Бесплатный фрагмент - Zen Master Rilke: On Awakening to Beauty

and a Broken Nose

*

A Brief Appeal To the Reader

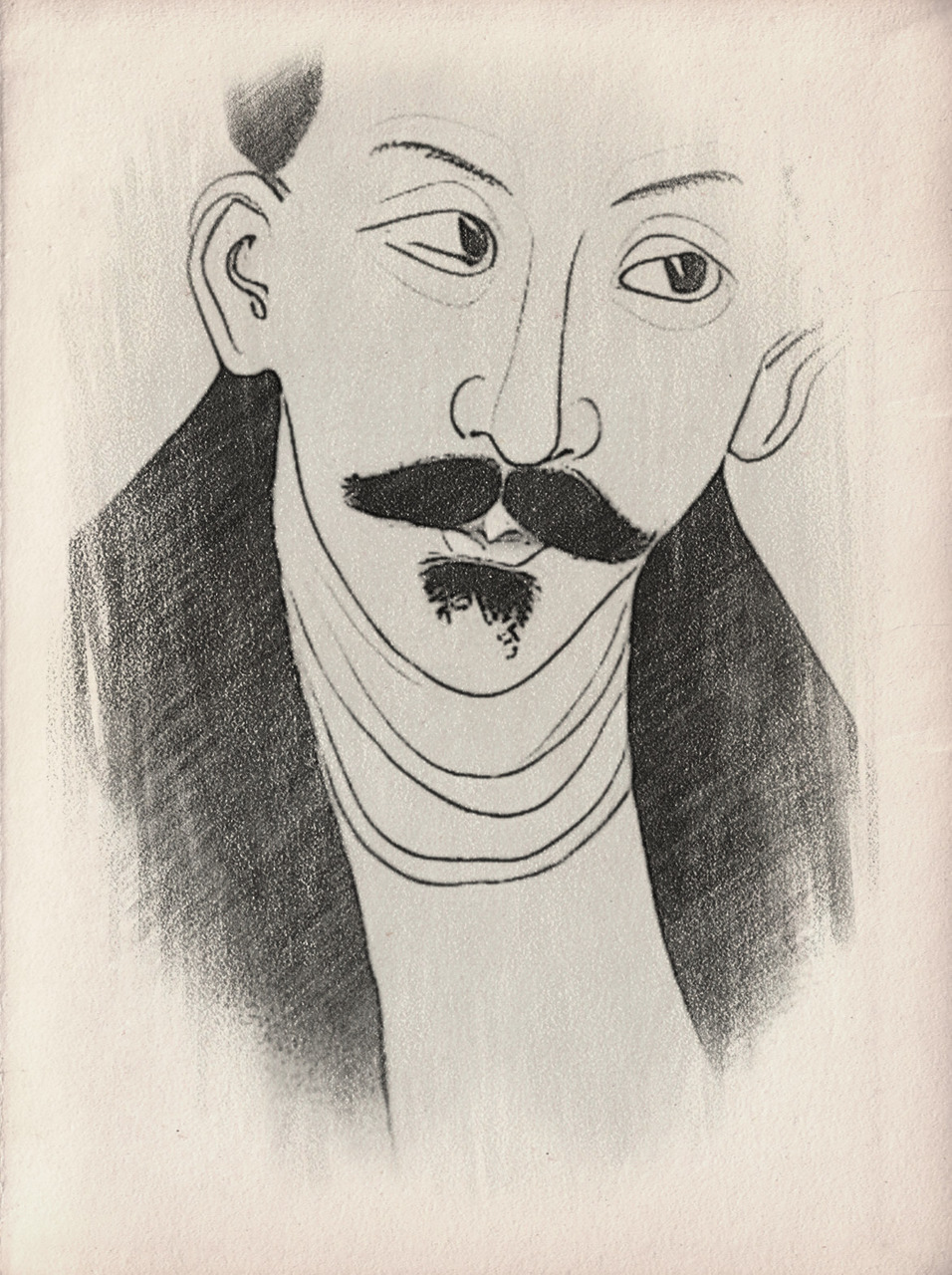

I must admit that I have tried very hard to organise and polish this book to an appropriate level of rigour, but it has still come out as quirky as a chaotic kaleidoscope. Nevertheless, I hope that even a cursory glance at the contents of the book will be enough to surprise the reader who is familiar with Rilke’s work, at least a little, and to raise natural questions: ´So what is the connection between Buddha and Rilke? And what can an early twentieth-century European modernist poet and an Eastern patriarch of non-action, who lived in the far seventh century, discuss for so long and so enthusiastically? And finally, what is the role of this strange head with the broken nose?´

As for myself, I still haven’t found an answer to any of these rather fair questions. Although, as the author of this book, I’m supposed to have found them. Otherwise, what would be the point of writing it? The only thing that excuses me is that I have tried to find the answers in the pages of this work, albeit with naive hope: first in the pathetic introduction on beauty, written, of course, on the basis of my own self-confident ideas. And then in the main text, in the dialogues which, although imaginary, involve historical characters with their authentic rather than fictional voices.

In order to finally arouse the reader’s interest in this book, I would like to assure him that it is not only the head of the old man with the broken nose that will be found in its pages. There is, of course, something more fascinating. A very rare and exotic butterfly, for example. A Chan butterfly of enlightenment. It is said that if it flutters even for a moment in front of the astonished reader, the primordial beauty will instantly reveal its true face to the viewer. And that will be the beauty that shines with its own light.

Gioconda with the smile of Nirvana.

*

...and Some Important Things To Know About the Book

First of all, I would like to emphasise that the title of my author’s Buddha-Rilke series in no way implies that Rilke was a follower of Gautama Buddha, or that his lyrical revelations should in the least be taken as such. It is well known that the poet categorically rejected all teachings. But his vision as a creator and artist was so multifaceted that it is not difficult to discern features of the most diverse philosophical conceptions in it.

Nor should the reader expect me to expound Buddhist doctrine: I have approached the philosophical literary sources of the Chan school primarily as artistic texts.

I would also like to draw the reader’s attention to the fact that, as he gets to know the book, he will find in it six remarkable poems by Rilke from his New Poems: ´The Swan´, ´St Sebastian´, ´Buddha´ in two versions, ´The Scarab´ and ´Buddha in Glory´; as well as the Ninth Sonnet from the Sonnets to Orpheus. All the poems above are given as my free prose translations, without regard to the rhyme and rhythm of the quoted original.

As for the dialogues presented in the book, they are all figments of my imagination, with a slight ´Buddhist´ tendency. It should also be said that all the characters’ speeches and all the phrases in the epigraphs represent a wide range of my own readings, from ´free flight´ to exact translation, except in the case of a few literal quotations, which are accompanied by obligatory references not only to the authors but also to the sources.

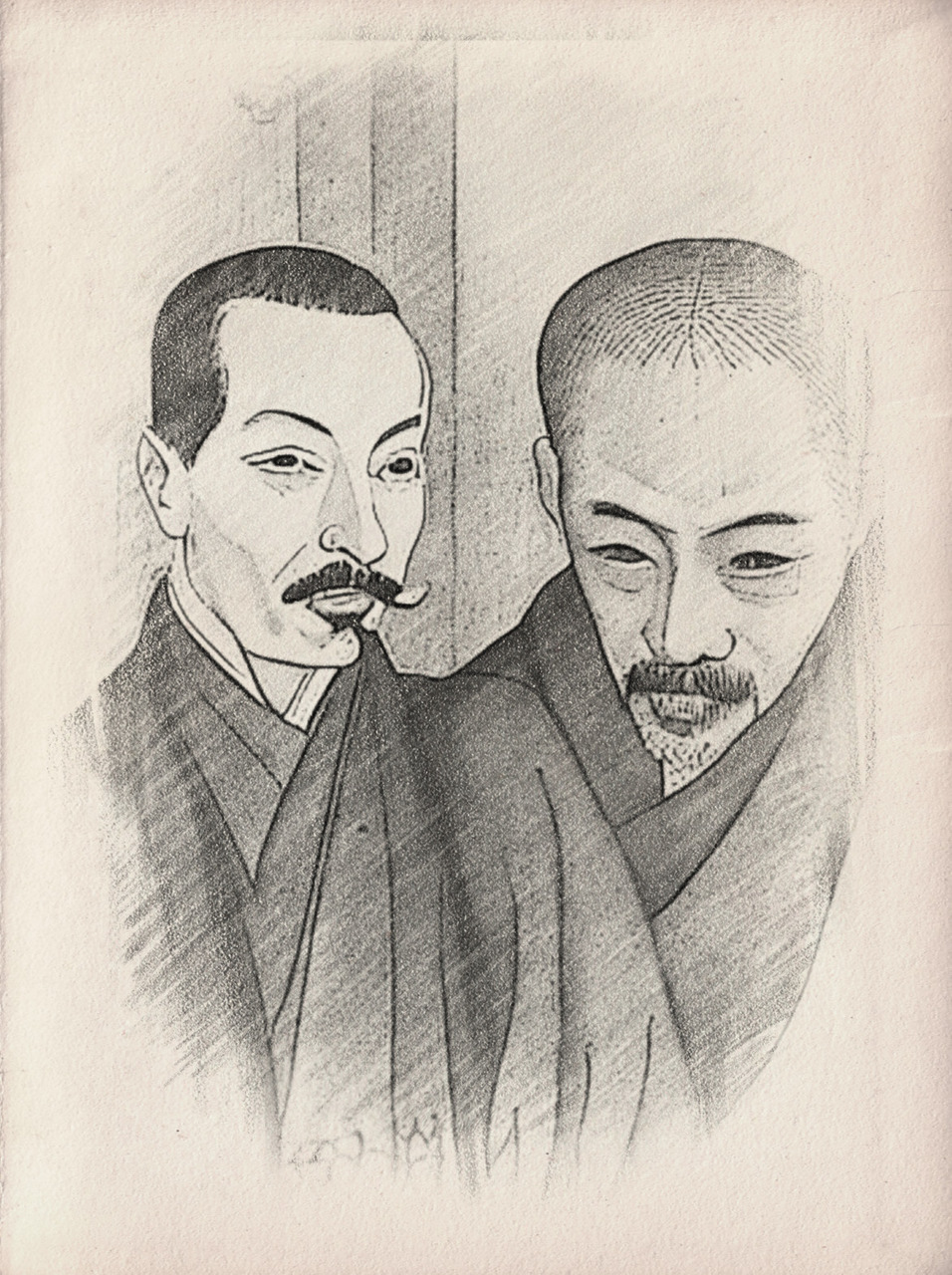

As soon as the reader begins to turn the pages of the Dialogues, he or she will immediately notice that R. M. Rilke himself is represented in the poet’s image. The textual material for the poet’s statements has been taken from Rilke’s famous essay Auguste Rodin, as well as from several of his letters, fragments of which I have attempted to translate accurately, while allowing for selective editing to ensure the semantic unity of the Dialogues. Such ´extraneous´insertions are indicated by square brackets.

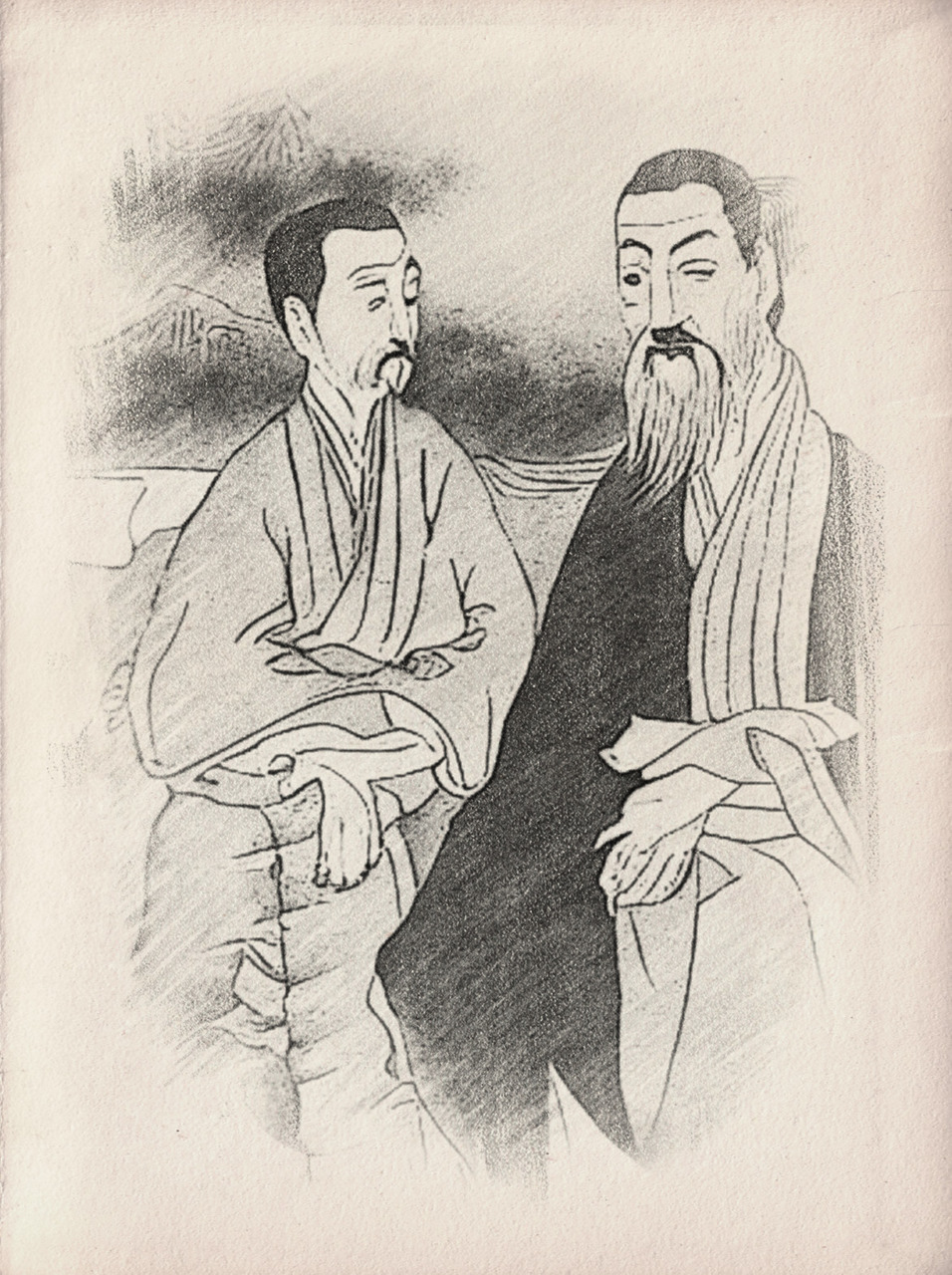

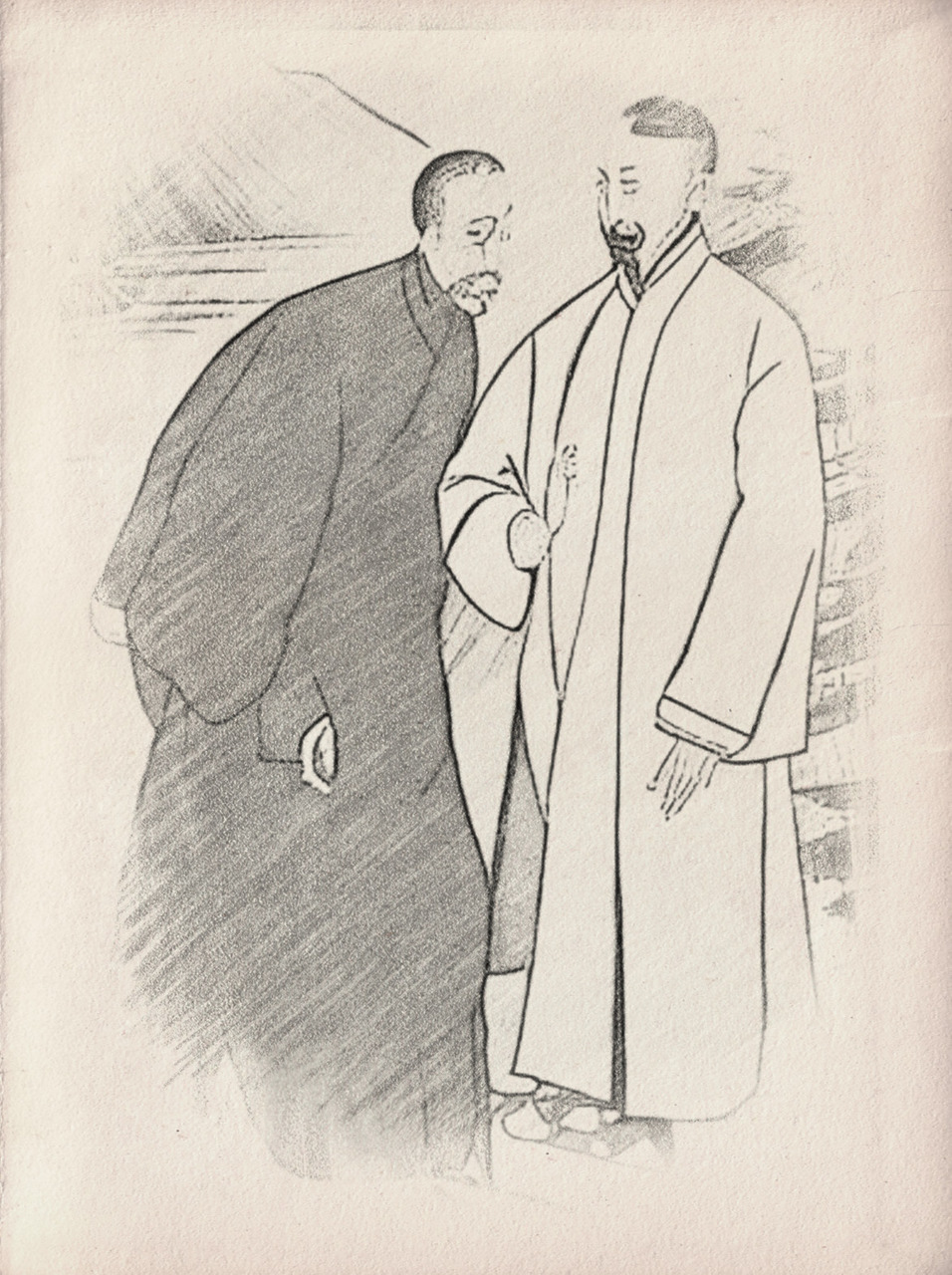

The image of the Patriarch is a collective one and mainly implies historical figures such as Hui Neng and Linji, the legendary masters of the Chan school. It should be noted that the Patriarch’s sayings are mostly my fantasies and arrangements, composed on motives of sermons and instructions not only of the mentioned great teachers, but also of such famous Chan (or Zen) masters as Sengcan (496? -606), Shih Wang Ming (6th century), Ummon (864 -949), and Hakuin (1686—1769).

The book contains a large number of illustrations, both my own and based on public domain images. The latter include works by such prominent Zen artists as Liang Kai (c. 1140—1220) and Hakuin Ekaku (1686—1769), as well as the lesser known but very ´expressive´ master Shi Ke (mid-tenth century).

*

Finally, I would like to express my deep gratitude to a very special mentor and person, Master Tho Idi, for his invaluable moral support, without which this literary experiment could hardly have taken place. And although Master Tho Idi seems to exist… only in my imagination, i.e. he is a fictional character in this book, I hope that this kind of gratitude on my part will not surprise the reader who is ready for ´surprises´.

After all, the reader is offered a strange book… with a touch of Chan.

A Few Words On Beauty

for which there is and can be no cause other than itself

Beauty precedes God.

— Master Tho Idi

*

A Paradoxical Meeting

And now it is time to return to our main characters, Gautama Buddha and Rilke, and ask ourselves again: ´Is there really anything that unites these two names? Isn’t such a ´rapprochement´ just a spectacular play on words, an extravagant fantasy of the author?´

Really, putting them together feels rather artificial at first, but then, as you delve into the ´theme´, something unexpected emerges between them that is worth thinking about, and eventually it becomes something exciting and grandiose that takes your breath away. For behind each of these names lies a universe of insight. All the more surprising when they

come together!

This book is an attempt to capture the vastness of that encounter. The author spent a long time working on the idea for this book, essentially asking himself a single question: ´What is the mysterious and omnipresent force that spiritualises these two such different names? What is the universal law that unites them?´ And at one point he even gave up the idea, realising his utter helplessness… Until one day ´enlightenment´ came upon him and he heard a single word, as simple and clear as God’s day:

Beauty!

An inviolable principle

Surely someone will find such a ´glimpse´ of thought deliberately far-fetched, or even trivial. For ´beauty´ is a lofty and all too tempting word. Especially as the sacramental immediately comes to mind:

Beauty will save the world.

It would seem that the great Russian novelist had already established beauty as an immutable moral principle. Is there really anything to add to these winged words? The author of this book is convinced that there is, and from an unexpected angle: it turns out that Fyodor Mikhailovich’s aphorism also has a hint of Buddhist meaning. It is hard to resist paraphrasing the Buddha:

Beauty is Truth! Beauty is the sacred Law! Beauty is the Teachings!

And it is hard to avoid giving Dostoyevsky’s visionary statement a new sound:

Beauty in itself brings us freedom from delusion, suffering and death!

If the reader is still in doubt, the words of the teacher Tho Idi will clarify the meaning of the above:

All things perish, but beauty endures! A mind established in beauty needs no more salvation!

Beauty Breathes Where It Wants To

We can recall another famous statement about beauty, although it sounds like an echo of Dostoyevsky’s aphorism. We are talking about the words of Nicholas Roerich, who said,

Awareness of beauty will save the world.

Disagreeing with the Russian classic, the author of the Living Ethics doctrine was convinced:

It is wrong to say: ´Beauty will save the world´.

As we can see, in Roerich’s understanding it is not beauty in itself, which is unchanging and eternal, that saves, but the awareness of it. In essence, the philosopher-theosophist subjected beauty to consciousnes. He also truly believed that it was possible to create beauty:

Man inexorably approaches the knowledge of truth and ascends to light through art, which creates beauty.

The patient reader who has read the dialogues carefully will easily come to the conclusion that Roerich’s ideas about the nature of beauty are profoundly… wrong! How can one be aware of, let alone create, beauty which, as Rilke succinctly and accurately put it, has

no image, no meaning, no trace of a name?

To be ´aware´ or to ´create´ beauty, doesn’t that simply mean to be bound by ´beauty´, by its form, its attributes, its visibility? And therefore,

the artist who is guided by this knowledge does not need to think about beauty; he knows as little as the others what it is made of,

the poet continues, formulating the fundamental aesthetic principle that the artist should follow:

No one has ever created beauty.

This paradoxical principle of the non-man-made essence of beauty is what the Master of Chan would have called ´non-thought´ about beauty. For true beauty rises to the impersonal, where there is no ego. On this point Master Tho Idi gave his explanation:

If you allow images, meanings, names for beauty there is a danger that you will begin to create an illusion. The causeless is not consciously graspable. It cannot be created. Beauty breathes where it wants to.

Is Beauty Not Prelest?

Beauty is often confused with prelest, which is ego-generated and a substitute for beauty. Therefore, spiritually immature minds are often ´enlightened´ by the idea that beauty is something man-made, and that it can be improved and even appropriated if one makes enough effort and learns its principles. Only the truly awakened know how irresistible and pernicious the spiritual prelest can be, and how skilled it is in the art of deception. In the soul-saving tradition of the Orthodox Church there are many examples of how even holy silent ascetics imbue beauty with false attributes peculiar to delirium (netvarnal ´radiance´, angelic ´illuminations´ and other high mountain ´lights´), which they regard as ´garments of their deification´. Alas, the souls of such ascetics revel in ´glory´ and clothe themselves in the ´splendour of the highest beauties´, often forgetting that

Beauty is chaste as long as its cover is nakedness.

It is not surprising that many theologians rely on the ´perfect illuminations of the ancients´, which turn out to be only a smokescreen, and give ´irresistible´ arguments to justify the ´beauties´ described above. Thus, some of these religious thinkers consider beauty to be nothing more than a metaphor for God, others consider it to be one of His attributes or holy names, and still others have given it an even more ´honourable´ place — to serve as an embellishment of the cosmos. For example, Gregory Palamas, one of the most authoritative Fathers of the Orthodox Church, an outstanding apologist for the practice of hesychasm, states that God, having created the world from non-existence, adorned it

…so that the universe could rightly be called ´cosmos´.

But there are also those who see in beauty… a charm that draws them to God. So writes St Maximus the Confessor, the author of the most learned scholia to the works of St Dionysius the Mystic:

God is called Beauty because He gives charm to everything and because He attracts everything to Himself.

And Dionysius the Mystic himself, the great theologian of beauty, when discussing the nature of beauty, clearly endows it with biblical attributes, calling it both the beginning and the creative cause, in the spirit of the Old Testament teaching. He thus replaces Beauty with God:

The beautiful is the beginning of all things, as the creative cause that moves and unites everything with the love of its own charm.

On this occasion it is important to emphasise that Beauty is beautiful in itself: Beauty has no beginning, no end, no purpose. The following wonderful words of Master Tho Idi should also be quoted:

The beauty of the flowering violet does not know that it is beautiful. It has no idea of God. And that it is the beginning of the whole universe and moves everything. Beauty is beautiful until it has no reason to be beautiful.

This is the opinion of the Mentor who really knows:

Only in the bud of non-knowledge, untouched by the burden of ego, is peace fragrant.

To what has been said we can add the following words of the Master:

Beauty does not belong in jewellery. Charms are the tricks of the ghostly prelest.

*

But perhaps beauty, which is neither born nor disappears, has been affirmed by philosophers who, we would like to believe, are so wise that they are free in their reasoning and far from the dogma of the Church? No, they have also defamed beauty, ´banishing´ it to the realm of aesthetics. They have robbed beauty of its self-existent ´soul´. For such thinkers, beauty has become an ornament of truth, its reflection, a secondary consequence; or a category of reason, an embodiment of the good, a function that elevates man to the divine realm; or it has been seen as the above-mentioned luminosity; or it has been thought to reside in its fullness in man’s nature only until his incarnation. There have also been minds that have assigned beauty the role of a silent concubine in order to ´purify´ themselves through the experience of ´harmless pleasures´: euphoria, catharsis, ecstasy and other spiritually exhilarating ´climaxe´.

Seek not euphoria, nor names, nor light, but Beauty. Happy is the one who abides in it.

— Master Tho Idi

´Doppelbereich´

If beauty is truth, if beauty is goodness, how can it coexist in man’s soul with his dark side and be for him only a prelude to horror (´schrecklichen Anfang´)? A reader familiar with Rilke’s work will certainly express such a perplexity, recalling his famous First Elegy from the cycle of Duino Elegies, in which the poet introduces us, from the very first lines, to the splendid and yet extremely dangerous world of angels. These admiring ´birds of the soul that almost kill us´ bring us not only their indescribable beauty on their wings, but also omens of horror:

If I were to cry out, who would hear me from the orders of

angels? and even if one of them were suddenly to take me

into his heart, I would immediately be crushed by his more

powerful existence. For beauty is nothing

but the beginning of the terrible, which we can hardly bear,

and we admire beauty because it is so imperturbably calm

and unwilling to destroy us. Every angel is terrible.

Is beauty, which spiritualises the whole world and determines all the laws of nature, only an appearance, only a prelude, only an occasion for horror? Isn’t Rilke contradicting his basic aesthetic convictions in this fragment? Not at all.

Terror will not seize him whose mind is established in beauty. Beauty reveals images of the eternal. It gives mortals the happiness of immortality.

— Master Tho Idi

Beauty threatens only the blinded self, the one who perceives the world as divided into ´this´ light and ´that´ light, the angelic sphere and the human sphere. Terror devours the confused heart that has forgotten its indivisible nature.

Here is Rilke’s succinct and profound answer to a similar question from one of his translators as to how his Elegies should be understood:

The affirmation of life and death in the Elegies becomes

a unity.

Бесплатный фрагмент закончился.

Купите книгу, чтобы продолжить чтение.