Бесплатный фрагмент - Ecosociology Sources

Series: «Ecosociology»

About ecosociology and ecosociologists

The concept of “ecosociology” and ecosociology as a science was formed in the inter-disciplinary area of social and natural sciences. It is closely related to environmentalism, the basic concepts of which were introduced to sociology in the 19th century. In the 20th century, these basic concepts were developed within the framework of the environmental sociological theory. In the 21st century, they became widely accepted in sociology with the emergence of the profession of an ecosociologists.

1992 marked the final institutionalization of environmental sociology in the world as the International Sociological Association established the Research Committee “Environment and Society” (RC-24), which actively worked today and from 2015, started publishing its own international peer-reviewed scientific journal “Environmental Sociology”.

In 1998, the Russian Society of Sociologists formed a Research Committee for “Ecosociology”, which actively participates in thematic sociological events, promotes addressing research and applied scientific tasks, the transfer of eco-sociological knowledge to students and across inter-disciplinary areas.

Environmentalism is simultaneously an ideology and an area of expertise oriented to understanding and studying the interaction between humans and nature, as well as hands-on application of such expertise.

Ecosociology is the science studying the patterns of functioning, development and interaction of the social and natural environments.

In Russia, the debate about the “correct” Russian-language title for environmental sociology is still ongoing. The point is that the social and mental attitudes held by environmentalists and ecologists are somewhat different. Environmentalists are sometimes also called deep ecologists, as, in their opinion, the domain of discourse and learning should include the ecology of consciousness, soul and spirit.

In fact, the Russian texts and discourses use as synonyms two notions and scientific discipline titles — social ecology and environmental sociology (eco-sociology, ecosociology). These are now only a step away from becoming independent disciplines. This difference should be clarified and the division process should be ended.

Social ecology, also referred to as human ecology or ecology of human existence, elaborates the scientific foundation for analysis of vital activities and governance of socio-ecological systems, norms and regulations relating to natural resource use, labor protection and human health, sanitation and hygiene, environmental impact assessment, regulations for environmental impact audits, guidance manuals, engineering and technological solutions.

Social ecology is a complex of all areas of expertise shaped to ensure an optimal interaction of the social and natural environments.

Social ecology is the domain of experts specializing in ecology, biology, management, sanitation and hygiene, engineering and so on, as well as sociologists, philosophers, psychologists, pedagogues and other humanitarians. Social ecologists, using the techniques of their profession, identify an efficient method and the shortest way for overcoming risks, harmonization of the social medium and the natural environment.

In the same manner, ecosociology is studied by people representing many professions from diverse fields of science. They address the same task using sociological methods. Therefore, in the scheme suggested, the place of ecosociology can be taken by any discipline prefixed with “eco”.

For ecosociologists, the natural environment is the permanent context of the interpersonal relations being studied. They study practical interaction with nature and discourse relating to nature, environmental awareness and values, environmentalism as a social movement for better quality of environmental conditions and theoretical reflection of a large number of authors from diverse fields of science, politics and production.

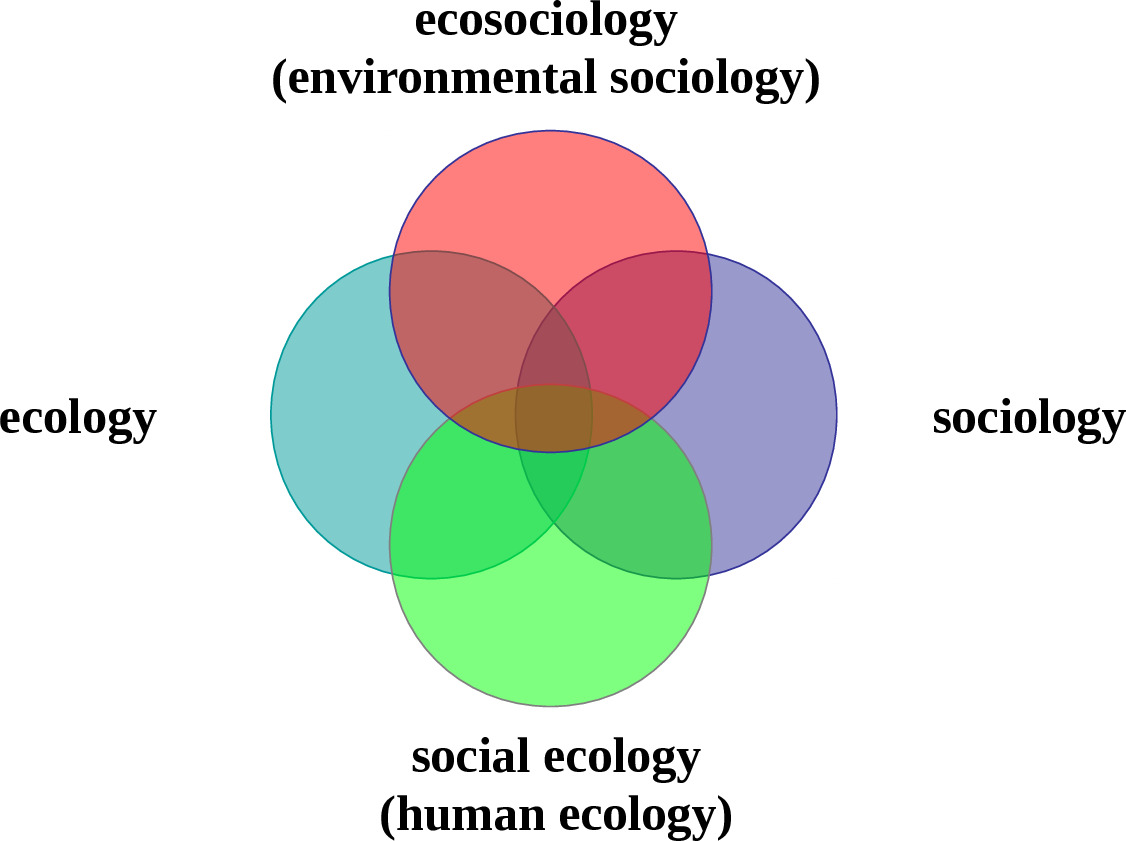

Ecosociology is a subdivision within sociology, social ecology and ecology. This understanding is analogous to the structure of the socio-ecological complex. It clearly highlights the difference between ecosociology and social ecology as well as that between ecosociologists and scholars from other fields of science.

If a philosopher or political scientist analyzes data from his field of science, including and verifying conclusions with sociological data obtained by himself or his peers using sociological techniques in the course of sociological research, writes about the interaction between the human and the environment, can we call this person an ecosociologist? On the other hand, take a publication in the international journal Environmental Policy elaborating on interaction between society and nature and coauthored by a geographer, a biologist, an economist, a physician and a publicist who gathered materials for this article using qualitative sociological techniques. Can these publications be placed in the library section titled Ecosociology? Or will it be more appropriate to place them in the Social Ecology section? Does that mean that the boundary between ecosociology and social ecology will remain blurred by their inter-disciplinary nature, combining of professions and co-authorship?

The answer would be: a person is an ecosociologist if he complies with the three principles of identity:

1) In his research, he uses sociological techniques and his analysis relies upon sociological theories. The context of the research relates to the social and natural environment. The object of research are social structures and institutes, organizations and communities, groups and individuals who interact with nature and with each other on the subject of nature. The subject of the research is the social aspects and mechanisms of various participants of this interaction, their causes and consequences, development stages and examples.

2) This person is referred to as an ecosociologist by peers and authors.

3) This person refers to himself / herself as an ecosociologist.

Foreword

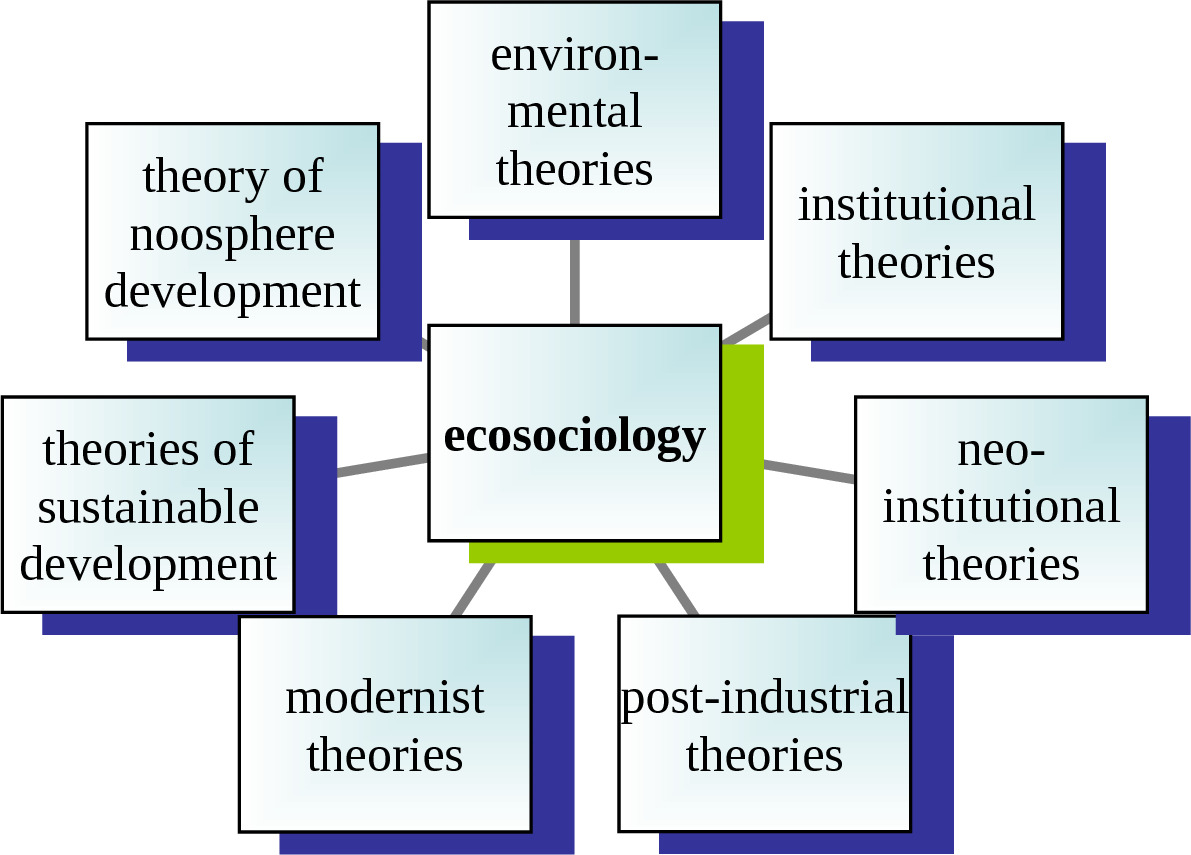

Ecosociology sources are contained in institutional, neo-institutional, post-industrial and modernist theories, which were developing all over the world, including Russia. This found its reflection in the theories of sustainable development and noosphere genesis.

The main source making possible the emergence, establishment and development of ecosociology relates to inter-disciplinary environmental (socio-ecological) theories. They analyze various aspects of interaction between humans and nature, society and the environment.

Environmental theories

Introduction

Environmental theories became the first and most important theoretical source of ecosociology. While these theories are quite diverse, they, as a whole, have shaped environmentalism into a scientific-practical concept and a focal area of public ecological movement. In its evolution, environmentalism was influenced by the emergence and development of naturalism and ecologism, each consisting of many socio-ecological theories and concepts, scientific schools and lines of research.

Sociological naturalism

Naturalism in sociology is inherent to theories that explain social development, interaction and phenomena by various natural factors — geographical and climatic conditions, features of the landscape, flora and fauna, biological and racial aspects of human nature. To explain social phenomena and processes, naturalists used methods of natural sciences. In the mid-19th — early 20th century, naturalism in sociology was devoted into social biologism and social mechanicism.

Social biologism proceeds on the basis that social phenomena and laws of the society’s functioning and development are analogous to biological laws, and that they can be studied using biological sciences and their methods. It comprises the concepts of social evolutionism and social Darwinism, which will be considered in more detail below. Social mechanicism, while sharing this view, prefers using physical sciences and their methods.

Representatives of both schools are correct in their own fashion, as they appeal to nature, its phenomena and laws. However, with the continuing development of sociology and its own methods in the second half of the 20th century and ever since, naturalists have tried to absorb criticism and new empirical data to elaborate two main approaches — ontological and methodological. Both are based on the understanding that science is universal and the world is cognizable.

The supporters of ontological naturalism are positive that things social can be narrowed down to things physical, and that all explanations about the social environment or behavior of an individual can be found within the framework of natural sciences. In the social process, they see only physiological characteristics and physical substances (substantialism). For example, this view is now quite typical for geneticists, biochemists and neurobiologists. In sociology, this trend is represented by behavioral sociology and biosociology.

Those who advocate methodological naturalism are positive that the social sphere has its own, unique features. However, natural-science techniques are sufficient for obtaining knowledge about the social sphere (reductionism) and for linking it with the knowledge about the biotic and abiotic spheres. Among sociological theories, this approach is typical for structural functionalism and neo-evolutionism, theories of system analysis, social exchange and other theories.

Despite the apparent contradiction, one can see that these two approaches in naturalism, as well as modern achievements of natural and social sciences, complement each other. Therefore, we will continue our search for the sources of ecosociology, which is, in fact, inter-disciplinary.

Social evolutionism

Social evolutionism was founded by Herbert Spencer (1820—1903). Spencer proposed and justified the theory of social evolution before the emergence of Darwin’s theory of biological evolution. Spencer was developing sociology as a natural science. His theory of society is based on the evolution theory, in particular, the idea of organic development and struggle for existence. Spencer believed that the organic world developed from the non-organic one, and that humans and society are a product of the organic world (organic school). He proposed his understanding of the universal evolution law — the energy conservation law applying both to nature and to society. He used this law for deriving social development trends.

Albert Eberhard Friedrich Schaffle (1831—1903), who viewed society as an organism, also made a large contribution into further development of the social evolution theory and the organic school. He proposed a structure of social interaction using the examples of production and distribution of collective ownership. The subject matter of sociology is spiritual interaction between humans assembled into social bodies (organisms). The main difference of human communities from an animal organism is the existence of collective consciousness. Social organisms struggle for survival and natural selection, as a result, only the fittest survive.

Rene Worms (1869—1926), comparing society with an organism, believed that they had a lot in common. He described society using the terms and notions of physiologists, anatomists and doctors. Anatomy of a society reveals its form and components — cells (individuals), organs (organizations) and tissues (social structures). Social physiology describes social processes, nourishment (when some organizations, communities, states and cultures are absorbed by others) and reproduction of individuals, social forms and structures.

His classification of societies reflects this vision of things social. He emphasizes that classification should be based on the anatomic structure of societies rather than on their physiological processes. Social anatomy indicates the current stage of society’s development. As for physiological descriptions, they can only apply to specific parts of society.

Considering social pathology, therapy and hygiene, he maintained that a society may be damaged by external influence or from within. The fabric of society may sustain a severe external damage penetrating through all the ways inside. And, vice versa, inner social diseases may leak outside. For example, bloodless parts of the fabric of society are rejected by means of mass migration. Another example would be a war, where contribution claimed by the winner can be compared with someone else’s blood transfused to the fabric of society and causing a disease. As a result, this brings suffering both to the winning and to the losing nations. The same would apply to industrial wars. Another phenomenon that is worth mentioning relates to parasitism when one society “piggy-backs” on another.

Public maladies can be treated by public medication, which, once used, may be called a public therapy. Using the healing forces of society’s nature is better than trying to heal the fabric of society. To prevent a disease, the rules of public hygiene should be complied with.

In the 1950—1970s, evolutionism developed into post-industrial theories, to be considered in more detail in the corresponding chapter. At the same time, evolutionism developed into neo-evolutionism (the socio-cultural evolution theory — an inter-disciplinary area across ethnology, anthropology, paleontology, archeology and historiography) and sociobiology (the sociobiological theory — an inter-disciplinary area across biology, sociology, zoology, archeology and genetics).

Post-industrial theories viewed social development as a single-line or universal evolution. Neo-evolutionists introduced an important aspect, viewing the development history of the global society as a multi-line evolution, with various communities and societies developing in different directions due to the need to adapt to different ecological environments (for example, climate zones or natural and cultural landscapes). The sociobiological theory of human behavior is based on the principle of genetic-cultural evolution, with natural selection going at the individual reproductive and group levels. Therefore, evolution applies both to the individual and to social forms.

Social Darwinism

Thomas Robert Malthus (1766—1834), the author of the book on human population, is considered the predecessor of social Darwinism. In the book, he made a futuristic prediction that uncontrolled growth of human population would lead to food shortages and hunger, saying that the poor would die out from hunger while the rich would survive.

Charles Robert Darwin (1809—1882) and his work about the origin of species made a great influence on the emergence of social Darwinism. However, Darwin emphasized that people were influenced not only by biological laws and conditions of life but by their skills to invent new tools and create new conditions of life. He also said that biological evolution of humans was incomparably slower than the development of technology and culture. In contrast with social Darwinists, Darwin never applied his concept of natural selection to humans, cultures and countries. As for social Darwinists, they use the ideas of Malthus and Darwin to propagate the ideas of militarism, eugenics and racism, which are now universally convicted.

Spenser also made a significant contribution to the development of social Darwinism. He is the author of phrase “survival of the fittest” and published the book titled “Progress: Its law and cause”, where he argues on progress of the universe as a universal law for the stars, human intelligence, and biological organisms, and introduces the notion of social progress.

Social Darwinism became internationally known in the late 19th — early 20th centuries. Its authors, while narrowing the patterns of social development down to objective laws of biological evolution, proclaimed the principles of natural selection, struggle for existence and survival of the fittest as the critical factor of social life. Social evolution justifies social inequality of individuals as well as of countries, cultures, peoples, races and so on.

Social Darwinism was further developed by authors who founded the geographical school in the 19th century. The geographic school ascribes the crucial role in the development of societies and peoples to their geographical location and natural conditions, including access to vital and strategically important natural resources.

For example, Henry Thomas Buckle (1821—1862), studying the history of England and its colonies, described the specifics of physical build, spiritual dimension and culture of various peoples and concluded that were interrelated with their geographical location, landscape, climate, soil and food.

Ecologism

Before moving on to ecologism as a socio-ecological concept and ideology, we need to describe the conditions that promoted its emergence. The context related to the circumstance that, by the mid-19th century, the stock of free land in the United States had been exhausted, setting the limits of economic growth. This became a constraint for the American democracy, which was viewing natural abundancy as a self-evident condition of social development.

The American society, having reached the limits of its expansion as the borders of its state had stabilized, and facing the aggravated social consequences of its external and internal policy, had to appreciate the close link between the social and environmental factors. This motivated its transition from an agrarian to industrial society (industrial growth and urbanization) and predetermined the understanding of the need to move from extensive to intensive use of natural resources. New socio-economic and environmental conditions gave rise to four main social reformist orientations, namely economism, conservationism, environmental movement and ecologism.

The strongest American orientation — economism, an optimistic orientation that implied a natural, spontaneous resolution of ecological problems, was characterized by an anti-reformist mood and a wait-and-see attitude. The supporters of this orientation believed that the existing social institutes were strong enough to cope with the crisis without any serious reforms. In this view, the natural environment was to serve private interest and individual initiative, and satisfaction of individual interests meant satisfaction of collective interest.

Their transcendental argument was the idea that Americans were a God chosen people endowed with inexhaustible natural wealth, both on the domestic and on the planetary-cosmic scale. Therefore, economists were opposed to the reformist projects proposed by environmentalists, who made very different forecasts. Economists pointed out that it was unclear who is interested in and who would carry out the reforms in a society which characterized by pluralistic democracy and liberal capitalism. At that time, environmentalists had no common understanding of barriers, immediate and final goals, the means for achieving them, possible deliverables and drivers for the reforms. However, they did have an understanding that social projects and reforms were needed to preserve the quality of social and natural environment.

The other three main directions represent environmentalism per se. In 1900, some conservationists were appointed to Government and received an opportunity to implement their projects as nationwide reforms. Their legislative and institutional reforms were aimed rational and efficient natural resource use, satisfying the needs of the American people for a long period.

Conservationists formulated the main principles as ensuring constant economic growth, prevention of unreasonable costs as related to natural resource use and an egalitarian distribution of natural resources. They adopted laws which helped to control the United States economy by the federal government to rule out non-productive and short-term use of natural and social resources by private business. According the opinion of conservationists, this was the possibility to move the American society away from the chaos of free market in a liberal capitalist environment and resolve a number of urgent socio-ecological issues.

A typical example of the new ecological legislation would be the adoption of the Lacy law, named after its author, senator from state of Iowa. The law, passed in 1900, regulated protection and legalized import to the United States of birds for hunting, singing and insect-eating birds, introduction and reintroduction of species “useful” for agriculture, preventing introduction of “undesirable” alien species that displace local “useful” ones. In particular, it prohibited the importation from the Old World some species of fruit-eating bats and mongooses, the ordinary sparrow and other species declared “undesirable” by the Ministry of Agriculture United States America.

This law was to strengthen the national legislation as related to fauna protection; in particular, it was aiming to prevent illegal hunting of birds to obtain their plumage used for decoration of women’s bonnets. The law ensured that poachers, as violators of the United States environmental legislation, could be prosecuted nationwide irrespectively of the United States state or foreign country law and from where the fauna items were illegally obtained. Another crucial achievement of the law was the requirement to obtain proper approvals for fauna items (for trade at the interstate level or trade with foreign countries) and proper markings of cargos. So, the law restricted the rights of individual states in these matters, regarding national priorities as being of paramount importance.

Reconciliation between the free entrepreneurship of private business and centralized government control became possible when an intermediate version of the law was passed. The idea was that businessmen were themselves to subsidize the legislative reform proposed by the government, however, the laws were, on the one hand, universal and, on the other hand, they allowed business to make its own decisions, in coordination with the local communities, locally, including in other countries. Generally, conservationism was oriented to perfecting methods for managing the natural resource use rather than to propagation of environmental values and nature protection.

Subsequently, conservationists were blamed for a number of antihuman and antisocial ideas, for example, the idea proclaiming the need to stabilize the planet’s population and even decrease it to one billion or less. In the second half of the 20th century, the corresponding conservationist solutions, ranging from economic stimulation of birth control in China to forced sterilization in India, were made at the national states level. In the beginning of the 21st century, conservationist “greens” push for a ban on industrialization and technical development of third countries (construction of power plants and manufacturing enterprises) and a radical shut-down of the already operating enterprises in the developed countries, paying no attention to the economic conditions and social consequences of their proposals.

The environmental movement, a trend within biocentrism, defended preservation of wild nature, which, in their opinion, has a value of its own irrespectively of its utilitarian use. For example, in 1872, the United States biocentrists established the public organization Sierra Club. Their views were based on a romantic understanding of nature. They introduce the social into Mother Nature, which is viewed as a perfect creation with spiritual qualities that encapsulates all things living and rational.

Biocentrists view the human life in nature as a certain mode of being and type of behavior, when protection of nature and rational use of natural resources may be just an external manifestation of in-depth motives and value-related orientations. Subsequently, the supporters of this ecological public movement have done a lot to preserve wilderness. Together with industry experts and the government, they developed a natural reserve concept, and such reserves were selected and formally established.

Today we can find a huge number of international, national, regional and local public organizations and civil initiatives for environment protection. Among themselves, they interact as networks or as partners in specific projects. Older large organizations retain a hierarchic structure. They are supported by local informers, who report violations of the environmental legislation or ecological emergencies. After that, the media and lawyers, responding to petitions filed by individuals or organizations. Where laws need to be amended, volunteers or social networks are used to gather a large number of signatures. At a “quiet” time, environment protection non-governmental organizations provide ecological trainings, raise public awareness, organize and conduct ecological holidays and festivals, various ecological events.

Worldwide and local activity of public environment protection organizations is quite significant and includes managing territories other than fit in administrative boundaries, for example, forests certification of the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC), wetlands and marshes of the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN), eco-regions of the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF), and virgin forests of Greenpeace.

Advocates of ecologism were typically represented by researchers who were building scientific models of interaction between society and the natural environment based on consistent patterns of natural sciences, i.e., on ecology. They were using an ecosystem approach implying that individuals, local communities and the humanity in general must be optimally fit into the ecosystem, look after its wealth, ensure an optimal functioning, and prevent crises and catastrophes, including those of a planetary scale.

In this view, the main role of the humanity on this planet is to preserve a dynamic balance of ecosystems and biological diversity. Ecologists combined features typical for the conservationism shown by the government bodies in charge of environment protection with the biocentrism of the environmental protection movement.

The purpose of the American Environmental Society, established in 1915, was studying ecosystems, including human communities. Another very important goal related to promotion of this knowledge and its inclusion in educational programs. The third goal was reforming the American society to turn it into a model of socio-ecological development.

Frederic Edward Clements (1874—1945) believed that the notion of culminating points was applicable not only to biological but also to social systems.

Aldo Leopold (1887—1948) proposed three main socio-ecological ideas that remain relevant until today. The first idea was the notion of an ecosystemic holism. Leopold believed that “…a thing is right when it tends to preserve the integrity, stability and beauty of the biotic community. It is wrong when it tends otherwise”.

An ecosystem, which incorporates a social system, becomes emergent, developing new qualities characteristic of a socio-ecological system in addition to the sum of its earlier qualities. Given the contextual and unpredictable nature of the ecosystem, its vitalism cannot be fully cognizable. The social, where it correctly interacts with abiotic and biotic items, structures and communities, leads to an optimal result of evolutionary development — the culminating point of dynamic equilibrium. Disruption of an ecosystemic equilibrium can only lead to degradation of such system.

Ecosystemic holism advocated by ecologists is useful in analyzing the kind of impact on given species and population, general development trends of the natural environment rather than a specific action and its consequences. It has the criterion of human rationality and, hence, is not synonymous with the transcendental nature of biocentrists. At the same time, ecologists are not trying to evade the question: How can one reconcile ecosystemic holism with liberalism — the discretion to choose one’s path of development?

This issue is resolved in the ideas of biotic functionalism and a biotic moral community proposed by Leopold. He maintained that a biotic moral community expands application of moral rules and, afterwards, other social institutes to non-human elements of the global ecosystem. The possibility of linking the human and non-human elements is made possible as ecologists assume that the notions of a “symbiosis” and “model of conduct” are functionally equivalent.

As a result, ethics becomes ecological and is presented as a conscious restriction of freedom of action for the sake of life on planet Earth. An ecologically responsible social behavior also implies establishing social institutes for restricting those people who are not oriented to this type of behavior. The human is perceived as the creator of qualitatively new types of environment and biotic communities, therefore, individuals are granted the right of individualism, which the non-human species may enjoy only at the specie population or the entire specie level. This right is based on the human ability to respond to changes in the natural and social environment in a reasonable manner.

The idea of biotic functionalism, enhanced by the idea of changing the man’s role in the biotic moral community, does not assume that an ecosystem as a superorganism (a supersystem) absorbs society (a subsystem). Ecosystemic holism rejects this idea, always preserving the integrity of the socio-ecological system and its emergent quality, when human moral rules allow retaining equilibrium, harmony and productivity of the ecosystem.

In fact, the modern-day socio-ecological concepts advocated by sociologists-ecologists emphasize and maintain that social interaction and development do not occur in emptiness and not in the social environment alone but also occur in the natural environment. And, in the context of a local ecological catastrophe of an anthropogenic nature or when the global ecological crisis is looming ahead, it becomes the main factor that determines interaction and development of society. Therefore, the nature-related character of social atomism, which theoretically could be combined with the evolutionary character of social change, was identified as early as a century ago.

Chicago school of sociology

The postulates of ecologism were appreciated and reproduced in the 1920s in the classical socio-ecological concept of the Chicago school of sociology. Below we will consider this in more detail. At this point, it should be emphasized that the methodological framework for socio-ecological research of the Chicago school of Sociology was provided, aside from the European schools of thought, by the ideas of the Chicago school of philosophy, formed earlier on. This concept is characterized by pragmatism and instrumentalism that combine philosophical humanism, sociological naturalism, social evolutionism and reformist ecological activism, including that of an individual.

The ideas proposed by the Chicago school sociologists were based on the evolution of the social, psychic and moral nature of the human, who emerged at a certain level of development of organic life and who remains dependent on the character and results of his interaction with the surrounding natural and social environment. Relationships between society and the environment change (and are changeable) by efforts of humans and the natural environment. Therefore, the task of a sociologist is not only theorizing, once the general patterns of such relationships and links are instrumentally identified, describing their structures and mechanisms, but also identifying best cases and practices that harmonize the life of humans in the environment. This can provide an example for everyone to follow, and a social reform to create conditions for its implementation, could be proposed to the government and business.

George Herbert Mead (1863—1931), together with other philosophers of the Chicago school, developed the idea of pragmatism, which maintains that truth and sense found in the cognitive process must have a hands-on value. This approach, motivated by the processes of urbanization and migration, brought new social issues and posed a problem requiring practical resolution by scientists.

He proposed the idea of symbolic interactionism: people differently respond to the same act by other people depending on the symbols apportioned to such other people. In the urban context of Chicago in the early 20th century, this translated into a situation when migration, uncontrolled by the city, led to the emergence of national ghettos and to other social problems. However, Mead was able to prove that these social problems were also caused by the way how a person perceives another person through symbols rather than via behavior.

This is a common mistake of cognition caused by the pragmatism of deceit and self-deceit. In the beginning, one generalizes the behavior of a social group, creating symbols, which are then apportioned to such group, whether males or females, peoples or countries, people of other faith or neighbors. After that, these symbols / assumptions are carried over to specific persons who have the identity or status of such group. The biggest problem is when spontaneous behavior of a specific person is not taken into account, when the desire to create social inequality, place oneself above this person and thus justify the suppression, violence or destruction being perpetrated, prevails. This situation was typical for uncivilized societies. In civilized societies, it is balanced by the legal system. While also being an instrument of violence that creates social inequality, court considers criminal acts of specific individuals.

If an ecosociologist, having summarized the results of a group research, the participants of which share the same identity or status, identifies a different behavior of a specific member of the group, he understands that this person realizes other identities and statuses that were unaccounted for by the sociologist, temporary situations, personal inclinations and so on.

John Dewey (1859—1952) made a significant influence on ecosociology as he developed the idea of instrumentalism within the framework of pragmatism. In his works, he maintained that the human nature combines biological and social components because they are functionally identical. This idea of biosocial parallelism implied that human instincts and social behavior are equivalent and need to be satisfied. After that, he only had to elaborate an instrumental base, i.e., methodologies of sociological research aimed at satisfaction of vitally important needs.

Where a need arises due to a disruption in the optimal functioning of the human organism in the ambient environment, its satisfaction is aimed at restoring equilibrium in interaction with the environment, and achieving the optimum. This implies a preliminary sociological study of a given situation, the interaction itself and its consequences for gathering of research materials. A sociologist may resort both to spontaneity and to experiment.

Individual experience is understood as integrity, interrelation, versatility, uniqueness and inseparability of things natural and social, organic and psychic, subjective and objective. This unity is a condition of freedom, expedience and responsibility, realization of all abilities inherent to human nature. This is the main task of a researcher — to develop empirical, including experimental techniques for distinguishing between moral and immoral behavior, help conduct political reforms aimed at transformation of qualities inherent to human nature.

Dewey regarded examples of interaction between individual actors (agents) in specific social formations (associations) as being the subject of empirical research. He viewed society as the process of association and communication when experiments, ideas, values become common for the participants. He was especially attracted to the ideal of creative democracy — a social organization with a minimized social control over individual manifestation of creative self-realization that rules out bureaucratic and hierarchical relationships.

At the same time, admitting that changing the human nature in order to achieve this ideal would be difficult, he was trying to address this issue as a pedagogue. Believing that only a useful knowledge is true and valuable, he developed school programs where, in the beginning, children were learning through play and afterwards — through teamwork and individual labor. For him, it was obvious that aside from biological restrictions, there exist social restrictions. Accordingly, another important aspect of education was to teach children the skills of adaptation to the ever-changing social and natural environment.

These ideas formed the philosophy of action, where a person actor (homo actor) performing the social role delegated to him, turns into an activist (homo active) characterized by natural morality and consciously choosing between his physical actions. This demonstrates realism and naturalism of the individual stream of experience, which is opposed to “bare” mentalism. However, this philosophy does not provide for nature’s development outside human actions and shows no interest for natural conditions, which may lead to extinction of the human race. Conditions resulting from the actions of humans and which could also lead to extinction of the human race were not studied either. Understanding of this and specific socio-ecological problems encouraged the elaboration by the Chicago school of sociology of the classic social concept of human ecology.

Environmental sociology, as an area of sociological research and theorizing, took its final shape in the 1920s — 1930s and is associated with such names as Robert Ezra Park (1864—1944), Ernest Watson Burgess (1886—1966) and Roderick Duncan McKenzie (1885—1940). They studied specific urban issues using quantitative sociological methods including systematizing and formalization of data gathered, territorial zoning and group segregation. This allowed studying the processes of deviant behavior, migration and adaptation.

At that time, Chicago as a social environment was a fascinating object of research. It demonstrated a complete set of situations and cases, which individually could be found in the other United States cities. Special attention was paid to labor strikes and demonstrations that often turned into mass civil unrest, migration processes and adaptation of ethnic communities, growth and organization of crime. As sociologists were eager to offer new ideas, they were expected to find ways for resolving these problems.

The socio-ecological concept proposed by the Chicago school of sociology was applied to a specific object / subject, relied upon an evolutionary approach to studying social change and the naturalistic approach to selecting methods of research. The Chicago school sociologists rejected Spencer’s theory of universal progress conceding to this notion only after generalization of specific research materials and admitting the possibility of progress in sociological cognition.

They emphasized a natural origin of conflict and the consistency of its transformation into an optimal state of consensus. This concept viewed conflict and consensus as interrelated and mutually complementary aspects of a single process of evolution. This description of the process of social change, the use for analysis of a tool for elaboration of dual, dichotomous and paired interrelated opposites determined the subsequent fate of the socio-ecological theory that combined a diversity of approaches.

The socio-ecological concept was based on the idea that society (urban community) is a complex system, organism and a biological phenomenon. Accordingly, in addition to the socio-cultural level, it has a biotic quality, which underpins all social development and determines social organization of the urban community. Therefore, in Park’s opinion, society forms at the biotic level while the cultural level emerges in the process of social evolution.

The starting point for analysis became the most developed social phenomena. Social evolution moves from the biotic to the cultural level and is driven by competition, which takes various forms in the course of evolution and achieves an optimum — competitive cooperation — at the cultural level. Competition forms the structure and regulates the sequence of change and restoration of equilibrium in the development of the social organism.

Social change per se looks as a process consisting of several consecutive phases, each of them being the result of the preceding forms of competition. After that, Park systematized and structured analytical conclusions. These methods allowed obtaining new knowledge and seeing phases of evolution and links between the biotic and cultural levels.

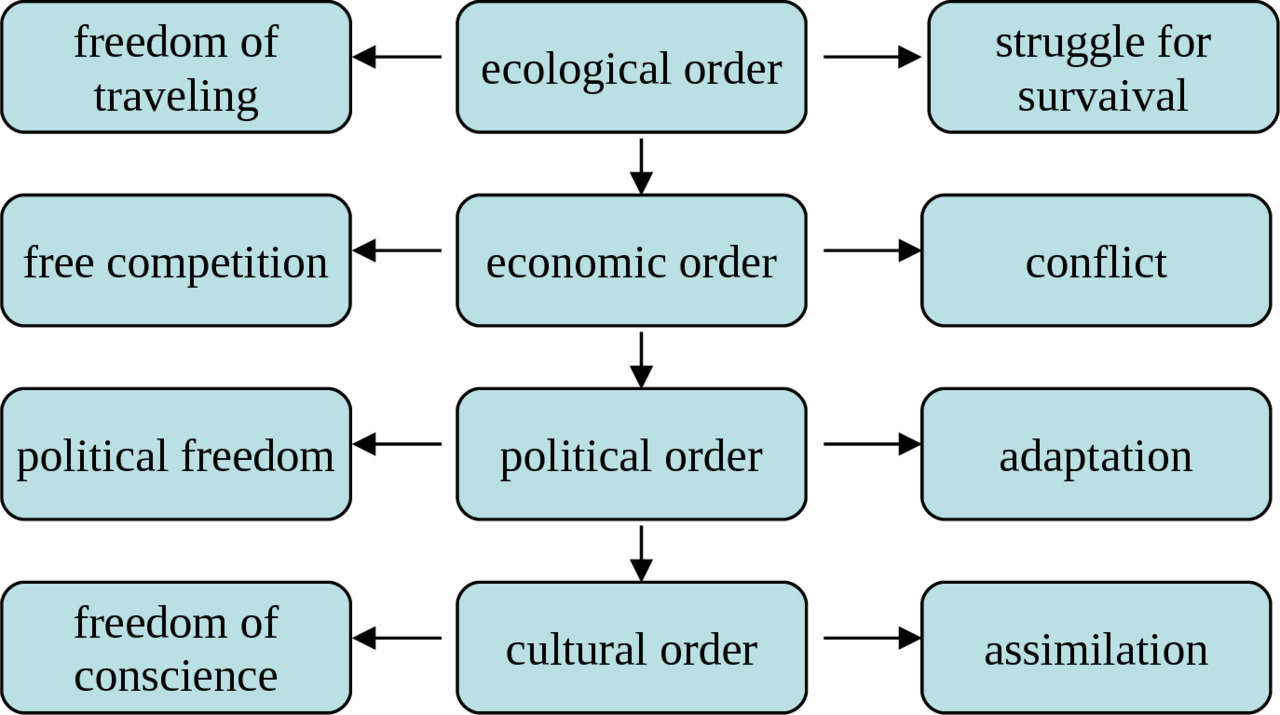

Park identified four phases of the evolution process from the biotic to social level: the ecological, economic, political and cultural orders. Accordingly, there exist four forms of socialization, namely, competition — struggle for survival on the biotic level, conflict on the economic level, adaptation on the political level and assimilation — on the cultural level.

All four are represented in the modern society in different situations (specific cases) to a varying extent (quantitative parameters) but with the same characteristic features:

— Ecological order is the result of physical (space-temporal) interaction of individuals. This order is characterized by freedom of traveling.

— Economic order exists where there is production, trade and exchange and is characterized by free competition.

— Political order prevails where there is control, management, regulation and enforcement. It is characterized by political freedoms.

— Cultural order is characterized by the dominance of morals, ethics, traditions, habits and customs, which form social institutes and structures, and which in turn, specify restrictions for individuals and society. However, this restriction is taken for granted as it is based on consensus.

Communication (interaction) capacity is inborn and makes a newly born baby a human. He is striving to communicate and this striving compels him to agree to curb his instincts, desires and aspirations. After that, social institutes and structures are reproduced as a result of collective action and consensus on a daily basis. Interactionism boils down to the postulate that individuals use communication to socialize and integrate. His process allows consecutive and coordinated action leading to a consensus-based or authoritative interaction, suppression of the minority by the majority, or majority of citizens by the elite representing a minority.

However, the anticipated interaction may not necessarily occur. Then interaction occurs in another situation in another form. This means that interaction is determined by the human nature. Interaction is based on movement, which characterizes the ecological level. This particular level is the subject examined by ecosociology, while the hierarchically structured superstructure — economic, political and cultural orders — are studied by economy, political science and anthropology.

Despite the attractiveness of studying the cultural level, the Chicago school ecosociologists, together with students, researched the urban environment fully using the structure suggested by Park. Naturally, they paid a lot of attention to the ecological level, which could be used for studying migration processes. Researchers acted on the assumption that a social organism consists of individuals capable of migration. Migration is a collective action and interaction typical specifically for the biotic (ecological) level. It is a basic freedom for all people irrespectively of the race and nationality.

Availability of higher-level freedoms (of conscience, political and economic freedom) is the subject matter of a new scientific discipline — cultural-anthropological ecology. The central concept of this science is “liberty” as a feature of modern society. The degree of freedom may increase or decrease on a case-by-case basis. For a human, the greatest external freedom is possible at the ecological level (in contrast with plants, humans have a freedom of movement), and inner freedom — at the cultural level (unlike animals, humans consciously choose their behavior).

On the one hand, all American reforms are supposed to be aimed at securing freedom for individuals and society and building a free American society. On the other hand, nobody ever plans or builds a free society; it emerges of its own accord where it does not oppress itself. And it emerges due to the biotic nature of humans — their ecological level. Therefore, the 19th-century wave of migration to the United States from China, Asia, India and Middle East indicates the switching of an in-depth mechanism that would change the existing institutes to build a qualitatively new society of free cooperation.

In the 1920s, the Chicago school ecosociologists received a few seats on the Committee for Local Community Studies. Participants of this inter-disciplinary research organization also included economists, philosophers, anthropologists, political experts and psychologists. They elaborated a common conceptual framework, conducted joint empirical research and theorized, developed recommendations for business and municipal authorities.

However, socio-economic crises and the subsequent Great American Depression of the 1930s formulated other national priorities. As a result, the socio-ecological concept of the Chicago school of sociology was used as a method without being developed into an independent discipline.

Attempts to rethink the socio-ecological theory made by Park’s followers were aiming to overcome the biosocial dualism of Park’s concept and make social-ecological theory more sociology sounding. Louis Wirth (1897—1952), having constructed a purely sociological theory of urban life, proposed to get rid of eclectics that allowed various interpretations of urban processes by scientists representing different disciplines. Interaction / communication continue to be the main characteristic of social processes and a driving force behind the development of local community.

To overcome the excessively broad theoretical orientation of the socio-ecological concept, he proposed a thesis that interaction becomes intensive with a large congestion of people on a constrained territory. He suggested a method for distinguishing between urban and rural communities:

— The first characteristic of urban population relates to its high density (the ratio of the territorial size to the number of residents).

— The second characteristic is the diversity of population (a large number of different social groups).

— The third is to prevailing social relationships (communal in a rural and social / mixed — in an urban community).

Therefore, the space-temporal aspect remained a characteristic of society, while ecosociology came to be perceived as a science that measures and describes the social environment.

To define the main ecosociological categories, McKenzie pointed out an ecological organization as a spatial body of the population in a local or the global community. He argued that ecological things dominate all other characteristics because they all are a result of space-temporal relationships. Accordingly, he gave priority to studying and theorizing on the phenomenon of the ecological community.

The followers of the socio-ecological concept maintained and continue to maintain that all social processes are in fact ecological. This understanding was to be the foundation for all social sciences, as the social institutes and structures are built on a space-temporal foundation, emerge and exist in accordance with the changing natural conditions, and nothing exists beyond these conditions.

This approach was enhanced by the fact that such socio-ecological methods as zoning and social mapping were successfully used for identifying and verifying the correlation between various social variables, which at first glance were not interrelated. Moreover, the use of these methods and conceptual approaches made possible generalized descriptions of various multi-variable cases, giving at least an understanding of functional, if not causal dependence.

An effective use of the socio-ecological method can be also explained by the level-based approach, which is similar to the principle used in system analysis when the phenomenon of a local community (social organism) being examined is analyzed in its interrelation with its higher (macro) and lower (micro) level. The lower level is the individual and the higher level is represented by social “compositions” consisting of various communities united into municipalities.

However, causal links of social organisms with their habitat and issues relating to optimal life support were not yet studied by ecosociology. Therefore, beginning with the mid-1930s, the abstract character of the ecosociology’s space-temporal functionalism came under criticism from representatives of the socio-cultural school, who emphasized the dependence of natural resource use on cultural traditions, values, symbols and norms.

Milla Aissa Alihan proposed a new vision of society and started working on a methodology for analyzing the social sphere within the framework of the already existing discipline — urban sociology. Three main variables — social standing (status), urbanization level (population density) and degree of segregation (multiplicity of social groups) — were identified. A city was described as a subsystem comprising greater territories and larger communities. In doing so, researchers were using data obtained from a census of urban population. On the one hand, this allowed analysis of cities rather than urban communities. On the other hand, this made possible, based on the statistical data received, a classification of subsystems (local communities). The result obtained could be rechecked some time later (sociological monitoring) to see social dynamics. This also enabled researchers to reasonably theorize on social organization as the main result of evolution.

Amos Henry Hawley (1910—2009), further developing the socio-ecological concept, was of the opinion that a community is an ecosystem (a territorial local system of interrelations between its functionally differentiated parts). Ecosociology may view a community as a population united by the similarity of its component organisms (commensalism). Human population is included into the ecosystem due to a mutually useful interaction with dissimilar organisms (symbiosis).

The focus of attention of the researcher-sociologist now turns to the functional socio-ecological system that develops in the process of interaction with an abiotic environment and other biotic communities. During such interaction, a specific social organization with specific characteristics is formed. Despite the fact that a civilized man prefers adapting nature to his needs rather than adapts to nature, and tries to irreversibly change nature’s characteristics and processes for his benefit, nature has resilience and is capable of influencing humans. It also can perform irreversible acts on humans.

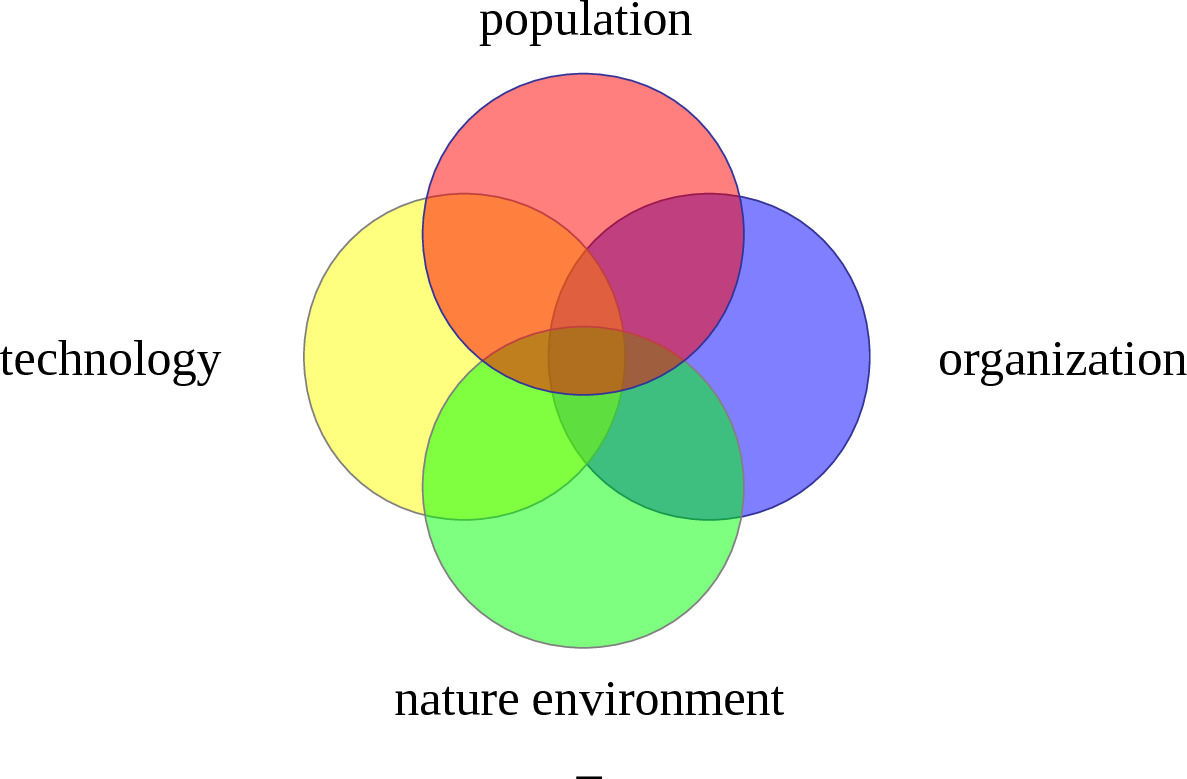

Finally, as the socio-ecological theories, approaches and methods are developed, social atomism is substituted with organizational functionalism; attention is focused more on the functioning of a social organization rather than on the driving forces and causes of this process or space-temporal forms of its manifestation. A description of this mechanism was made by Otis Dudley Duncan (1921—2004) and Leo Francis Schnore, who used the socio-ecological complex theory. The socio-ecological complex comprises four components:

1) Population (local human population);

2) Nature environment (abiota + biota + human populations);

3) Technology (things + means of production + culture of production);

4) Organization (social institutes and structures).

Park proposed an analogous structure of the socio-ecological process and studies of movement in time and space (communication and migration) as well as unique events (artefacts) determined by culture. Duncan and Schnore focused on the functioning of social organization, believing that this component was of most importance for their research. Making a social organization the subject of their analysis within the framework of ecosociology, they used quantitative methods and, based on the data obtained, proposed a thesis that it is a collective adaptation of the human population to the environment.

This approach was also different from that proposed by Park, where the population of a city, state, country and planet represented the macro level. A new understanding of the socio-ecological process as the functioning of a social organization allowed ecosociologists to conclude that samples of interactions that provide an ecological niche for the community, are the analytical unit. Therefore, society was viewed as a human population that was trying to use the environment’s resources to preserve itself (survive) through adaptation.

However, understanding the importance of the space-temporal linking of the social organization’s interactions being described and analyzed, ecosociologists were yet unwilling to use physical characteristics of the natural environment for their analysis. This was due to an observation that the physical environment in cities is much technologized and designed to suit the needs of humans rather than the biota.

Accordingly, in cities, the main impact on human population is made by the social environment, which replaces the natural environment. Ecosociologists then described and interpreted social phenomena using biological terms as “predatory”, “parasitic”, “dominating” and “symbiotic” relationships. This method was to socialize and defend the independence of their discipline.

The approach taken by Duncan and Schnore was perceived as oppositional to other approaches to studying the social organization, namely, the culturological and behaviorist approaches. However, this was an opposition to the constructivist approach that used new but already proven tools and methods of research that were getting closer to an explanation of social reality.

Sociologists-culturologists tended to make descriptions or analyses, starting and ending with social sphere, without any space-temporal linkage. Sometimes, they did use the word “nature”, not in the sense of nature proper but intending to emphasize an unconditional, inborn, natural quality of a social objects or subject.

For ecosociology, explanations offered by behaviorists were considered unacceptable at the macro level because no individual and collective human behavior existed at this level. At the macro level, interaction was limited to social institutes and structures (consisting of organizations) in the context of climatic zones, continents and other major space-temporal natural formations.

There was no way of determining social organization via neither existing cultural conditions nor social-psychological behavior-related affirmations. The new methodology proposed by ecosociologists enabled a breakthrough in studying the phenomena of human behavior and culture. The principle of functional interaction of the environment and social organization, as well as the well-developed conceptual framework of biology made ecosociology popular but could not be used for getting closer to explaining many causes of human interactions.

However, sociology and other humanitarian disciplines recognized that the physical environment can and does influence society and human behavior. Therefore, sociology branched out into the old “traditional” sociology, which maintained that social facts could be explained only with other social facts, and a new environmental (ecological) sociology.

Traditional sociology, using a sociologism-based approach, developed an attitude to inter-disciplinarity, which looked more as a ban on mentioning physical and biological environment. There also existed a disciplinary ban on status accounting for ecosystems and the consequences of their impact on humans and human communities. Violators, labeled as naturalists, were shunned by sociologists, who refused to quote or even notice them. Despite this, in the first half of the 20th century, several sociological works, linking human activity to the environment, were published.

Radha Kamal Mukherjee (1889—1968) was one of the first to conduct inter-disciplinary studies in the field of regional ecology within the framework of the sociology of labor. This research was done in India, a country different from the United States in many specific aspects.

Pitirim Aleksandrovich Sorokin (1889—1968) in his book “Man and society in calamity” summarizes almost 25 years of observations of social catastrophes, ranking epidemics and hunger together with revolutions and wars. He links social degradation and crises to natural calamities and catastrophes, which always go hand in hand.

Paul Henry Landis (1901—1985), within the framework of rural sociology studied miner’s communities and their social structure, linking cultural change in these communities to accessibility and richness of natural resources and other factors of the natural environment.

Fred Cottrell, in his studies of industrial sociology, analyzed interrelations between cultural forms of society and forms of energy. He concluded that the human civilization directly depends on technology and kinds of energy being used, showing the path of evolution from antiquity to the nuclear age, progress made by society and the resulting influence of economic, moral and social aspects. The issues relating to generation, transformation, distribution and consumption of energy remain one of the most serious issues over the entire history of civilization.

In the late 1960s — early 1970s, this gave rise to the following three organizational changes, which made possible further strengthening of ecosociology as a sub-discipline of sociology:

1) An informal group of sociologists, studying interactions as related to natural resources and natural resource use, splintered from the Society for Studies of Rural Problems;

2) The Society for Studies of Social Issues established a division for research of environmental issues;

3) The American Sociological Association established a committee for ecosociology. The main subjects of ecosociological research were natural resource management, recreation in wild nature, ecological movement and public opinion on ecological problems.

Ecosociology saw its practical tasks as being elaboration of models and programs for restoring the quality of the natural environment. This pragmatism ensured strong financial support for the research from interested business and the authorities. This allowed expanding the scope of socio-ecological approach, provided new explanations of causes behind typical interactions of society with the natural environment, including erroneous interactions fraught with adverse consequences for humanity and nature.

New environmental paradigm

Social situation changed in the early 1970s. Environmental awareness became the cause and source of more active ecological ideas not only in sociology but also in the international community. The discourse comprised with such notions as “environmental pollution”, “deficit of natural resources”, “overpopulation”, “negative consequences of urbanization”, “extinction of species”, “degradation of landscapes and desert advancing”, “dangerous climate changes leading to natural catastrophes” and so on. All these phenomena are now recognized as being socially significant due to their influence on the development of not only local communities but also the international community. As a result, they acquire a trans-local parameter.

Ecosociologists never missed the chance to highlight the existence of two main problems of the sociological disciplinary tradition, namely, the Durkheim sociologism and the Weber tradition of studying a single act and its significance for the individual. However, sociologists-traditionalists completely ignored the space-temporal, physiological, psychological and biological characteristics.

William Robert Catton (1926—2015) and Riley E. Dunlap proposed a “new environmenta0l paradigm”. It constituted a new stage of socio-ecological research and theorizing characterized by an interdisciplinary approach. The new environmental paradigm identifies two periods in the development of the sociological theory. The first one encompasses everything corresponding to the “paradigm of human exceptionalism”, which preceded the second period. The first one encompasses everything corresponding to the “human exceptionalism paradigm”, which preceded the second period. The second period relates to the emergence of the new environmental paradigm — the paradigm of human emancipation.

Referring to the preceding theories, environmentalists characterize them as anthropocentrism, social optimism and anti-ecologism. They emphasize that these are more than just theories but a way of thinking and a “modus vivendi”. Adverse socio-ecological consequences of the preceding period could be dealt with if the environmental (ecological) initiative becomes a mass movement and switches from anthropocentric consciousness to ecological one.

Older theories maintain that the socio-cultural factors are the main determinants of human activity, and culture makes the difference between a human and an animal. With the socio-cultural environment being the determinant context of interaction, the biophysical environment became somewhat alienated. Bearing in mind the cumulativeness of culture, social and technological progress may continue indefinitely. This is followed by an optimistic conclusion that all social problems can be resolved. The new environmental paradigm proclaims a new social reality:

— Humans are not the dominant species on the planet;

— Biologism of humans is no radically different from the other living creatures also being part of the global ecosystem;

— Humans are not free to choose their fate as they please, as it depends on many socio-natural variables;

— Human history is not a history of progress, which to a certain extent enhances adaptive capability, but a history of fatal errors, crises and catastrophes resulting from unknown causes and scarcity of natural resources.

The new environmental paradigm does show an understanding that humans are not exclusive specie but specie with exclusive qualities — culture, technology, language and social organization. In general, the new environmental paradigm is based on the postulate that, in addition to genetic inheritance, humans also have a cultural heritage and are hence different from the other animal species. In this, the new paradigm continues the tradition of the old paradigm of human exceptionalism.

Besides, even those sociologists, who did not subscribe to the new environmental paradigm, pointed out a traditional omission: society is not really exploiting ecosystems in order to survive but is rather trying to overexploit the natural resources for the sake of its prosperity, thus undermining the ecosystem’s stability, and may eventually destroy the natural base that makes human existence possible. This dilemma, initially posed within the framework of the new environmental paradigm, turned out to be so serious that representatives of other social sciences joined the debate.

Herman Edward Daly, within the framework of the economic sciences, presented the theory of a steady state economy, thus making a scientific contribution to the sustainable development concept, and participated in establishing the “International Society for Environmental Economics”.

William Ophuls, in his political studies, called for a new ecological policy while denying the very possibility of sustainable development. This assumption was based on forecasts of quick depletion of the planetary reserves of fossil fuel. In the end, under the laws of thermodynamics and due to inexorable biological and geological constraints, civilization is doomed. In his opinion, this was already obvious, given the rising tide of socio-ecological, cultural and political problems.

Donald L. Hardesty, who specialized in ecological anthropology, a subject area of the anthropological science, studied miner’s communities, the history of their cultural change, public living conditions, gender strategies and so on. He monitored how these communities were transforming the natural landscape into a cultural one, pointing out the accompanying process of toxic waste generation.

Allan Schnaiberg (1939—2009), within the framework of the sociology of labor, opined that social inequality and production race (“the treadmill of production” theory) were the main causes of anthropogenic environmental issues. From the Neo-Marxist positions, he criticized all “bourgeois” authors who were showing at least some optimism regarding the possibility of peaceful resolution of the socio-ecological problems (other than through class struggle and a change in the social relations of production).

John Zeisel, within the framework of the sociological theories of architecture, paid attention to important hands-on aspects relating to interaction of humans with the natural environment, believing that psychic, physical and psychosomatic peculiarities of people of different age require different architectural solutions.

Ecosociology now included the notions of an ecological complex and an ecosystem, considering the natural environment as a factor influencing the behavior of humans and society. One might say that ecosociology analyzes interaction between the physical (natural) environment and society. To perceive all forms of interaction between humans / society and the natural environment, it was proposed that organizational forms of human collectives, their cultural values and composition had to be taken into account.

Therefore, the natural environment influences all stages of Park’s social evolution and elements of the ecological complex proposed by Duncan and Schnore — population, technology, culture, social system, and the individual. In this context, the basic questions posed by ecosociology were: How can different combinations of all the above elements influence the natural environment? And how can one ensure effective change in the natural environment when these elements are modified?

Foreign authors of environmental theories

An important issue in ecosociology related to rethinking of the notion “environment”. By this, traditional sociology meant the social environment while ecosociology primarily meant the natural or biophysical environment. This division took some time to be accepted by all sociologists.

In addition, ecosociology made an attempt to go beyond the vision of a symbolic or cognitive interaction between the man and the environment. Ecosociologists were trying to prove that the surrounding natural conditions — such as air and water pollution, waste generation, erosion and depletion of soil, spillages of oil and so on — in addition to a symbolic effect, have a direct, non-symbolic impact on human life and social processes. This meant that, besides the impact made by polluted air and urbanized landscape on people’s perception of the same, one had to take into account the influence of this factor on physical human health when studying social mobility, and mental health — when studying deviant behavior.

In the 1970s, according Franklin D. Wilson, the focus of attention of social ecology and ecosociology shifted to the following issues: interaction of humans and the artificial (“built”) environment; organizational, industrial, state responsibility for environmental issues; natural perils and catastrophes; assessment of environmental impact; impact from scarcity of natural resources; issues relating to deployment of scarce natural resources and carrying capacity of natural environment.

Ecosociologists also noted the increasing influence of that part of public movement, which was showing concern over the state of natural environment and propagated such values as an environmentally friendly lifestyle and shaping a new ecological awareness, on social processes and institutes. These people were somewhat different from the environmental movement due to a greater emphasis on developing an ecological behavior and inner human potential (deep ecology). This difference is explained by the fact that these people were participants of other public movements and adherents of new religions rather than of the ecological movement per se.

Murray Bookchin (1921—2006), the main ideologist of ecoanarchism, studied social ecology-related issues, criticizing biocentric theories of deep ecologists and sociobiologists, as well as the followers of post-industrial ideas about the new epoch. He and other authors believed that a socio-ecological crisis was inevitable wherever state authority existed. All forms of governance are violence of man against man and nature.

In the opinion of ecoanarchists, a global ecological crisis could be prevented via decentralization of society and abandonment of large-scale industrial production. All people were to stop working for transnational corporations, move from metropolitan cities to small towns, rural municipalities, small communes and communities. Social relationships were to be regulated by methods of direct democracy and governed by direct right to life and natural resource use.

In the late 1990s, Bookchin refused to call himself an ecoanarchist, probably after seeing the implementation of his ideas in rural ecoanarchist communities and assuring himself that these ideas were inviable due to the impossibility of collective action and self-sufficiency, breakup and reverse migration to the cities caused by inequality and violence.

David Pepper, the ideologist of ecosocialism, and other authors were positive that the main causes of the socio-ecological crisis were the capitalist mode of production where society only exploited natural resources without producing them. In contrast with ecoanarchists, they suggested centralization of management (in the form of a state-controlled socialist economy), which was to help preserve nature as a universal human value.

In the 1980s, these ideas were still popular but radical socio-ecological reforms were no longer associated with major social change. Instead, they were associated with internal change in the individual and society, a change in the system of values and attitude to nature. They proposed to renounce anthropocentrism and replace it with biocentrism.

Arne Dekke Eide Naess (1912—2009) and other authors promoted the idea of deep ecology, suggested distinctions between social and natural, holism instead of dualism, i.e., the unity of man and nature, society and the environment. Homo economicus was to make way for homo ecologicus, a bearer of ecological consciousness, which, in the transitional era of ecological crises and catastrophes, was to be cultivated and developed. After that, all artificial boundaries (ideological, state, religious, race, cultural, gender, biological) were expected to collapse, and a New Age would begin.

As already mentioned above, ecosociologists also responded to the ongoing social change, proposing the new ecological paradigm, under which the paradigm of human exceptionalism would be replaced by that of human emancipation. These ideas were extremely popular among younger people and public movements addressing the issues relating to the quality of life. The power, industrial and financial elites could propose no viable alternative. Children saw no future in the activities of their parents. Society was afraid that it was edging towards a catastrophe and extinction. This situation could not last for a sufficiently long time and an intellectual breakthrough was needed.

The publication of expert’s works on limits of economic growth and the World Commission on Environment and Development report “Our common future” in the late 1980s gave rise to the popularity of the sustainable development theory, which will be considered in more detail in the chapter “Theories of sustainable development”.

Unlike ecoanarchists and ecosocialists, Albert Arnold Gore, one of ideologists of “green” capitalism, and other authors believed that industrial production, based on competition and profit generation, could be ecologized through state regulation and formation of new “green” markets. This did not make any changes in social relationships, but modernize them. This was to happen gradually and naturally as ecological challenges emerged, which were to be responded via new norms and rules for activities, behavior, morals and culture.

For example, demand for ecologically clean products has grown, causing structural and technological adjustments in industry, i.e., a modernization. An increase in the government annuity for natural resource use and penalties for pollution would also encourage modernization of industry (improvements in the technology used for extraction of natural resources), reduce generation of waste, save energy, and introduce recycling, closed and waste-free production cycles. This would also lead to changes in corporate culture — acceptance of the sustainable development concept, greater responsibility of business for socio-ecological consequences of its activities.

In addition to being a state, national strategy, ecopolicy is becoming a strategy pursued by international companies and corporations. They declare that, if used rationally, global natural resources are virtually inexhaustible and can satisfy the needs of the humanity indefinitely. Even if some resources are depleted, new technology would be able to provide new materials and products of a better, or, as a minimum, the same quality.

Problems of growth would remain in the form of demographic, informational and other “explosions”, which look catastrophically from the local management level, but can be dealt with via development and implementation of global programs. All interested organizations and individuals, who will form a new global design, could now be involved in a constructive dialog and decision-making process.

Therefore, those environmentalists, who had opposed industrialization, technocracy and bureaucracy in the 1970s, lost much of their popularity in the environmental movement by the 1990s. However, the first works published in the 1980s by authors who opined that management, industry and technology, which ensure the high standard of life of the modern society, were not ecologically dangerous per se and that they could be changed for the benefit of the environment, still were criticized.

In contrast with their European colleagues, the American environmentalists, who in the 1980s participated in numerous public organizations, state-run ecological councils and research expert groups, enjoyed the support from the population, government and business, were more optimistic. A considerable part of the United States environmentalists was hoping that ecological problems could be addressed via improvements in technology and management techniques, distribution of benefits, conservation and accumulation of the national natural wealth.

The intellectual breakthrough occurred in the 1980s when Josef Huber proposed his ecological modernization concept, which in the 1990s evolved into a scientific theory supported by business and the government. The theory of ecological modernization became quite popular among the European environmentalists, which allowed moving from confrontation to dialog and partnership with the state and business.

The ideas of ecological modernization are now largely accepted by the global environmentalist movement and implemented practically from the individual to state level. Because of scientific debate and hands-on experience, the theory of ecological modernization has gone through several stages of development and received both recognition and criticism. Several authors have proposed a number of development classifications. Historical and modern application examples have been studied, and a number of methodological approaches, allowing identification of independent lines of research, elaborated. This we will consider in more detail in the chapter “Modernist theories”.

Russian authors of environmental theories

In Russia, just like in the West, environmental theories were used by authors who included the natural context into their studies of social phenomena, who spoke of the mutual influence between humans and the natural environment and made interesting unusual conclusions. In doing so, they made a significant contribution in the development of sociology and the rise and development of ecosociology.

The specifics of Russian history make possible to split this scientific reflection into three periods — pre-Soviet, Soviet and post-Soviet. All Russian authors could be classified into those who represented the organic (sociological naturalism) and geographic school (social evolutionism), as it was done for non-Russian authors. However, for Russian authors, a division between these schools and principles would be quite notional.

Nikolay Dmitrievich Nozhin (1841—1866) had a considerable influence on his contemporaries, including sociologists. His views and publications are a good example showing the notional character of classification into scientific schools. As a biologist and a sociologist, he recognized Darwin’s biological evolution; however, he opposed Malthusianism and racism typical for some social-Darwinists. He was the first to propose an organic approach and formulated its main principles.

The main postulate goes that biological laws apply to human communities just as they do in animal species communities. Therefore, known biological laws could be used for explaining social phenomena and processes. A good example would be collective organizations — free associations of people based on the principles of solidarity and mutual assistance.