnesses with herbal tinctures.

I spent the summer with him in the countryside. My grandfather woke me up at the first light of the sun. We looked for half-blown calendula buds, cut them off and dried them in the attic. In the afternoon we walked through the fields and looked for a young yellow immortelle. Immortelle brooms were dried on slats under the roof. We picked tansy in the meadow. As a child, I believed that these were daisies that had lost their petals. Medicinal chamomiles were a must in our collection. And fragrant thyme, dill, coriander, mint, lemon balm, and lemongrass – everything grew in the garden near the house.

My grandfather knew how to make chemical solutions to protect plants from diseases and pests. His ‘laboratory’ contained pouches, jars, and boxes of multi-coloured powders and crystals. At that time, I believed that alchemists and the Philosopher’s Stone existed.

I learned everything from him. The most interesting part was mixing solutions and powders. Several times I confused the correct proportions of the preparations and I had severe poisoning, after which he had to bring me back to life. Since than I always remember how important is to follow the protocols strictly.

Once I carelessly ate berries from a bush, which he treated with copper sulphate. In the forensic toxicology literature, copper preparations are usually classified as destructive poisons by their action; this property of such poisons is sharply manifested in changes in the liver and kidneys. In case of poisoning with copper sulphate, the death of erythrocytes occurs, which is typical for the action of haemolytic poisons. Such syndromes result in destruction of red blood cells, anaemia, jaundice, and hemosiderin deposits in the liver, spleen, and kidneys. My condition was severe. But he found a way to heal me again.

But one day he felt ill. Doctors diagnosed bladder cancer. Despite the operation, metastases went to the pubic bone. Only chemotherapy and radiotherapy could be used for treatment. The doctors said that he had a couple of months left to live.

But he found a great herbal regimen and started using it. This phyto-protocol extended his life by as much as 11 years, despite the doctors’ verdict. Every year during these years he took a course of herbal tinctures and continued to live.

Subsequently, we gave this scheme to many people with cancer. And it has extended life for most of them.

At that critical moment in his life, when he was first diagnosed with cancer, he began to listen to classical music. Most of all he loved Mozart’s Requiem. He had an old record player. I remember that big black vinyl record. And I even knew on what division ‘Lacrimosa’ begins in the Requiem. We loved listening to this part together. I even sang:

Lacrimosa dies illa

Qua resurget ex favilla

Judicandus homo reus.

Huic ergo parce, Deus:

Pie Jesu Domine,

Dona eis requiem. Amen.

Nine years from that moment, I bought him a CD disc ‘Requiem’ by Mozart and I became a doctor and scientist.

It seemed to us that we had conquered the disease.

But one day he became ill, he felt weakness and pain in his legs. We called an ambulance. Paramedics immediately took him to surgery. They seemed to suspect vein thrombosis. I followed the ambulance in my car, looking at the closed rear doors with red crosses. I was afraid to lag too far behind; we flew through traffic lights and intersections. I was afraid to lose sight of those doors.

We arrived at an old hospital on the outskirts of the city. There were many hours of examinations and consultations. Finally, we were allowed to go home and were given a referral to an oncologist.

The next day we were at the reception at the regional oncology centre. The doctor made a puncture of the lymph nodes and sent it to the laboratory for diagnosis.

After that, the oncologist called me into the office, alone. I remember that doctor suggested that grandfather look at the museum of stones removed after urolithiasis, and then doctor pulled me by the hand into the staff room.

‘These are his last two weeks,’ the doctor said.

‘What?’ I asked as if I did not hear.

‘These are the last two weeks of his life.’

‘What do you mean?’ I mumbled, as if those words were supposed to have a different meaning.

‘We can’t help him.’

‘Why do you say NOTHING? What about the operation?’

‘Technically it is not possible. These are multiple metastases that thrombose the veins.’

‘Radiotherapy?’

‘He has already received the maximum dose; no more radiation can be given.’

‘Chemotherapy?’

‘Let me explain: even if we extend his life for another two weeks, he will spend this period in terrible intoxication, weakness and depression. Do you wish him such a state?’

‘No!!!’ I objected. ‘But what can we do for him?’

‘Make the last two weeks of his life as happy as possible.’

Our conversation was, of course, longer. Of course, I argued with the oncologist, suggesting many more methods of treatment. But his answer boiled down to one ‘MAKE THE LAST DAYS OF HIS LIFE AS HAPPY AS POSSIBLE!’

And of course, I didn’t want to believe it was the last two weeks. But I knew it. So it was my personal hell. Do you know where it is? It is somewhere between brain and heart. It’s what you feel and what you think. You find yourself in hell, and it’s really bad there.

…I left the staff room, found my grandfather in the museum, and we went to the car. In silence we sat down. A lump stuck in my throat; it caused physical pain and did not even allow me to swallow or speak.

He silently took the Requiem CD from the glove compartment of the car. And turned it on. He turned the volume up to the maximum, opened windows of the car and asked me to drive at the maximum speed allowed. Damn Lacrimosa, damn Mozart. How did he know that the violin saws the brain so thinly and sharply. I was dying with every sound for every next day.

Lacrimosa dies illa

Qua resurget ex favilla

Judicandus homo reus…

We didn’t talk about anything, we were silent, and I tried to guess in his silence whether he understood why I was silent?

After all, I didn’t tell anyone that we had two weeks. Because I didn’t want to share this pain with anyone. Because it was important for me that during these two weeks everyone around was happy. He didn’t ask me either, I still don’t know if he knew it was the end.

It was a wonderful, sunny, joyful summer. And the last two weeks had been the most intense. We travelled, did what we wanted, bought what we wanted, ate and drank what we wanted. Only I tore off calendar sheets 9, 8, 7, 6…1. It was the last day. He called me to inform that he changed the tariff plan and added me as a ‘friend’, and now we can talk on the phone for free and unlimited.

He died exactly 30 minutes later, because of thromboembolism of the lungs. Immediate death. Exactly in 2 weeks, as the oncologist said. Exactly in 14 days according to my calendar.

A day later, my phone rang. I sat in my car and looked in surprise at the screen where his name was displayed. I knew for sure it was him, so I picked up the phone: ‘Hello?’

There was some sort of noise coming from the other end.

‘Hello? I’m listening you,’ I repeated.

The sound, like a radio wave, continued, creaking, thumping and whistling. I listened as if I might make out something. Something important that we hadn’t agreed on. And suddenly I realised!

‘I will always remember you … Do you want me to play a ‘‘Requiem’’ for you?’ and I turned on the music. We raced in the car with the windows open with him and Mozart again. Like that day. LACRIMOSA. REQUIEM FOR HIM. IN MEMORY OF HIM. ‘Merciful Lord Jesus, grant him peace. Amen.’

VI. HOW I BECAME A VIROLOGIST

Scio me nihil scire

Socrates

After graduating from medical university, I entered an internship in infectious diseases. Only four of the 300 students of our medical faculty chose this direction. We all found ourselves in an interesting place where the clinic and the research institute were located on the same territory and worked closely with each other.

One intern had been working in the virology laboratory since summer. He regularly entertained us with exciting stories from the field of science on the way to the hospital and back.

We spent two hours on the road every day, so the stories turned into heated discussions. So, I learned how viruses were grown, how they were sequenced, how new ones were discovered. He told me about the creation of vaccines, genetic engineering and molecular biology. All this was a hitherto unknown world.

Eventually I wanted to work in the same laboratory as he did. I went to the personnel department of the research institute, wrote an application with a request to take me as a laboratory assistant and left my resume (British – curriculum vitae).

A few days later, the Deputy Director of Scientific work called me and asked why I wanted to work in the laboratory. I passionately described how interesting it would be for me to work in science, even though I had not a single day of experience.

‘We can’t hire you as a laboratory assistant,’ he answered.

‘Why? Maybe I can wash the dishes or clean up in the laboratory? Please, give me any task!’

‘No,’ was his reply. ‘But you can do research on virology in a postgraduate course.’

Suddenly everything turned upside down. To enter a graduate school in virology and take an entrance exam was not a part of my plans at all. But our intern – the one who had been entertaining us with stories of virology – was overjoyed at the news. He was just going to study in graduate school and was seriously preparing for that. Now he persuaded me to go with him and promised that he would prompt and help during the exam. I even bought a book from the category ‘Entertaining Virology’ on his advice.

That summer I remembered that I needed to read ‘Entertaining Virology’ from time to time. So I had finished reading it only by September. Actually, I hoped to shift the responsibility to my friend for his help. He was so smart, well-read and responsible that I could really rely on him. But his phone didn’t answer. Big deal! Probably he had changed his number.

Autumn had begun. An exam date had been set. I came to the institute in the morning and found myself standing alone in the corridor. I had been waiting for 10–15 minutes, and then I started to get nervous. No one else came, nothing happened, and my comrade was absent. I went to the office where the exam was to be held and opened the door. Four serious men were sitting at a long table. And on the right, at a separate table, a small, sweet, fair-haired woman was sitting.

‘Good morning. Where is everyone?’ I asked confused. Nothing more stupid could be said, indeed.

‘The entire commission is here. We are waiting for you,’ the woman replied smiling.

‘I’ll wait for another person to come and we’ll go in together,’ was my response.

‘Lady, you are the only one registered for the exam, come in, we are waiting for you,’ a deep voice of the chairman of the selection committee sounded.

A shiver ran through my body and sweat broke out. ‘Alone at the exam? Where is my friend? Who will help me?’ Definitely it felt like my time to get out from the upcoming shame.

I blurted out: ‘Sorry, I won’t take the exam, goodbye!’ and closed the door.

I made my way towards the hall and down the stairs with a firm resolve to end the ridiculous situation as soon as possible. I even managed to go one stairway down.

‘Stop!!! Freeze!!!’ I heard. ‘Where are you going?’

That nice woman was standing upstairs and looking at me severely.

‘I’m going home. You see, I don’t know virology very well, I’m not sure I can pass the exam.’

‘What do you think?! Such a commission of four professors gathered for you alone, and you just want to leave?’ she stated strongly.

She pulled me back, taking my hand as if I was a child.

‘Nooo. Please, let me go, I don’t know anything, I can’t…’ I begged her. What a terrible moment of shame and disgrace.

‘You will have time to prepare,’ the woman promised me. ‘Everything will be fine.’

She literally pushed me back into the auditorium and solemnly invited me to choose an exam paper with questions for virology.

I felt the complete hopelessness of the moment. My attempt to escape had failed, and now all eyes were on me. There was nowhere to retreat. With a trembling hand, I reached for one exam paper with questions, then changed my mind and reached for another, straining my psychic abilities to choose the lightest of them. Rather, it was a deception of consciousness, an illusion of choice.

As I recall now, the topic of West Nile Fever was the most important of the three topics in my exam paper. Eventually, this virus will become an interest of mine, but at that moment it caused only a strong trembling.

The secretary suggested that I sit at the table with a pen and paper. There was an absolute silence in which I tried to pretend that I already knew what to write about. My pen was busily scribbling the name of the fever on the paper. I even guessed that it is found in Egypt, on the Nile River, and most likely it is carried by mosquitoes. It remained to compose the symptoms. Without a doubt, with all viral infections, there is fever, intoxication, body pain, what else? …

At the most difficult moment of my reflections, the nice woman got up from her seat and approached the professors. Leaning over them, she softly invited them to drink tea in another office, then she turned her head towards me and winked meaningfully. Now I had a ‘chance’ to pass the exam. The main thing was to find the answers in the book quickly, memorize them and present them beautifully.

Still, I was tormented by the question, where was my colleague and why was I sitting alone at the exam. And why only one person out of 300 people from the ‘Medicine Faculty’ of the Medical Institute and 400 people from the ‘Faculty of Natural Sciences’ of Novosibirsk State University, came to enter the graduate school in virology? There must be some mistake?

The commission returned and began to torture me with pleasure. I remembered what I could, and regretted that we absolutely did not devote time to virology in the medical institute. It was part of microbiology, but there were enough bacteria to fill the entire course with them. And as for viruses, we learned well only influenza, parainfluenza, adenovirus, rhinovirus and viral hepatitis.

The strange science of virology had been discovered by me only a year before. And its rise came in the ’60s of the twentieth century, and, with the development of the success of vaccination, the epidemics of viral diseases began to fade. Poliovirus and smallpox stopped circulating. And it seemed, why should I learn about these viruses if I would no longer meet them in practice? Also in the 60s, many antiviral drugs were invented, and it seemed that there was nothing more to do in this science. Everything had already been studied.

The exam ended successfully. As a result, I got a 4 (out of 5 – in Russia there is 5-point rating system), not bad for the current situation, and was admitted to the postgraduate program in virology in the department of Flaviviruses and Viral Hepatitis. And my supervisor was the same Deputy Director of Scientific work.

From that moment on, my life changed direction forever. Thanks to my missing comrade, thanks to the secretary of the commission that stopped me, thanks to my supervisor who loved virology.

As I found out a little later, our intern was married that summer to a girl whose parents had a large car company, and they persuaded him to join their business. So he gave up the idea of going to graduate school and even the idea of being a doctor.

The other two interns started their careers in the pharmaceutical business.

As for me, I worked in the infectious diseases hospital, and in the evenings I conducted scientific research in the very laboratory in which I dreamed to work so much.

Seems like it was fate.

VII. EBOLA. THE SEAMY SIDE OF A PROFESSION

May 5, 2004

I am an intern doctor in the emergency room of the Regional Centre for AIDS and Especially Dangerous Infections. Young, dreaming and brave. I wanted to save people from the most terrible infections in the world.

I finished writing a patient‘s medical history and made a cup of tea.

On this very day, Antonina Presnyakova, a laboratory assistant, underwent a briefing and a medical examination at the State Research Centre of Virology and Biotechnology “Vector” and then proceeded to inject experimental guinea pigs infected with the Ebola virus. Having finished the experiment, Antonina began to put a cap on the needle of the syringe, and at that moment her hand trembled. The needle pierced two pairs of rubber gloves and then pierced the skin on her left palm.

As a result, she was infected with the Ebola haemorrhagic fever. Despite ongoing therapy, May 19, 2004 the patient died. She was 46 years old.

Even then, the Ebola news came upon the world with a shock. The Ebola virus was first identified in the equatorial province of Sudan and adjacent areas of Zaire in 1976. The virus was isolated in the Ebola River region. This gave the virus its name.

The virus was spread through direct contact with bodily fluids, such as blood, from infected people or animals. Its spread could also occur by contact with items recently contaminated with bodily fluids.

Death usually occurred in the second week of illness as a result of massive bleeding and shock. The maximum lethality was 90%.

After Antonina’s hospitalisation, we admitted three people who had contact with her after her exposure. I carefully examined everyone and recorded their case histories. We put everyone in special Meltzer boxes for observation.

By Friday, it became clear that Antonina was suffering from Ebola. Everything was complicated by the fact that two of the other three also had a temperature rise to 38.0–39.0⁰С.

I left work in а panic, thinking that I also had been in contact with them. I clearly knew the symptoms of Ebola: fatigue, weakness, loss of appetite and headache. It seemed that they had already begun for me.

I’d been holding on emotionally until I arrived at home and the front door closed behind me. At that moment, a cry broke out of me into space: ‘I don’t want to die, I don’t waaaaant tooooo die.’ I collapsed onto the bed, buried my face in the pillow, and began to sob.

I roared, having a full understanding of how everything could develop and realising the drama of what was happening. After all, I had just started working as an infectious disease doctor, and I felt so sorry for myself, so scared, so insulted that everything could end now. Then I thought about the fragility of human life, how difficult it is to gain and how easy it is to lose. I literally screamed into space: ‘I don’t want to die!!!’

After two days of sobbing over the weekend, I returned to work. Our resuscitator stayed with Antonina. He was supposed to spend the whole time with her until recovery or death, plus the incubation period from the last day of contact. He did not return home that day. And the family would only see him in 2–3 months later.

Antonina left for work on the morning of May 5, 2004, and none of her relatives saw her again. She was buried according to special rules: in a sealed zinc coffin, covered with chlorine powder. The grave was twice as deep, and it was filled with concrete from above, so that it would not be dug up or washed away by a flood. Her family had no possibility to say goodbye to her.

Бесплатный фрагмент закончился.

Купите книгу, чтобы продолжить чтение.