Бесплатный фрагмент - Novoslovnica

Guide for a Slavic constructed language

Acknowledgements

Starting this book I would like to appreciate some persons who had great influence on me writing this book. Such a work never can be done with efforts of a single man. I am grateful to those who believed in the project for the whole development period or just for a while.

First of all I want to thank Rafail Gasparyan. I suppose without his help and collaboration this book would have never been finished. And maybe so Novoslovnica would.

I would like to thank my Macedonian friend Kristijan Cvetanovski. His trust in Novoslovnica have been making me continue my work for all these five years. And with the help of him I discovered some important points that shook the grounds of the project a bit of times.

I want to thank my American friend Harris Mowbray and my Belarusian friend Sergey Yanchenko for editing English and Russian text of the work respectively.

Also I want to thank my Czech colleague Vojtěh Merunka for his critical view on this project. This made me rethink an amount of language details. Without that I don't believe Novoslovnica would have ever become a serious project.

I would like to thank my brother Ivan Carpow who spent his time and efforts on readting this book and making comments and corrections.

Moreover, I would like to appreciate persons that keep the inspiration inside me for these years: Manol Terziev (Bulgaria), Ivan Petrov (Bulgaria), Alexandra Getsich (Serbia), Ljiljana Bradich (Serbia), Igor Achkasov (Russia).

Foreword

Every language is alive - it is born, it grows up, it bares children and it dies.

The process of developing a language is unstoppable and it is cause by a lot of factors we cannot track.

What a beauty is a moment a new language appears. A lot of languages are old and appeared many years ago. However, there exist a very young ones were witnesses to be born i.e. Afrikaans (20 century), Yiddish (19 century) and extinct i.e. Prussian (18 century), Slovinian (20 century), Livonian (2013 year).

The language is naturally born doubly:

• by dialect divergence

• by two languages pidginating

The first way is much popular, though in pure form they both appear pretty rarely. This leads to differentiating of languages into a close language group.

Nevertheless, people sometime get into idea of reuniting these groups into a single language. This is not a natural way but we have examples of such a reunion. For example, modern German language was created from a group of different german languages and dialects to unite people into a single strong country. And they succeeded, so today we ahve a stable literary German language (though some region dialects still exist).

Moreover, people want to unite languages that have diverged much greater than German dialects did. It is rather enviable, though so many examples took place (Volapük, Novial). However, one of them, called Esperanto created by L.L. Zamenhof in 1887 year was very successful. Today more than 2 million people speak Esperanto and several thousand of them use it as a native language.

These examples show that the languages develop both ways - unification and divergence.

Novoslovnica as such a bridge for Slavic languages is working in direction of uniting the language. Collected expressiveness, beauty and purity of all Slavic languages, it tries to rework the idea of what a Slavic language should be.

It is not the only project in this sphere. Starting from Cyril and Methodius, Slavs continue to think about the idea of a common language when loosing the previous project in mind.

The need of a secular common language for Slavs is especially important since the twentieth century. The process of globalization is destroying weak languages and washing out a lot of root nests from others.

Novoslovnica in a row with other Slavic auxiliary language projects try to create something that Slavs could use to struggle the globalization process.

This book is for those who is interested in such an idea of a Slavic language reunion. Moreover, it reveals some historic features of our languages.

Hope you will enjoy reading this book and get something important for yourself when you finish it.

Novoslovnica is a standardized language project with strict rules in it that make the language able to be codified. Hope this will be useful for the interslavic community in developing the bridge between Slavic languages.

Whatever would be, anything you find useful in this book will make it worth writing, my dear reader.

You are welcome to write me all your wishes, comments and marks via email: support@novoslovnica.com

Best wishes,

George Carpow

Background

It would be right if we start the book with the article that was the first on the way to Novoslovnica construction.

The Slavic world has a deep and rich history. The Slavic tribes appeared on the vastness of Europe, and during their history of growth and development they have reached an extraordinary territorial vastness of settlement. We can say that the formed tribes of the Slavs lived on a huge territory according to Europe standards: from the Elbe in the West to the Volga in the East, from the Aegean sea in the South to the Neva river in the North. Further, due to the development of Kievan Rus and the Russian state, the Slavs settled throughout Eastern Europe and Siberia. Despite all the contradictions in politics and strife, the cultural and linguistic component of the Slavs continued to be preserved. Of course, the tribes bordering on other Nations have experienced enormous cultural and linguistic pressure, including Turkic, Roman, Finno-Ugric peoples.

Despite this, the Slavs retained their cultural identity and mentality. So, we can easily understand a person from the same group (Eastern, Western, Southern) and with little difficulty can establish communication with a person from another group of Slavs. This gives us the right to talk about the brotherhood of the Slavic peoples.

Many of the Slavic peoples have sunk into Oblivion, some in very recent times. For example, the Polabian culture left with the language by the middle of the 20th century. However, most of them remained alive, and from our common efforts depends on what will be the future of the Slavs.

From modern Slavic peoples only East Slavic group had relative stability and self-sufficiency. Russian experienced several waves of foreign language intervention — Mongolian, German, French and English, from which he, generally speaking, came out the winner, in many cases enriching and diversifying its vocabulary. At the moment, the English intervention, the strongest since the Tatar-Mongolian yoke, which has withdrawn many native Russian words from our everyday life, has not ended. But Slavs do it, assimilating came, and sometimes returning lost.

The situation is different in other Slavic groups. Not possessing constant sovereign statehood, Western and Eastern Slavs were subject to constant influence other peoples. Thus, the intervention of Turkish language in the South Slavic languages and culture can be correlated with the Tatar-Mongolian yoke for Russia. After liberation from Turks, southern Slavs have become to experience Western influence, and we can to see enough a large number of borrowing from English, French and camping on p. in Bulgarian and Serbian languages.

Throughout its history, Western Slavs were constantly terrorized by the influence of Romanesque languages. So, under the onslaught of the Germans, the Slavs lost their land along the Elbe and retreated to the Oder. Thus, the influence of the Romanesque tribes was also facilitated by the adoption of the Latin alphabet by the languages of the Western Slavs, instead of a possible Glagolitic or Cyrillic. Anyway, Slavs, though, and have undergone numerous impacts on their culture, managed to keep a common language to the present day.

The problem of re-consolidation of the Slavic peoples worried all many centuries ago and attempts were made to implement it. This can be considered the creation of Kievan Rus, the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, the expansion of the Russian Empire to the West, the creation of friendly relations with the Balkans, the creation of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, Yugoslavia, Czechoslovakia. However, the problem of the impossibility or short-lived nature of this Union arose not because of the establishment of friendly, fraternal relations, but the prevalence of the interests of one nation over all the other members of the Union, which inevitably led to the collapse and failure.

There is a fair idea that the inability to undertake such an Association is not only in the political interests of any country, Yes, undoubtedly, but also in the language of communication, state or Union language. It is impossible to make official all languages and adverbs existing in any district, and declaring one language more important than another we want this or not we turn ourselves to the further collapse of such relations.

The necessity and importance of the creation of the Slavic (pan-Slavic) language was realized in the 16th century, when the first attempts were made to create a common language for all Slavs. However, they did not bring the expected results and sank into oblivion.

Most recent developments of pan-Slavic languages are based on the principle of simplification, minimizing all vocabulary and grammar of languages. For example, these are Slovio and Medžuslovjansky. We believe this is fundamentally wrong, as the new language should not be aimed at the degradation of cultures, but rather to maintain the grandeur and beauty of Slavic culture and identity. Therefore, our principle is not to "Discard all that is foreign", but to "Unite all the best".

If we analyze why the Slavs need a new Slavic language, we can distinguish several positions:

• the need for an additional consolidating factor to unite the policy of the Slavic peoples.

• The need to strengthen mutual understanding and improve the Slavs ' perception of each other.

• Preserve the original richness and beauty of all Slavic languages.

• The impossibility of taking the role of the Slavic language of Russian (and Polish) due to historical reasons.

• Inability to accept the role of the Slavic language of the previous planned projects in full due to objective reasons.

Historical background

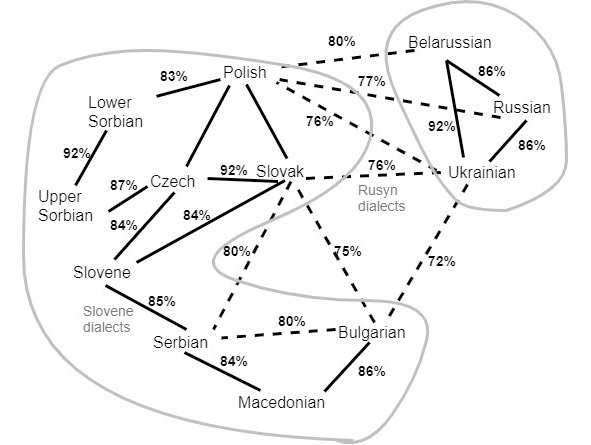

Baltic scientists in their research worked out a model of Slavic lexical identity. In the picture, you can see the percentage of common lexicon provided by connections between different Slavic languages.

There are three Slavic linguistic and ethnic branches - East Slavic (Russian, Belorussian, Ukrainian and Rusyn), West Slavic (Czech, Slovak, Polish, Kashubian, Silesian, Upper-Sorbian, Lower-Sorbian) and South Slavic (Slovenian, Serbian, Croatian, Macedonian and Bulgarian).

This division goes back into history. Different communication events with other nations, geographical position, territorial pecularity — everything affected Slavic people that became nations that now exist. It is supposed to have three initial tribes of Slavs: Venedes (the ancestors of West Slavs), Antes (the ancestors of East Slavs) and Sklavins (the ancestors of South Slavs). It is controversial, but a viable and a rather popular model within Slavic community.

Nevertheless, Slavs started to separate from each other in the seventh century. South Slavs came to Balkan peninsula and assimulated the Illyrian and Turkic peoples that lived there already. Thus, we see how Croatians and Bulgars appeared. The confrontation of Slavs and Germans lead to West Slavic peoples’ appearance. Spreading to the East and confrontation with Finno-Ugric and Turkic peoples poured out into the appearance of East Slavic nations.

Script background

One of the Central ideas of pan-Slavism is the creation of a common Slavic language. This problem was solved many times in one form or another and in different ways starting with the old Church Slavonic language created by St. brothers Constantine-Cyril and Methodius. The invention of the first common Slavic language is associated with the appearance of the first writing, which was to become common Slavic — Glagolitic.

However, over time, the part of the Slavs adopted the Cyrillic alphabet, the part took Latin, and some for a while had the Glagolitic alphabet, the Latin alphabet and a modified Cyrillic alphabet, known as bosancica or horvatica (there are other names). Glagolitic also changed, becoming from rounded "Bulgarian" an angular "Croatian". But the main thing was — the language itself changed. Once a common old Church Slavonic began to divide into version that started to converge with the live Slavic languages. We can name some versions of Church Slavonic: Russian Slavonic, Bulgarian Slavonic, Serbian Slavonic, Croatian Slavonic etc.

Attempts to solve the problem of separation of Slavic languages and scripts gave several options:

• To revive the Church Slavonic language anyhow with adding elements of live languages to it or without adding.

• Take one of the live languages, but with certain modifications — adding new letters or words from other Slavic languages, new grammatical structures and so on.

• As in the previous item, but do not change anything and try to spread the live language through educational courses and other forms of education.

• As in the previous point, but forcibly.

• Create a new artificial / semi-artificial language based on those elements of the Slavic languages that remain common or can be relatively easily reduced to common + a number of different elements, to facilitate the «entry» into the language of the Slavs who speak different Slavic languages, or on the basis of only common elements.

The second part of the problem is writing. Due to the fact that the Glagolitic alphabet and bosancica virtually disappeared and remained only in limited use (bosancica disappeared almost completely, and the Glagolitic alphabet is supported in Croatia), the remaining candidates for the Slavic alphabet stays Cyrillic and Latin.

Generally, it can be said that new interslavic projects often use the Latin alphabet that cuts obsessiveness of these projects, because Cyrillic and Latin alphabets still are native to Slavic writing systems:

• in one case, a literature began almost immediately with the Latin alphabet

• in the other a literature started with the Cyrillic alphabet

• somewhere both Latin and Cyrillic scripts are used

• somewhere the transition from Cyrillic to Latin script took place

In Yugoslavia, Cyrillic and Latin tried to lead to a common denominator through the creation of the so-called Slavica. The essence of Slavica was to leave the backbone of the Latin alphabet (all the basic letters + letters, the same for the Latin and Cyrillic), replace all the digraphs, letters with diacritics and digraphs with diacritics corresponding Cyrillic letters. In Yugoslavia, this was all the easier to do because the Yugoslav Cyrillic and Latin alphabet are completely identical in composition having a mutual transliteration of each other. However, this project failed because of the resistance of nationalists in Croatia.

Interslavic background

We all know that the idea of a common language for the Slavs hovers among the Slavic peoples for more than a Millennium. The first and only successful project to date was the Church Slavonic language of Cyril and Methodius. This language has successfully found its niche in religious use and is used with some changes to the present day. However, such attempts for the secular language were resumed only in the 17th century in the works. Moreover, the working project was neither created nor introduced into society, while some similar projects of planned languages for romance languages have successfully taken root and found a wide response in society (Esperanto, Interlingua).

The revival of the idea of the inter-Slavic language in our days occurred in 1999, when mark Gucco from Slovakia created the language of Slovio. This language has a huge number of shortcomings and is currently not recognized as capable by any of the developers of the inter-Slavic project, but it served as a catalyst for the emergence of a large number of such projects and the development of the idea of creating a planned inter-Slavic language that could meet the needs of modern society.

After that, more than 20 similar projects, more or less developed, appeared in 10 years. In 2006 there was a project slavianski, created (Ondrej Rečnik and Gabriel Svoboda). This language was developed in parallel in different degrees of detail, he put his ideas Jan van Steenbergen and Igor Polyakov. In 2009, the project broke away from the project Slovioski (Steeven Radzikowski, Andrej Moraczewski and Michal Borovička), which tried to unite the ideas of Slovio and Slovyanski. However, in 2010, all these projects were merged into one under the name Interslavic (see below - Interslavic-2).

At the same time, the Czech programmer Vojtěch Merunka published under the name of Neoslavonic. This project suggested the idea of how the Church Slavonic language could develop in free development. In 2011, these two projects began cooperative work on a common case. (see figure 1) then, this project has taken a leadership position on the issue of building medullablastoma language. Only in 2012 there was one project of “Northern Slavic language” (Venedčyna), presented by Nikolai Kuznetsov, who then joined Interslavic, and in 2014 there was a project of Novoslovnitsa, presented by George Carpow and the development team mainly from the countries of Eastern and southern Slavs, which at the moment remains the only living independent project outside the project Interslavic.

Interslavic introduced the idea of flavorisation, which resulted in a valid language differentiation of dialects and spellings and the lack of codification. In 2017, the project Neoslavonic and Interslavic merged into a new project called interslavic-2, which was a compromise between the ideas of Vojtěch Merunka and Jan van Steenbergen (who headed the project interslavic-1). They presented their new ideas in the article, which was published in July 2017.

Comparison with other projects

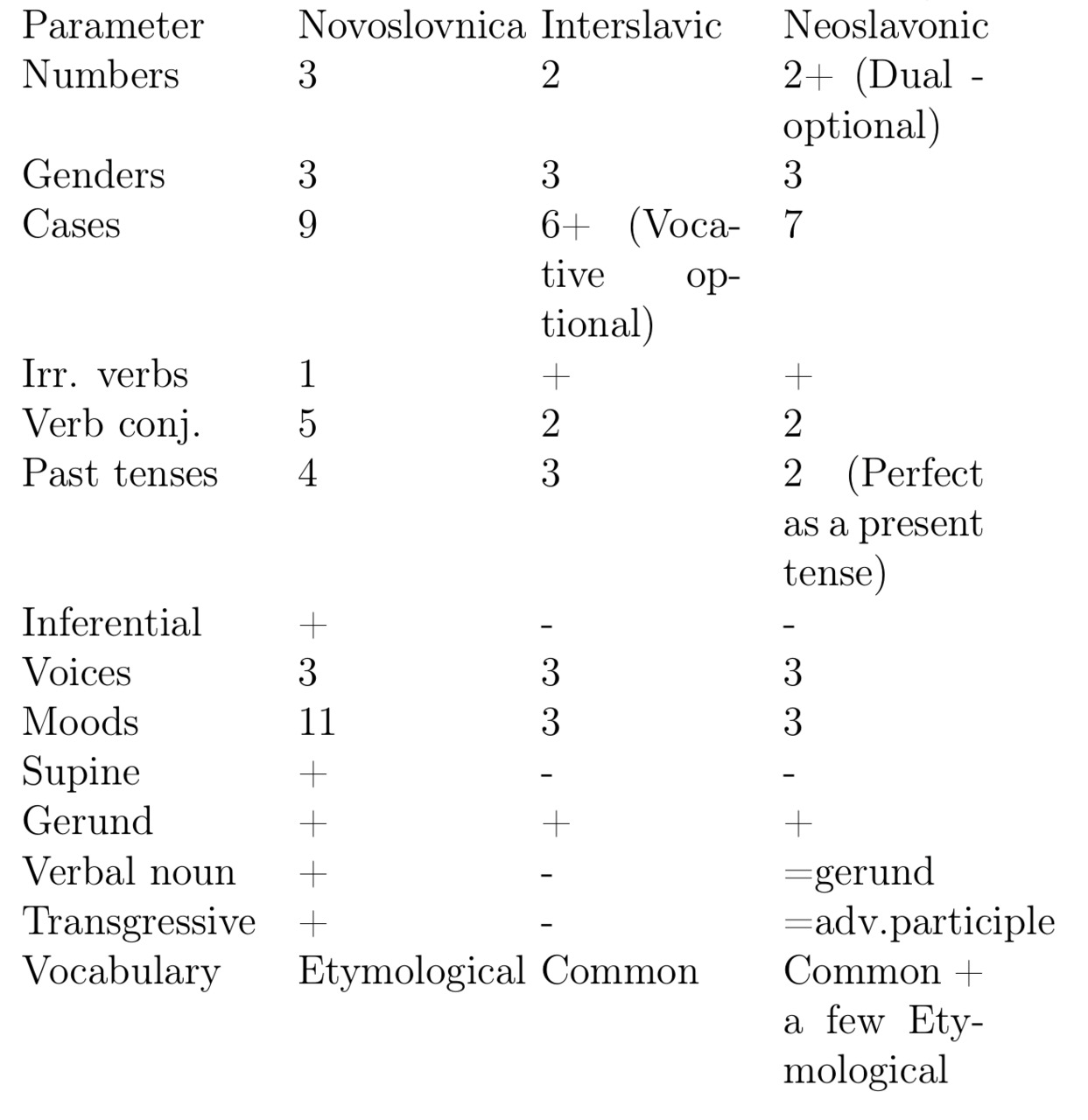

We can provide a little concept comparison of other interslavic projects: Neoslavonic and Interslavic.

These projects had been developed before Novoslovnica appeared. Each of the projects has its own flavor or aim:

• Neoslavonic represents the idea of the possible development of Old Church Slavonic up to nowadays.

• Interslavic-1 develops the idea of finding a common core of modern Slavic languages and take features and lexicon that is common to all modern Slavic languages

• Novoslovnica from this point of view develops the idea of creating the language that unites most grammar features assimilated by different Slavic languages along with etymologically developed lexicon with regard to modern days.

Phonology

Phonology — a branch of linguistics concerned with the systematic organization of sounds in the language. Phonology describes all the sounds that the language possesses.

Sounds can be divided into different classes. One of the characteristics for separating different sounds is the ability to pronounce them with an open vocal tract. You can notice that vowels (such as a, o, u in English) are able to be pronounced with open vocal tract, whereas consonants are pronounced with partly or completely closed vocal tract.

Moreover the term of allophone should be concerned before going further.

Allophone — one of a set of multiple possible spoken sounds or signs used to pronounce a single phoneme in a particular language.

This leads to the definition of a phoneme:

A phoneme is one of the units of sound that distinguish one word from another in a particular language.

Therefore, an allophone is such a sound (or a set of sounds) that does not influence the meaning of the word.

Vowels

In the beginning of this paragraph the description of a vowel should be given.

A vowel (V) — a sound produced with no constriction in the vocal tract.

With this information we can distinguish different types of vowels. The classification of vowels is based on two main factors:

• What is the row of the sound

• What is the height of the sound

• Whether the vowel is rounded or not

The row is the position of the tongue when you pronounce a vowel. There are three main rows: front, central and back. When you pronounce a vowel at the front row, you move your tongue toward the teeth. The descriptions of central and back rows are similar — you move your tongue to the center or toward the larynx to pronounce them.

The height of the sound is a characteristic of tongue convexity and tension in your mouth. If it is positive, it means your tongue does not touches the palate nor bottom of the mouth, and the tip of your tongue is tense- or closed. If your tongue is flat and parallel to the bottom of your oral cavity, moreover, it lies on it — it is an open one. Between these two positions a middle position can be found.

The roundedness of the vowel is the amount of rounding in the lips during the articulation of a vowel. Vowels can be categorized as rounded and unrounded. Thus, to pronounce a rounded vowel you should round your lips. To pronounce an unrounded vowel, you should relax your lips during the articulation of a vowel.

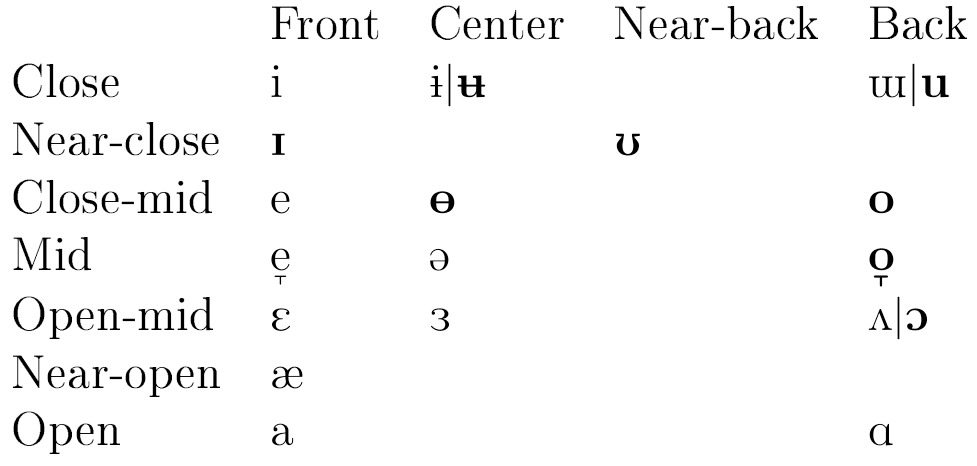

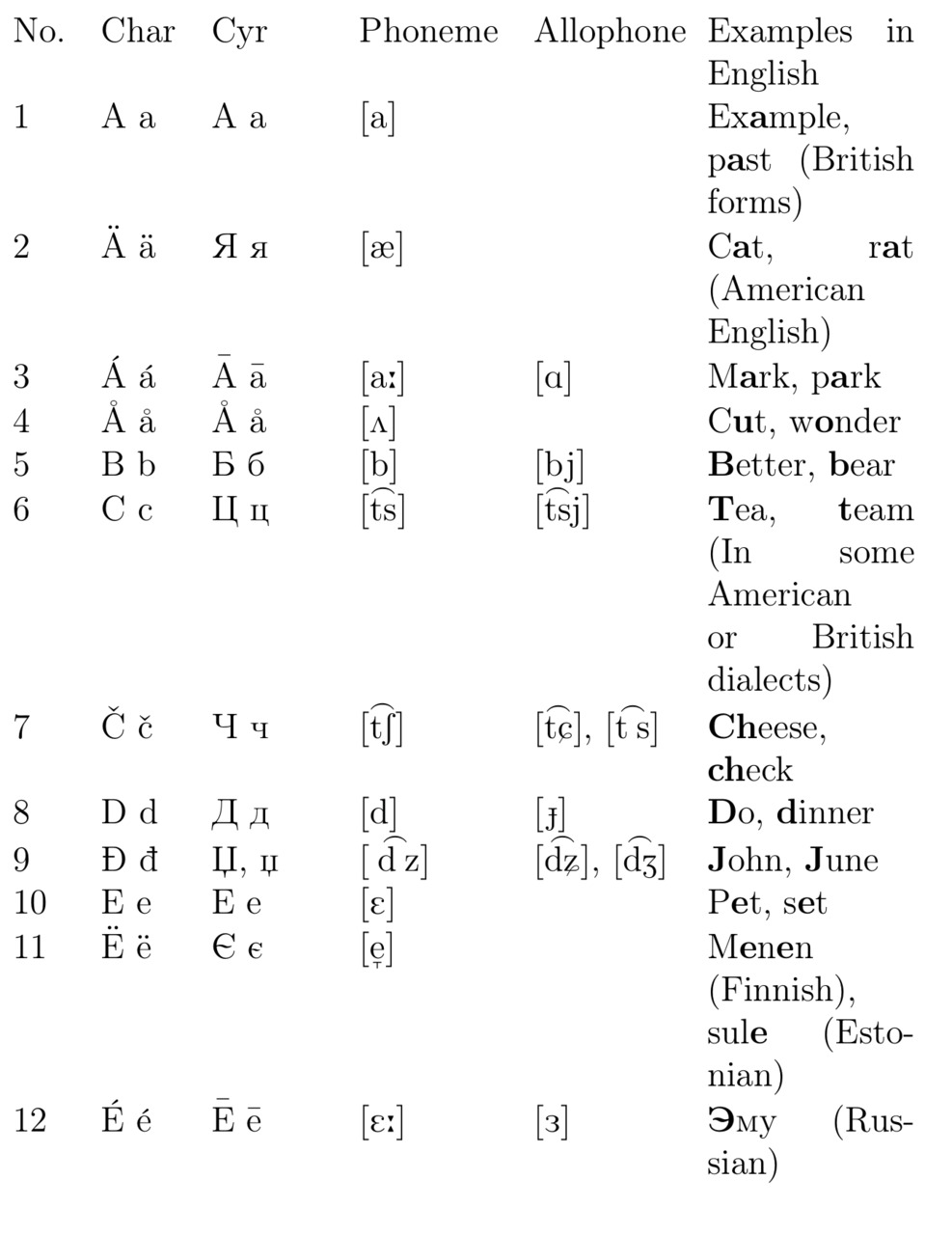

Finally, we can talk about Novoslovnica phonology. Novo-slovnica consists of 20 ordinary vowel phonemes. Among them there are seven closed vowels, three open vowels, ten middle vowels as well as seven front vowels, five center vowels and eight back vowels. On the table 1.1 you can see a chart position of the vowels in Novoslovnica.

In this table you can also see different vowels are font-styled differently. The bold ones are for rounded vowels. The normal ones are for unrounded vowels.

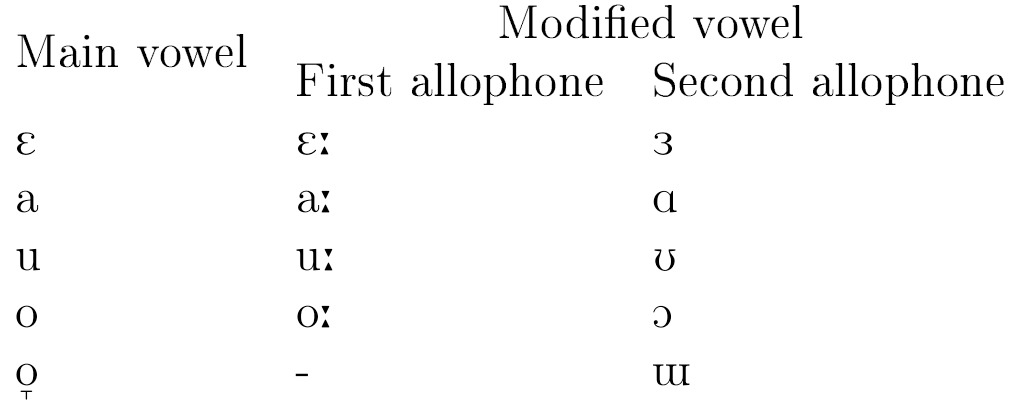

If you know Czech or Finnish, you might be concerned by the absence long vowels in this chart. It’s time to speak about allophones in Novoslovnica.

Novoslovnica has allophones of open and long vowels. This means that it does not matter how you pronounce a “modified” vowel — as a long one or as an open one — the meaning of the word will not change. To make this more clear, look at table 1.2.

Exception:

o̞ (only one modified vowel — ɯ)

Examples:

Buda [`buda] (Buddha)

búda [`bu: da] (building) — [`bʊda]

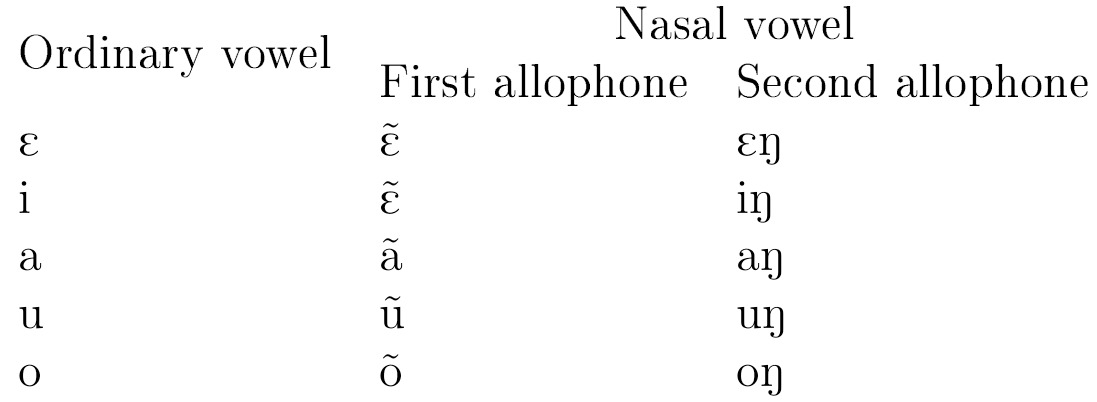

If you have some knowledge about Slavic languages and their origins, you should know that the Proto-Slavic language had nasal vowels, which we can nowadays be found in Polish and Lithuanian. Do they exist in Novoslovnica? Of course they do! There are two allophones for pronouncing nasal vowels. The first one is actually a nasal vowel, when you pronounce an ordinary vowel through your nose. The second is more common, such as in French, when you add a nasal consonant [ŋ] to an ordinary vowel. Look at the sounds on the next table.

Examples:

Dųb (oak) [dõb] — [duŋb]

Męso (meet) [`mɛ̃so] — [`meŋso]

As you can see, Novoslovnica distinguishes between nasal vowels in two categories — O-nasality (hard) and E-nasality (soft).

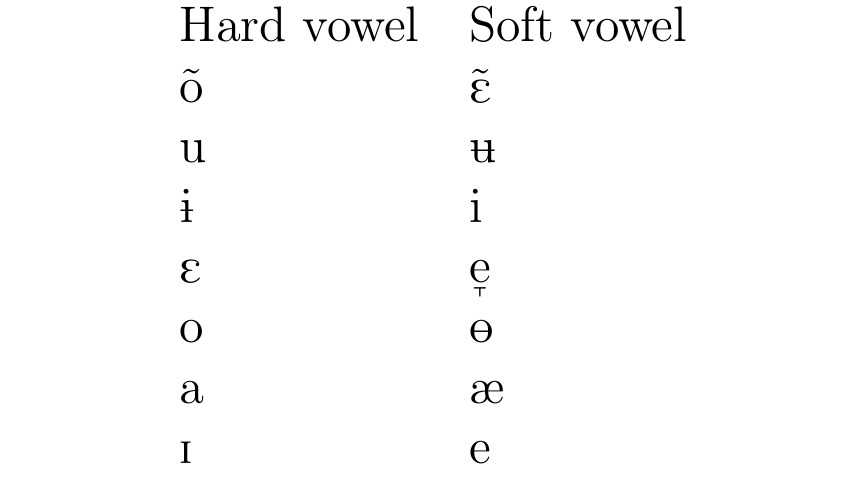

The last topic that we will speak of pertaining to vowels, is the firmness and the softness of the vowels. Scientists argue about what is primary in making sound soft or hard — consonants or vowels. Novoslovnica claim vowels are softer or hard primarily, although consonants itself also can be either soft or hard.

There are vowels that tend to make their surrounding soft and there are vowels that tend to make their surrounding hard. As you already know, there are two nasal vowels — one hard (O-nasality) and one soft (E-nasality). However, there are other pairs of hard / soft vowels among ordinary ones. Look at table 1.4 for more information.

Examples:

Dodatek (addition) [do`datek]

Smërtj (death) [sme̞rc]

There is only one vowel that has no pair in softness / hardness. It is ə. This vowel is named the «schwa» sound and it can be described as the most «middle» sound among vowels. To pronounce it you should relax your oral cavity and pronounce a sound with weakened muscles. This is the «schwa» sound.

Consonants

In this paragraph about consonants, I would like to begin with the definition of a consonant.

Consonant (C) — a sound that is articulated with complete or particular closure of the vocal tract.

Likewise vowels, consonants have three characteristics that determine their position in your articulation. These three parameters are:

• Place, where the consonant is pronounced in the mouth

• Manner, how the consonant is pronounced

• Sonority, whether you use your vocal cords or not

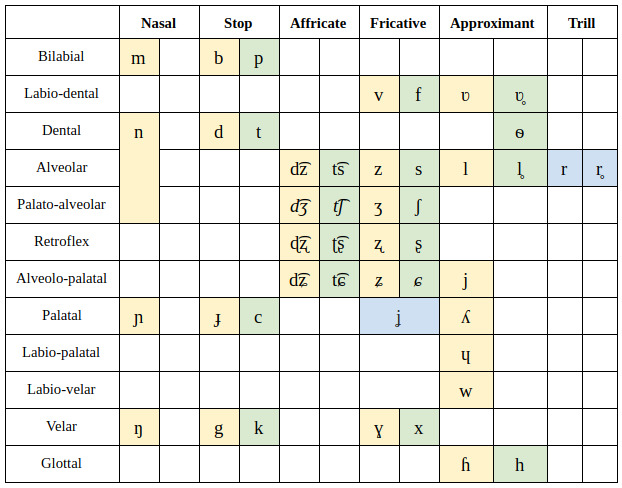

Place of the consonant can be quite different. Here are possible types: Bilabial, labiodental, dental, alveolar, postalveolar, palato-alveolar, retroflex, alveolo-palatal, palatal, labio-velar, velar. There are more types, but they do not exist in Novoslovnica.

Manner is the way how you pronounce the sound. There are also different manners, that are used in Novoslovnica. They are: nasal, stop, affricate (sibilant), sibilant fricative, non-sibilant fricative, approximant, trill, lateral approximant.

Sonority is the boolean attribute of pronunciation. You can either use your voice with the sound you pronounce or not. Notice that vowels cannot be pronounced without the use of your voice.

Combining these three parameters, we get the unique consonant that we want to pronounce. We cannot draw a 3-dimensional table, because there are three parameters on input, so we will combine information into 2-dimensional space as in paragraph about vowels. So, look at the figure and see the different consonants that are used in Novoslovnica.

Different colors of the cells show the sonority of the consonant. Yellow color shows that the sound is voiced, while green ones are for voiceless sounds.

Blue cells in the table show that sounds in it can be used both in voiced and voiceless forms as allophones.

Novoslovnica has 51 consonants, 21 of them are voiceless and 30 are voiced.

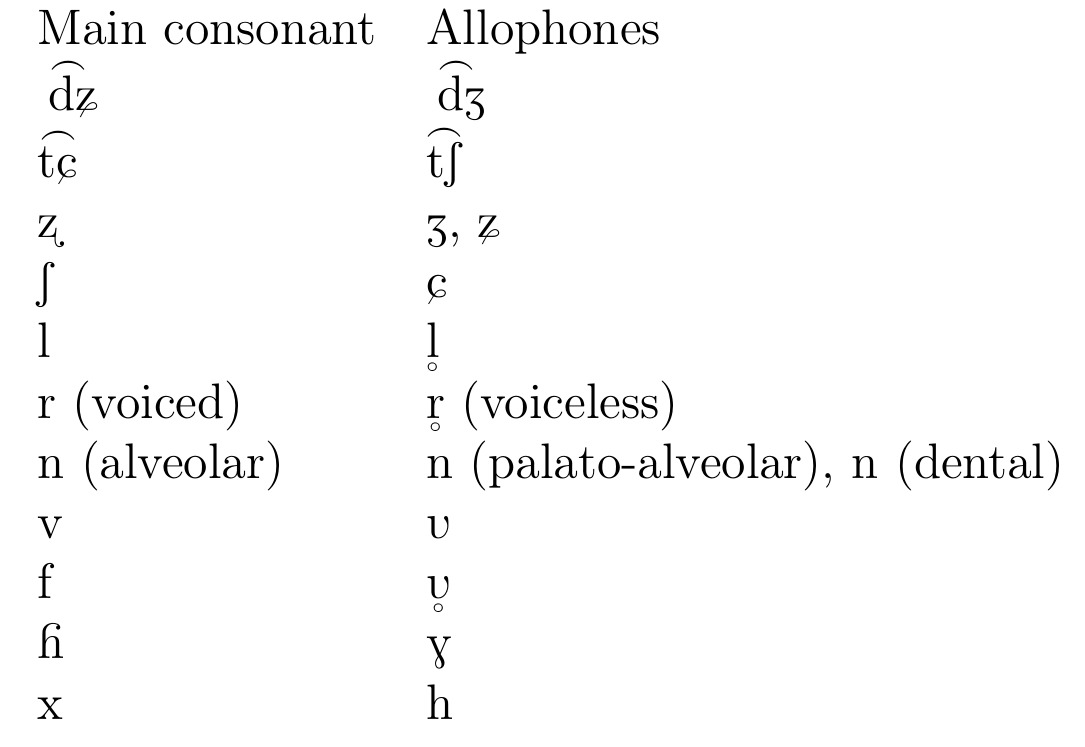

However, not all of these consonants are language phonemes. So, let’s talk about the allophones among these sounds.

Exception: The sound θ has no pair, because its pair ð has never been used in Slavic languages.

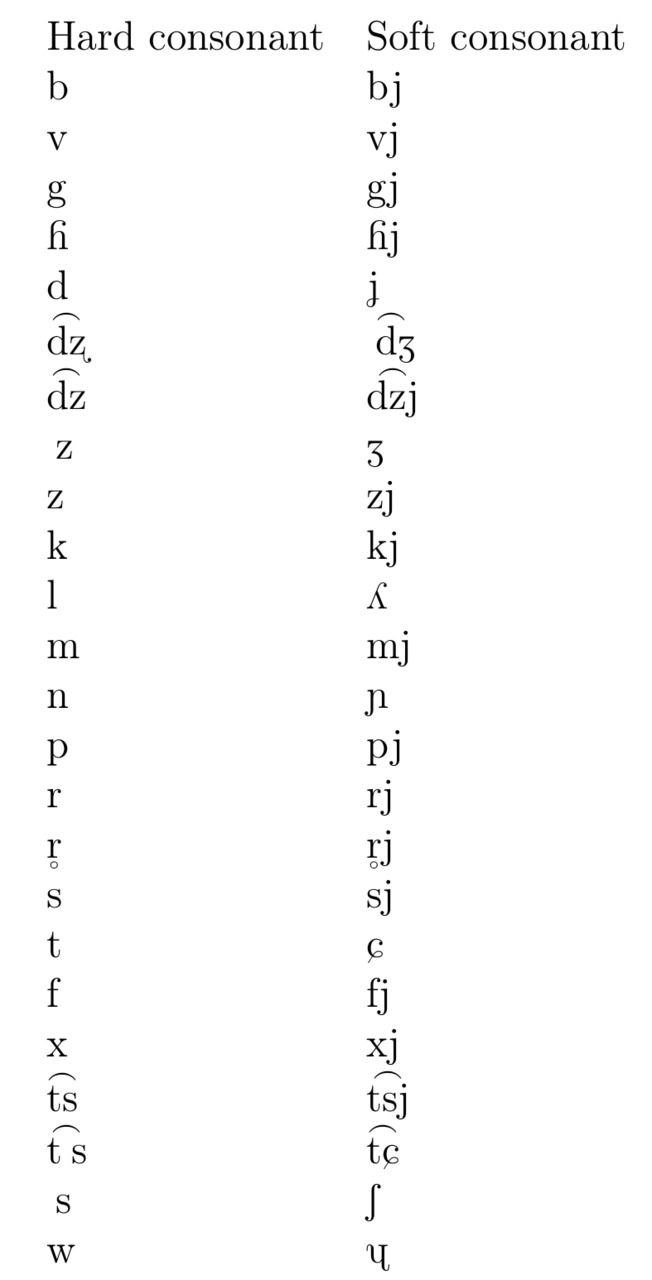

Likewise vowels, consonants can be compared with each other in terms of softness / hardness. The common rule is that every consonant has its soft or hard partner.

Exception: Two sounds are exceptions to this rule.

• Also nasal velar consonant ŋ has no soft pair.

• And vice versa, the sound j is soft and has no hard pair.

Remember this exception, let’s look at the table 1.7 to get acquainted with pairs of consonants.

As you see, every consonant from table has its own soft pair. The soft consonant is usually written as a hard consonant with the sound j attached, but some of them are provided as unique sounds by IPA, because in some languages they can be phonemes.

Extra sounds

By reading this paragraph you should be aware about Novoslovnica phonemes. At the beginning we will speak about two main features of the language: reproduction and alternation.

Reproduction (extra sounds) — is a process of adding a new sound (consonant or vowel) in the word.

Alternation — is a process of changing some sound (consonant or vowel) or sounds to another one (s).

What are the purposes of alternation and reproduction? These terms both obtain the single aim — to make our speech comfortable for ourselves.

Every language has its own comfortable combinations of sounds and avoided ones. Some languages alternate these uncomfortable character rows into another ones that are comfortable for language speaker in writing, some languages keep writing etymological and alternate the pronunciation of the uncomfortable words. Take into account the fact, that the concept of comfort is relative, that means two different languages (which are spoken by different nations) have different modes of comfort.

Example: you can look at and compare German and Dutch languages. They are very close, but they have different ways for comfortable pronunciation. The word «book» in German sounds like «Buch», but in Holland it sounds like «boek». Thus, you see that these words are familiar, but their pronunciation differs a lot.

Moreover, even one language spoken in different areas can differ greatly in the areas it is spoken.

Example: American and British English. You know that it is still the same language, but pronunciation differs so greatly that American person can not always understand in ordinary speech (quick temp of speaking) what the British person have said.

This is the example how the same language differs in areas it is spoken. Furthermore, these areas may not be far away from each other. You can find information about different patois and even dialects in very small regions.

Novoslovnica as a panslavic language absorbs different conceptions of the comfort term of Slavic languages.

When reproduction is used, we add a new sound before the word we want to say. It can be whether a vowel or a consonant, depending on the previous letter in the word.

When should we reproduce a sound? To deal with this problem, you should know a thesis, which is widely used in Novoslovnica.

Rule n. 1: After consonant there should be placed a vowel. And after a vowel there should be placed a consonant.

This rule will help you in speaking and writing, when you construct your words with the reproduction.

There is a limited row of sounds that are allowed to participate in reproduction. In the table 2.1 you can see all of them.

Examples:

osem (eight) [`osɛm] — vosem [`vosɛm]

gra (game) [ɦra]} — ïgra [i`ɦra]

So now the only problem is to know about how should we reproduce these sounds.

Reproduction of consonants can be found in different parts of the word. There are three places, where reproduction can appear — the beginning of the word, middle part of the word and the ending of the word.

When we speak about the beginning of the word, we should take into account what sound is at the end of the previous word. Due to rule 2 we should try to keep the «consonant-vowel» sequence inside our sentence. That’s why, we should do actions from the list below:

If the previous word ends with the vowel and temporal word begins also with the vowel we should add in the beginning of the word a consonant V or J. The choice of what letter to add depends on the vowel which is in the temporal word.

• We should choose J for soft vowels

• We should choose V for hard ones.

• If there is one consonant and one vowel in the set of the first letter from the temporal word and the last letter from the previous word, we should not add nothing.

Speaking about word endings, thesis 1 is also very important. We should add a letter B to the end of the word, if the next word begins with the vowel and temporal word ends with the vowel too.

As you see these two principles are practically equal, because wherever we add a consonant, the result will be the same. So the question is, when we should add to the end of the word a consonant and when we should add it to the beginning of the word. In practice, almost always we use the first case, when we add a consonant to the beginning of the word. The second case is used in prepositional constructions with such a word as «O» (about) (Look: «O» — «Ob»). In other cases try to use letters V and J for reproduction.

The third case of consonant reproduction is to reproduce it in the middle of the word. It is used, when there is a row of vowels in the word and it is difficult to pronounce them all together. Then you can divide them by the consonant J, which is put between the neighbor vowels. Don’t confuse it with the case, when with the addition of a vowel letter Ǐ transforms to letter J (see the next paragraph for it) and you receive to vowels divided by this consonant two. Look at the examples of consonant reproduction in the middle of the word.

Examples:

ïdiot (idiot) [`idɪot] — ïdijot [`idɪʝot]

The same situation is about vowel reconstruction. You can find it in the beginning, in the middle and in the end of the word, but it is a bit simpler than a previous one. Vowel reproduction appears when there is a rather large amount of consonants in one place of the sentence. This means that you can find a row of consonants in the word or a consonant conjunction in the end of one word and in the beginning of the next one. In any case, you should concern here about whether it is comfortable for you to pronounce these combinations of sounds.

In the beginning of the word we add a vowel Ï and there are no other cases. Very simple.

Examples:

gra (game) [ɦra]} — ïgra [i`ɦra]

In the middle or in the end of the word we add a vowel O. This case is used with prepositions and prefixes («K» — «Ko», «S» — «So» etc).

Examples:

k domu (to home) [k `domu] — ko dvoru [ko `dvoru]

Alternation

Alternation is a very important feature of Slavic languages. All of them provide some cases, when one letter changes to another one (s) and controversially. The cause is the fact that some sound combinations are difficult to be spoken or not comfortable for that. For example, Slavs can say «napisati» (to write), but «napišut» (they (will) write). The variant «napisut» is not comfortable to pronounce and, moreover, it is not understandable. What are you speaking — «to write» with hardened T or «they write» with depalatalized S. So you can see, that these rules are often experimental and cannot be explained in a common way.

Alternation can be found mostly in conjugation or declension of the word, because the process is in changing uncomfortable forms to better ones while changing the base and endings of the word.

In this paragraph we will speak about different examples of vowel and consonant palatalization. Let us begin with the consonants.

Alternation S//Š

This alteration appears in words with the letter S before a vowel A. The basic sound is S, which changes to Š before vowels I, E and in some cases before A in conjugation. Let’s look at examples to understand how it works.

Examples:

Pisati (write) [`pɪsatɪ] — piši [pɪ`ʂɪ]

Vysok (tall) [vɨ`sok] — povyšati [po`vɨʂatɪ] (to increase)

Alternation K//Č

This alteration appears in words with the letter K before a vowel A without a following vowel. The basic sound is K, which changes to Č before vowels Ě, N. Let us look at examples to understand how it works.

Examples:

Věk [vek] — věčen [`vet̠ʃɛn]}

Vëlïk [`ve̞lik] (Big) — vëlïčina [`ve̞lit̠ʃɪna] (Measure)

Alternation C//Č

This alteration appears in words with the letter C before a vowel A. The basic sound is C, which changes to Č before vowels I, E. Let us look at examples.

Examples:

Ptica (bird) [`ptɪtsa] — ptičen (birdish) [`ptɪt̠ʃɛn]

Věnec [`venɛts] (Crown) — Věnčati [`vent̠ʃatɪ] (To crown)

Alternation D//Đ

This one appears in words with the letter D before a vowel I. This consonant changes to Đ before vowels A, E and U. Let us look at the examples.

Examples:

Voditi (drive) [`vodɪtɪ] — vođati [`voɖʐatɪ]

Roditi [`rodɪtɪ] (bare) — rođati [`roɖʐatɪ]

Alternation Ǐ//J

This alternation is very simple. We write Ǐ before a consonant or in the end of the word and we write J before a vowel. The exception is the case, when we write Ǐ in the end of the word, but the first letter of the next word is a vowel — then we pronounce J, but write Ǐ.

Examples:

Môǐ (my) [mʊj] — moja [`moʝa]

However, not only consonants can change in the word when we conjugate or decline it. There are some alterations of vowels too.

Alternation Ò//-

This alternation appears in some old roots (see next paragraph).

Examples:

Tòk (stick) [tək] — tkati [`tkatɪ] (to weave)

Alternation E//-

This alternation is similar to the previous ones, but exist in word suffixes.

Examples:

Krasen (Nice) [`krasɛn] — krasna [`krasna]

Alternation Ę//En

This alternation is rather narrow, because it is used in the case of declension nouns of type 3 (look paragraph about noun declension), when the nasal vowel [ɛ̃] alternates to non-nasal pair of vowel «E» and consonant «N» (non-nasal!). To understand it look at the example

Examples:

Vremę (time) [`vrɛmjɛ̃] — vremenï [`vrɛmɛɲi]

Plemę (tribe) [`plEmjɛ̃] — plemenï [`plɛmɛɲi]

In the conclusion of this paragraph it should be mentioned that alterations are very important in Slavic languages and Novoslovnica as well. You can use reproduction in your speech as a recommended feature, while alterations are complimentary in this language. As it was noted before, we cannot ignore anything that can bring a misunderstanding in our speech.

Runaway vowels

Looking back in the Slavic language history we can find out that there were roots with two strange for an ordinary person vowels — «Ò» and «J». First one was named «Yer» and denotes a hard mid central vowel (Shwa). The second one was named «Yerj» (with soft R) and denotes a soft mid central vowel. Now the second one is lost and we use only shwa sound in the letter «Yer». However, the words are still and we need to pronounce them in some way. Novoslovnica uses the soft «E» sound to represent roots with old soft shwa sound.

Main feature of these sounds was to fall out from the root, when a vowel appears afterwards. That’s why there are many words with two consonants consecutively — there is an imaginary shwa sound between them that has been fallen out from the root.

Nevertheless, despite falling out of «Yer», soft «E» in this places does not fall out. So, in the previous paragraph you could see that there are two alternations O//- and O//Ë, that are handled in the similar positions. So the answer on the question, why in the first case there is no sound and in the second there is a soft E is the fact, that words satisfying the first case comprise old hard shwa sound and remain comprise old soft shwa sound, that has transformed into soft E.

The fact should be mentioned that nowadays the letter Ò exists only in roots of the words. In suffixes the letter E is used for this sound and in the prefixes the letter O is used.

Look at the examples:

— pod

— ek

— pòk

However, you should remember that speaking the words with these letters we should pronounce them just as they are written — Ò as shwa, E as E, O as O. You should not reduce all the sounds to shwa.

Accent

Accent is a very difficult topic in most languages, because it is not permanent. There are some exceptions i.e. Czech and French, but in most cases we cannot say where accent will be put in the word without studying definite language. This causes problems for beginners.

Novoslovnica has a dynamic accent, but it has been formalized. There is a rule, that determines the place you should put the accent.

Rule n. 2: The accent should be put on the first syllable of the word root.

This rule covers about 80% of the words in the lexicon. You know the well-known 80/20 rule, or Pareto principle. It is something alike with the accent. Remained 20 per cent of the words we should cover by introducing extra-rule cases. Accepting these cases, you will be able to cover more than 99 per cent of Novoslovnica word amount.

These cases were created in attempt to unify the accents in different Slavic languages. Surely the Slavic languages have greatly changed since then, as they were one language. Therefore, accents in different Slavic languages often differ. Nevertheless, Novoslovnica tries to obliterate differences between them, producing accent patterns that could be comfortable to pronounce and to hear for all Slavs.

Below you can see the list of all these cases, that you should remember while speaking Novoslovnica.

Accent shifting cases:

— Accented endings (Nouns)

• -a (Dual, Nominative)

• -y (Singular, Genitive/Partitive)

• -ami (Plural, Instrumentative)

• -ama (Dual, Dative)

• -am (Plural, Dative)

— Accented endings (Verbs)

• -i Imperative (see paragraph about verb moods)

— Accented suffixes

• -ova- (Verb)

• -ôva- (Verb)

• -ava- (Verb)

• -óv- (Adjective)

• -ak- (Noun)

• -ok- (Noun)

— verb suffixes in Present Concrete Tense (see paragraph about verb tenses)

— Accent shift in the root

• If the word is a borrowed one, then the accent is put on the place it is in the original word.

• If the root loses its vowel, the accents moves one vowel to the left (if it is possible)

• Words that have more than one root (complex words) have their accent on the first syllable of the main word’s root. (see paragraph about complex words for what root is main)

• Adverbs or other parts of speech, formed with the prepositional construction, have their accents on the first syllable of the main word (see paragraph about collocations)

These rules are enough for you to speak Novoslovnica properly with a few efforts for it.

Accent integrity

There is also one term, that you should to know when you use Novoslovnica or any other Slavic language in your speech. This term is called accent integrity. Firstly I will introduce a term of a dependency structure:

Dependency structure is a prepositional construction or a collocation.

That means, that this abstract term expands the term of collocation by involving prepositional into itself.

Accent integrity is a property of a dependency structure to unify elements of this structure with only one accent on the main word.

What does this definition say? If we have a collocation\index {collocation} or a prepositional construction and we want to pronounce it, we should pronounce dependent words without any accent and put an accent on the first word of the structure. Look at the examples.

Examples:

Pod něbom [`pod nebom] — Under the sky

Surely, you should remember that this might be applied only for brief structures, most often with one dependent word (or a preposition) of one or two syllables. If we have a long dependent word or there are too many dependent words in the construction, we pronounce them with a proper accent on each of the structure elements.

Examples:

Pod sïnïm něbom [pəd `sinim `nebom] — Under the blue sky

Orthography

Alphabet

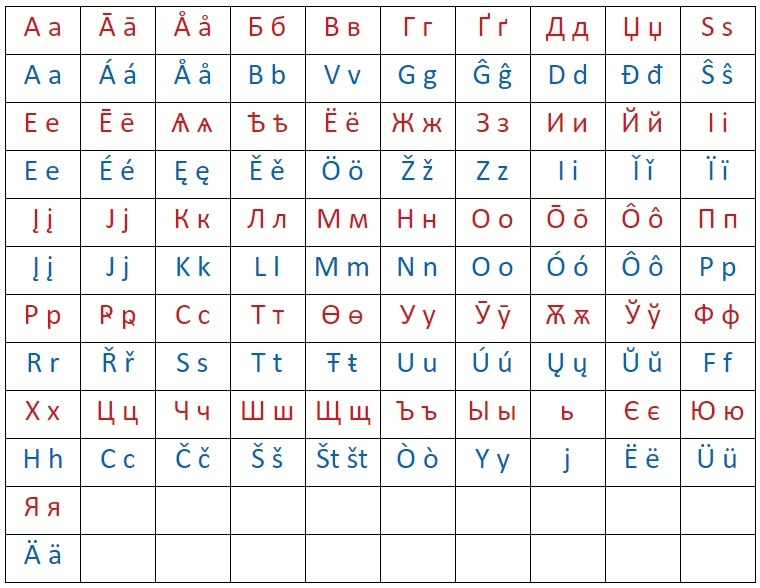

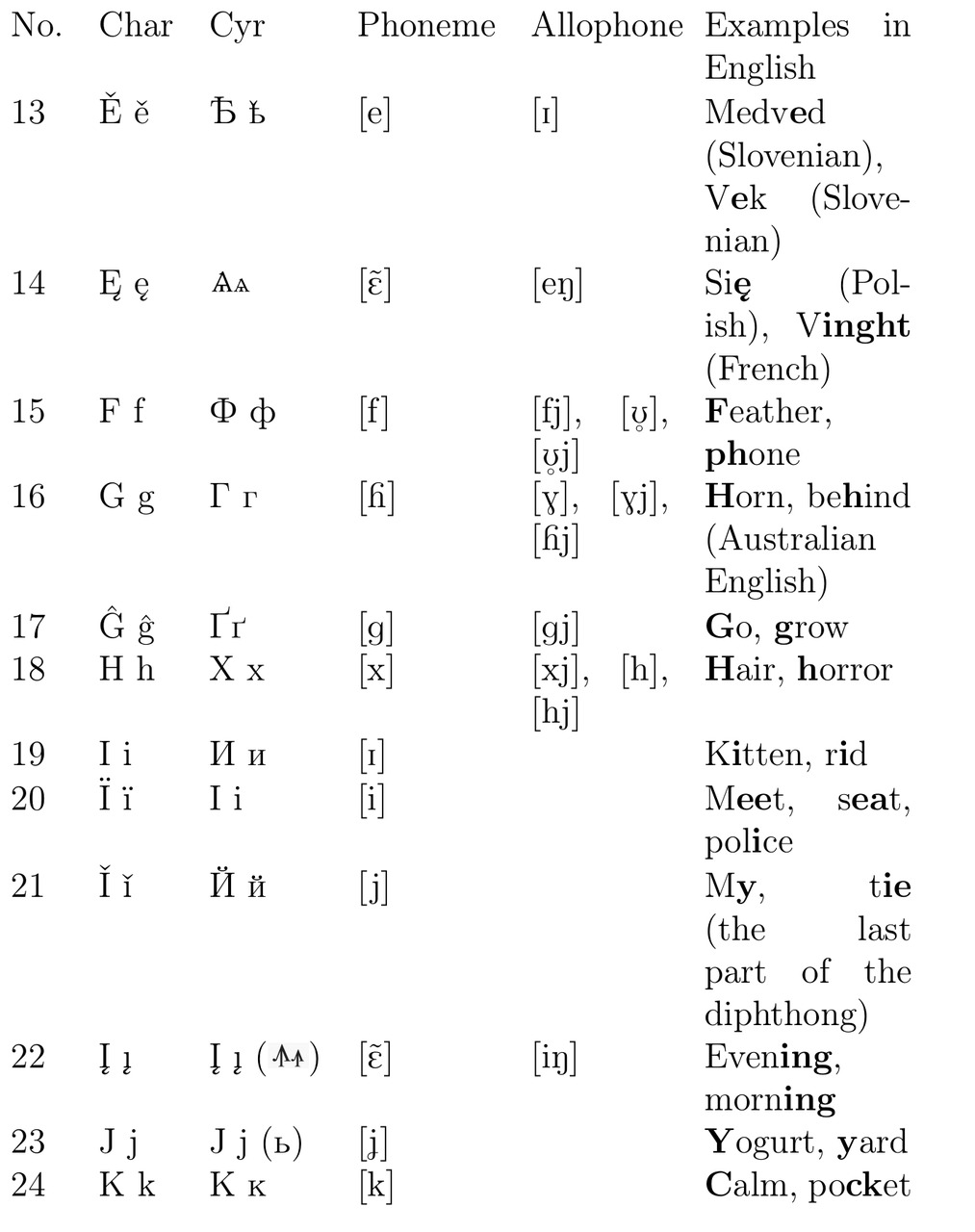

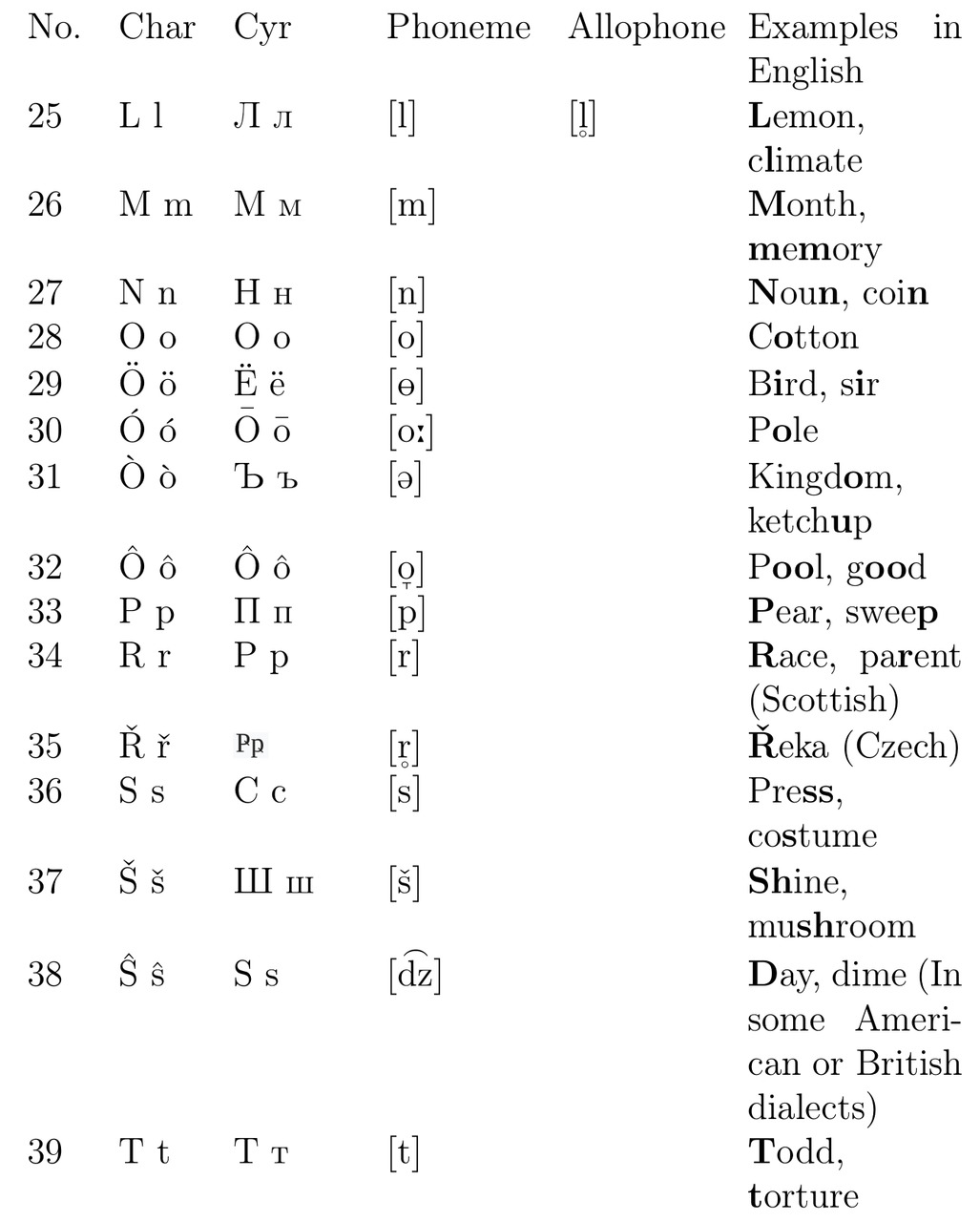

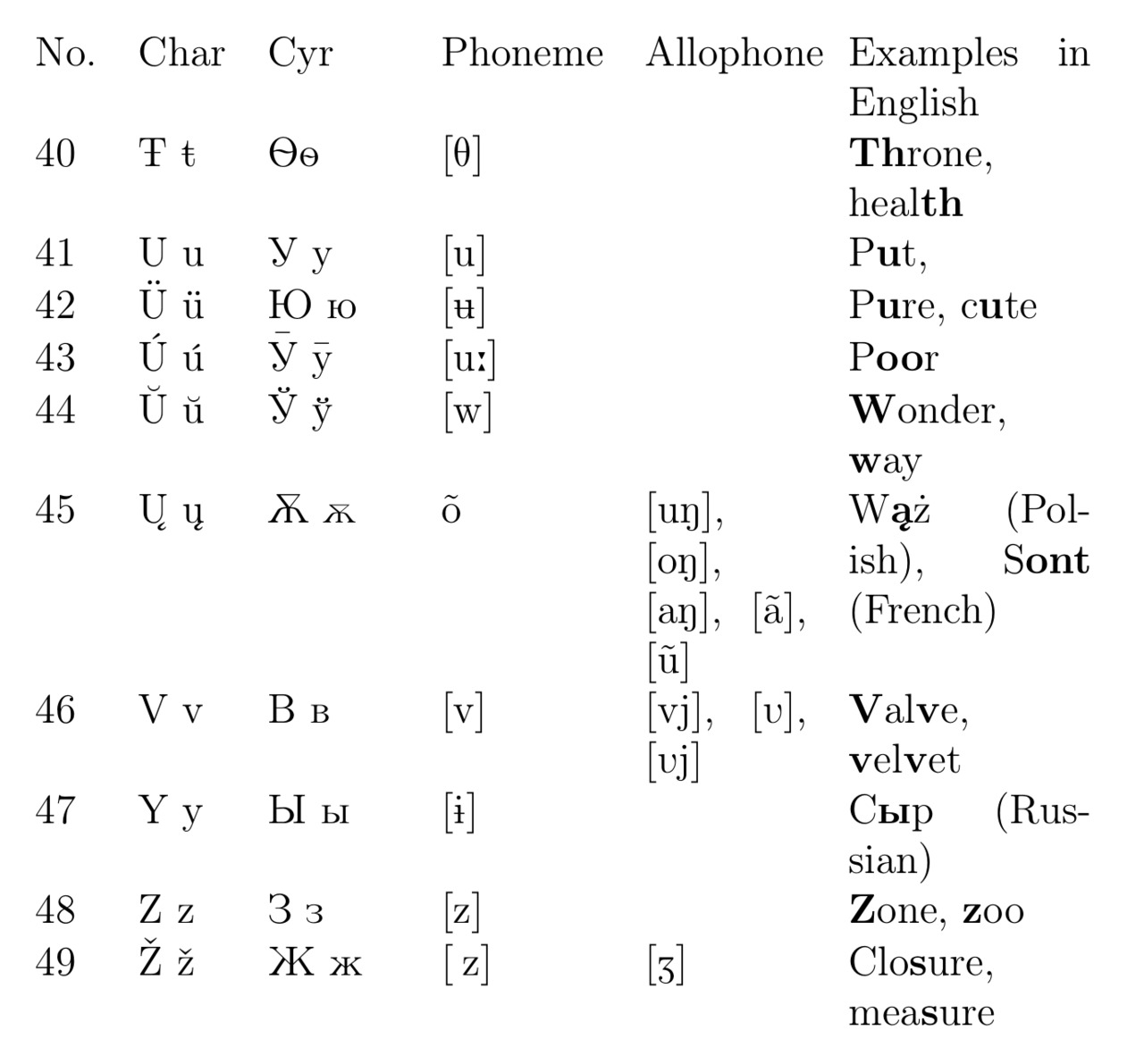

Let’s summarize what we have known about Novoslovnica phonology. Afterwards we will get the list of phonemes and allophones and their connections with Novoslovnica letters in the alphabet.

We have learned that Novoslovnica has 51 consonant sounds and 22 vowels. 13 consonants and 4 vowels are allophones among them. Hence, the amount of phonemes is (51—13) + (22 — 4) = 56 phonemes.

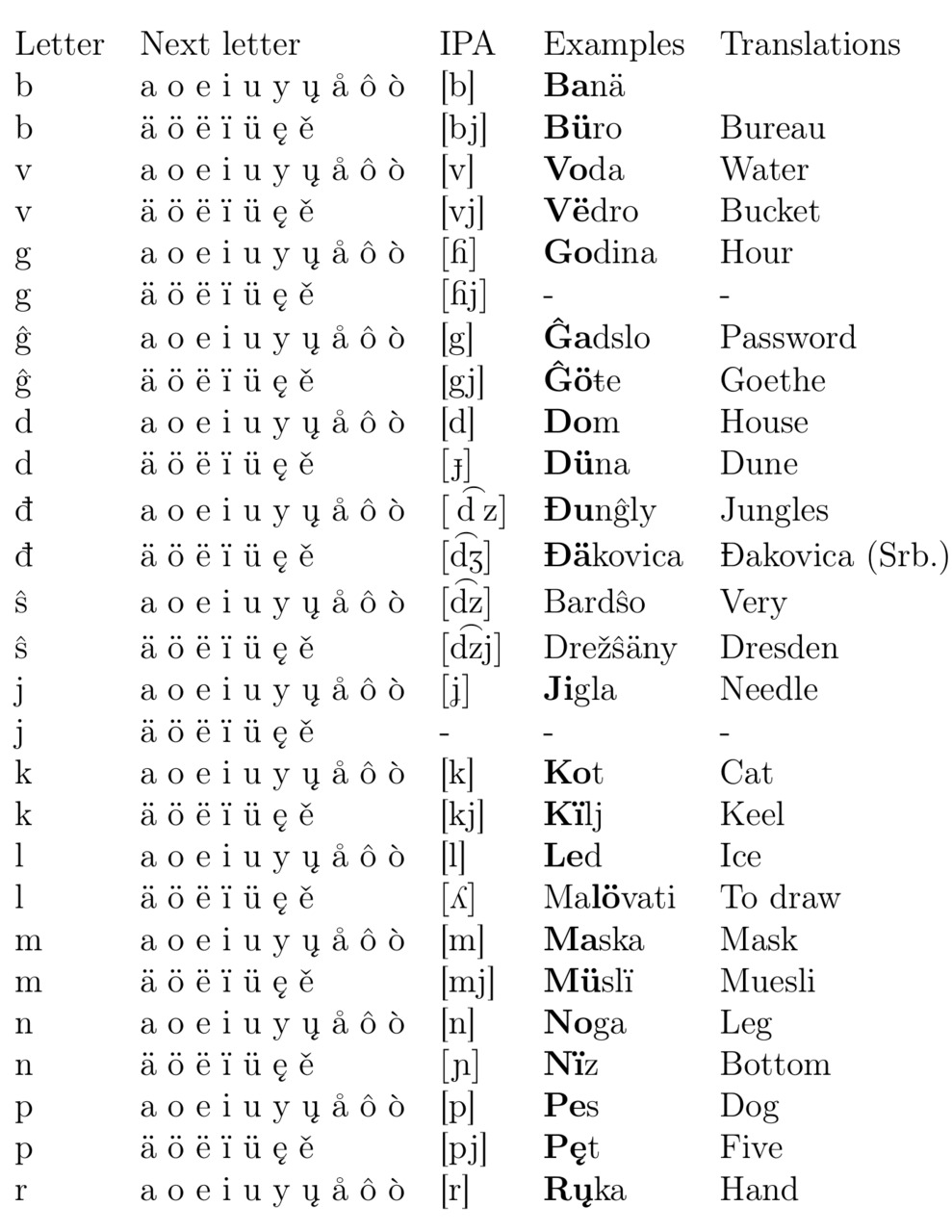

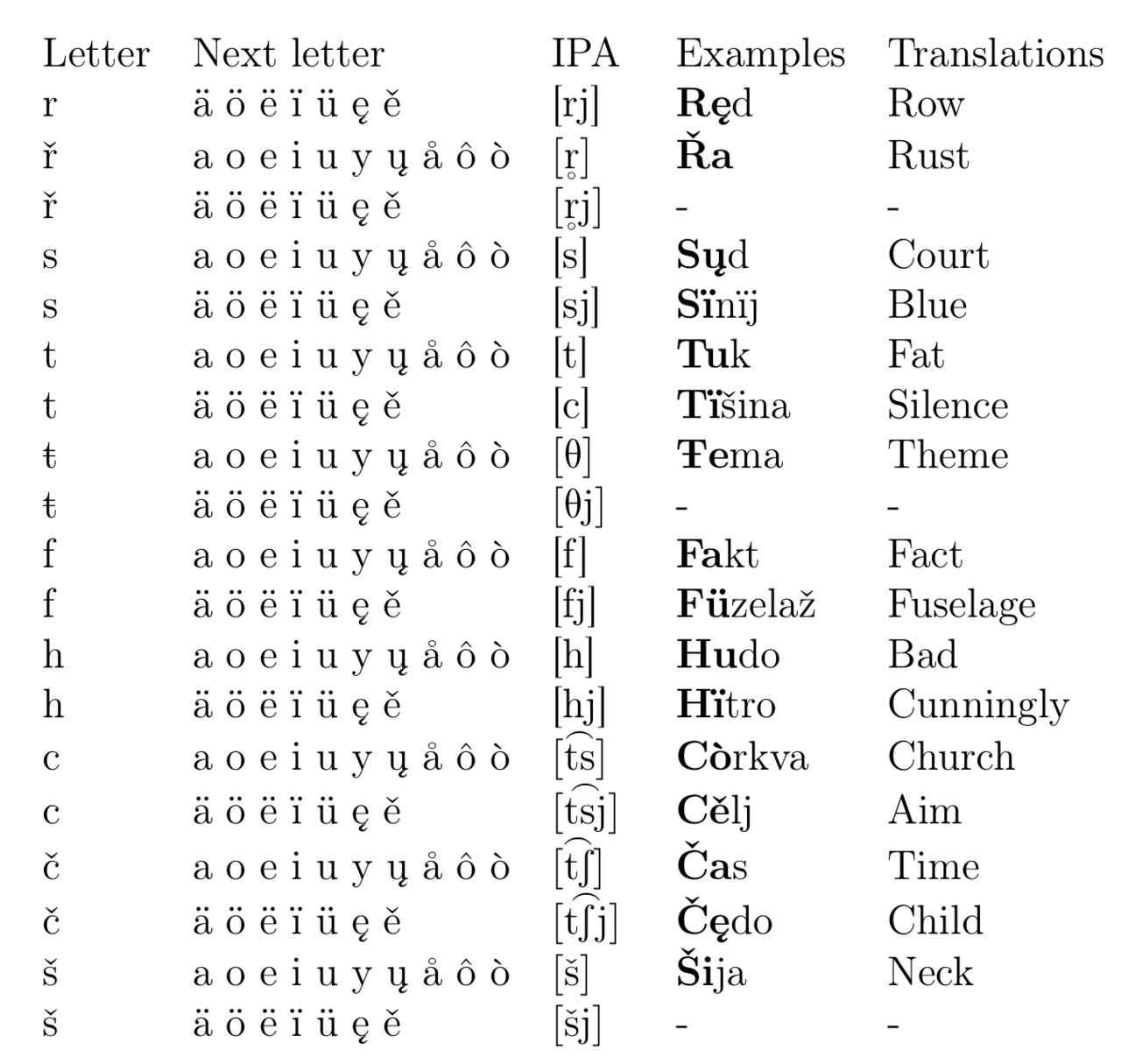

You should know that in Novoslovnica, soft and hard consonants do not differ in writing. That is because of the fact that by the combination of «consonant + vowel» we can always determinedly get what the consonant is like — hard or soft. With this information, the amount of letters needed is reduced to 49.

Nevertheless, let’s now look at the table with the alphabet list and see how Novoslovnica is written.

Note, that the Cyrillic letters Щ, Ψ, Ќ, Ї in earlier versions of Novoslovnica have been replaced by Шт (Št), Пс (Ps), Кс (Ks) and Ји (Jі).

Cyrillic has two different letters Ь and J that have different functions — the first one defines that the previous consonant is soft (in case vowel is absent) and the second defines a [ʝ] sound. Latin version that you see in the table has no such a difference, so you should remember, that J means a soft sign when you see a C-“J”-C row (where C is for “Consonant”) and means a [ʝ] sound when you see a C-“J”-V (where V is for “Vowel”), or use Cyrillic to prevent such a collision. Only in the first case the consonant before J is soft while in the second one it is hard.

Pronunciation

Novoslovnica is a phonetic language, that’s why Novoslovnica has an important rule, which you have to apply to speaking in Novoslovnica.

Rule n. 3: All words are pronounced as they are written.

This rule means that you cannot reduce sounds when speak in Novoslovnica. It is a very important thing because you can make mistakes if you speak improperly. There are some exceptions but they all will be mentioned in this guidebook.

When you pronounce a word you are not restricted to use only main sounds — if it’s more comfortable, you can pronounce allophones with the same level of softness and sonority with the main sound of the letter. Let’s look at the examples below to understand what we can choose in speaking and what we cannot.

Examples:

— okolo [o`kolo] — around

— čujstvo [`t̠ʃujstvo] — feeling

However, you are restricted in what consonant sounds to use from the allophone list. You can see the next rule which will help you to speak.

Rule n. 4: You cannot mess soft and hard consonants when you pronounce a word.

This prohibit you to make hard consonants when you need a soft one, or to use a soft one when you need a hard one. Here you can see a table, where it is shown which sound you must pronounce in different combinations of letters.

Some features

I and Ï

Many people will surely be confused by these two letters. They will ask whether there is the rule when we need to write the first ot the second one. However, you should look up and remember that these both letters produce different sounds. And that is the point.

The first letter produces the soft sound «I» while the second one stands for the hard sound. But the question is, where are used such sounds? We can’t list the rules for usage these letters in the root, because it is an etymological issue. However, we can list some prefixes and suffixes that contain either a soft or a hard letter.

Marks for writing «I»:

Prefixes

— Iz

Suffixes

— Nic

— Nik

— Itelj

— I

Conjunction

— I

— Ili

— Či

— Li

Marks for writing «Ï»:

Prefixes

— Nïz

Suffixes

— Ïc (female animals)

Latin and Cyrillic

You can see in table 1.8 that Novoslovnica utilizes two alphabets- the Latin one and the Cyrillic one. They both are practically equal, but is there is a preferred alphabet for the language? The answer is «yes», Cyrillic is preferable.

The reasons of choosing such a script goes back in history. There were two scripts in the beginning of Slavic writing: the Glagolitic and Cyrillic scripts. They were created to cover all the sounds that existed in that era of Slavic languages. Glagolitic script practically has no borrowed letters from other writing systems- all letters are unique.

By this case in Cyrillic and Glagolitic scripts we can find the bijective mapping between sounds (phonemes) and letters. Latin script does not provide such orthography in any Slavic language which uses the Latin script.

For example:

— «ch» for [x], while «c» is for [ts] and h is for [x]

— «sz» for [ʂ], while «s» is for [s] and «z» is for [z]

Novoslovnica provides an artificial Latin script system, where the bijective mapping has almost been achieved. The Latin alphabet can seem strange or uncomfortable to native Slavs (though it can be used rather conveniently by non-Slavs). That’s why the Glagolitic or Cyrillic script should be used primarily.

Why hasn’t the Glagolitic script been mentioned yet? The same reason that the Latin script should not be used primarily: to prevent misunderstanding. Nowadays only one in a hundred Slavs can understand the Glagolitic script because all of its letters are original. That’s why this language, which has the goal of being used on the international level, cannot use Glagolitic script as its primary script.

The only script, that satisfies all the requirements to be the primary script of this Slavic constructed language, is the Cyrillic alphabet. In this book you will find many examples in different paragraphs. First you will see a primary (Cyrillic) variant of the example in normal font and then a Latin one in grey italic font. This will help you to learn primary script of Novoslovnica quickly. Nevertheless, if we speak about exact letters or letter combinations, I will write them only in Latin for not to mess the text of the book.

Now you know the sounds and the letters which are used in Novoslovnica and you are ready to go deeper!

Grammar

Grammar is the core of every language. Grammar comprises different themes that are united in a system of changing words enough to build sensible syntax constructions. We will look at Novoslovnica grammar from the point of the parts of speech.

Part of speech (POS) — is a category of words which have similar grammatical properties.

Thus, we unite a group of words into parts of speech when they have a lot of similar grammar properties such as «number», «person», «case», «tense» etc. In this chapter we will go through different parts of speech and study what differences they have and how we should identify each of them and combine them to be able of creating phrases and sentences.

Parts of speech comprise two main categories — independent POS and auxiliary POS. The fact the POS is independent or not refers to its semantic value. An independent POS has a full semantic value that can be used separately. That means when you say a word of an independent POS you reproduce some semantic meaning that the interlocutor can recognize. An auxiliary POS a semantic value that is partially defined and can be distinguished only in pair with a word of an independent POS.

Example:

River — this word can be recognized by interlocutor as some concept of water flowing in a restricted area.

Beautiful — this word is recognized as an attribute of any concept that is nice, pleasant to the person (i.e. speaker or interlocutor)

Came — this word can be recognized as any concept’s action of going to the destination point and having reached it.

And so on. Nouns, adjectives, verbs, adverbs, participles, numerals, pronouns refer to independent POS. You see that every word has its own meaning full enough to imagine yourself some information you have received. This is not true for a word of an auxiliary POS.

On — this word can be recognized as a placement of an object against some horizontal surface. It can refer to some time moment (be on time). It can also be used with a fully different value (come on — to increase the activity of doing something).

For — it can be recognized as an aim for something or an object that participates in some action. Also this word can refer to a duration of a process.

Moreover, words «and» or «to» cannot give you any map in your mind into any sensible meanings. Though these words have no determined semantic value, they are extremely important in the whole phrase connecting two words of the same POS with logical value (AND, OR, NOT). English language is an analytical one, that is why words are mostly connected with each other in the phrase by an auxiliary POS. Without them you are not able to understand what the person is speaking about. Slavic languages are fusional, however, there are enough analytic features in them, hence auxiliary parts of speech are also important. Articles, prepositions and conjunctions are referred to auxiliary parts of speech.

There are also two additional categories — particles and interjections. Some allocate them into separate categories, some claim they belong to an auxiliary category. Nevertheless, these are both separated parts of speech because they have different grammar properties.

These are all categories of POS. If we speak about an independent POS, we should take into account that there are different semantic, morphological and syntax functions can be described by it. There are several types of semantic functions: the concept, the attribute, the predicate and the demonstrative.

The concept is something that correlates with the object or subject in the real world. It could be either abstract or imaginary, but we can ask a questions «Who? What?» about it.

The predicate is something that determines the action, corresponding to a concept. We often ask questions «What to do?» to reveal a predicate.

The attribute is something that is correspond to a concept or an action. We ask questions «What concept is like?» or «What action is like?» to find out the determine value of the attribute.

The demonstrative points out the concept. It has the same question with the attribute yet has no semantic value but demonstrating the concept it corresponds with.

— Reducing verbal suffix "-a-», «-e-» etc.) and adding null-ending. These nouns will be of the second declension.

Parts of speech that have properties of an attribute are: adjectives, participles, ordinal numerals and adverbs.

Parts of speech that have properties of a predicate are: verbs, transgressive, and gerund.

Parts of speech that have demonstrative properties are most kinds of pronouns.

Thus, noun, adjective, verb, adverb, numeral, pronoun, gerund and participle are independent POSes, while preposition, particle, interjection (with Onomatopoetic), article and conjunction are auxiliary ones.

Independent parts of speech are also divided into nominal and verbal ones. It is extremely important because this division shows differences in grammar forms of nominal and verbal POS. Verb, participle, transgressive, gerund are verbal parts of speech, while noun, adjective, numeral are nominal. Adverb and pronoun stay separately — the first one because of its immutability and the second one because of its heterogenity.

In the chapter it will be spoken about the very POS exists in Novoslovnica. The table with grammar and semantic properties of a POS will be given in the corresponding section.

First of all you should know some facts about different grammatical properties in Novoslovnica.

Cases

Case is a grammatical property of a nominal POS (Part of speech) that shows what references this nominal POS has with other words in a sentence (phrase). This property is widely known in fusional languages, while analytical languages do not often possess this property. Thus, English has only two active cases — Nominative and Oblique one. Moreover, oblique case is used practically only within pronouns while nouns have no such a case. That means case is not the only way to show references between nominal POS and other words in a sentence. Case is just one of the ways to show it and Slavic languages as being fusional widely use this grammar category.

Different Slavic languages have different number of cases. For example, Russian language has six cases while Serbian language has seven. We can find exceptions in Bulgarian and Macedonian languages, which are analytical that is why they have only one case for a noun and adjective and three cases for a pronoun.

Different cases are referred to different semantic links between words. It is the cause why we see ambiguity of cases in different languages (that have different amount of cases and different usage rules of cases). Novoslovnica provides most common and wide means to use cases with almost full determination. When you speak Novoslovnica you have to use the case of exact semantic value and not of the longstanding phraseology of your own language.

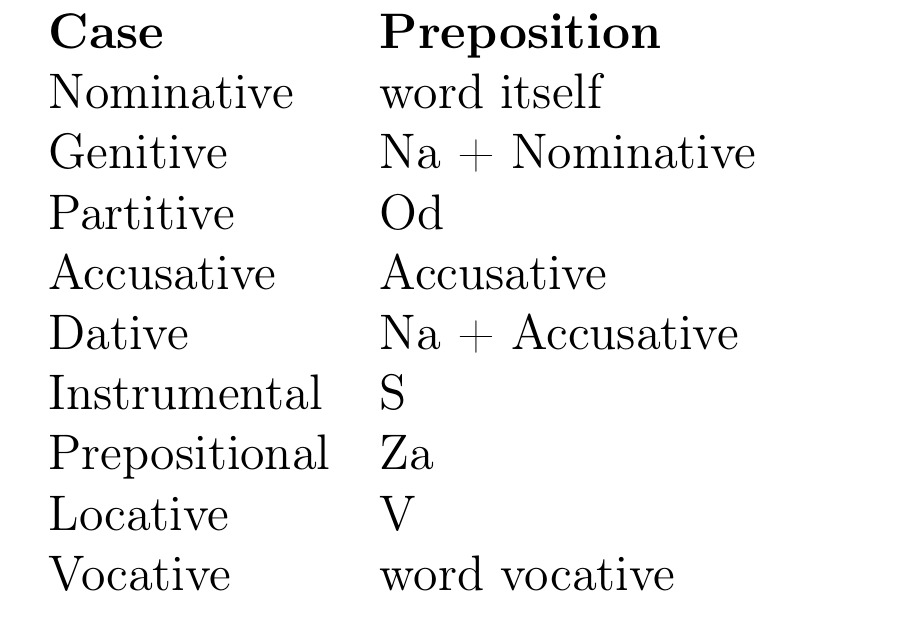

With this principle Novoslovnica establishes nine cases. Nine changing patterns that determine alterations of all words of nominal POS. This is the unification of Slavic languages in the sphrere of fusial word linking. Here they are:

— Nominative (N.C.)

— Genitive (G.C.)

— Partitive (P.C.)

— Dative (D.C.)

— Accusative (A.C.)

— Instrumental (I.C.)

— Prepositional (Pr. C.)

— Locative (L.C.})

— Vocative (V.C.)

In this chapter we will speak about cases in general. All examples will disclose case features through nouns as examples.

Nominative case (Imenóvnik} is used when we are talking about a concept as an actor. If the sentence is full, the subject is in Nominative. You can ask questions like «Who? What?» to it.

This case is basic in most languages, so POSes in this case are supposed to be in the normal form (that we can find in a dictionary). In Novoslovnica nominative also determines a normal from of the word. In the examples you can see full sentenses, where subject is used in nominative.

Examples:

— Dom-òt je vëlïkym. — The house is big.

— Izučilišto, de ja sę učam, je starym. — The school I attend is old.

— Klüč-òt je od ovoŭ vråtoŭ. — The key is to these doors.

Genitive case (Čyǐnik) is used when we are talking to an object being related to another one. Thus this case show what generation the object is of and what is it made from or whom does it belong to. The questions that determine the case are «Whose? Which? What?».

In Novoslovnica possessive case equals to genitive one, so English «’s» constructions should be translated in genitive (example 4.1.4). Further, genitive in Novoslovnica could be related to usage of nouns with «of» preposition (example 2, 3).

Examples:

— Kniga brata je vëlïmi zajimliva. — My brother’s book is very fascinating.

— Cěna uspěha je mnogo vëlïka. — The price of success is very high.

— Sklad je na koncu ulicy-ta. — The shop is at the end of the street.

Partitive case (Ličóvnik) is used when we are talking about some amount of object having or being supposed to have uncountable properties. The questions that determine the case are «Of what? With what? How much of?».

This case has many coinciding forms with genitive, though in masculine gender it has another endings (examples 1, 3). In English it should be translated with «of» construction (example 1). If uncountable nouns are used with the predicate directly or with adverbs of measure, they should be translated into Oblique case in English (example 2, 3).

Examples:

— Daǐ mi čašku čaju. — Give me a cup of tea.

— Dodaǐ do pïroga němnogo vody. — Add some water to a cake.

— Predaǐ mi cukru. — Pass me sugar.

Dative case (Datelnik} is used when we are talking about a noun to which something is given. We can ask a question for a word in this case as «Whom? For whom?».

It’s simple with pronouns, because there is a dative case within pronouns in English (example 1). In some use cases we can find a noun with «for» preposition to be translated into Novoslovnica’s dative (example 2). However, in these cases form with «dlä» preposition with genitive can be used instead (example 3).

However, there are cases when some direct objects in English will be translated with dative in Novoslovnica (example 4), so you need to consider the semantic value of dative — give somebody something.

Examples:

— Kaži mi, čto ty hteš da dostęžiš ovym. — Tell me what do you want to achieve with this.

— Jesòm stvoril podarek tatě. — I’ve made a present for daddy.

— Jesóm stvoril podarek dlä taty. — I’ve made a present for daddy.

— Jesòm podal bratu moju pomočj, dy on zapytaše mę o tom. — I helped my brother, when he asked about it.

Accusative case (Vinitelnik) is used to describe a direct object of the action. The questions determining the case are «What? Whom?».

If a noun has a role of a direct object in English sentense (Oblique case), you should translate it with accusative in Novoslovnica (example 1—3).

Examples:

— Ja viđu lěpyǐ lěs predò mnom. — I see a beautiful forest ahead of me.

— On pokazaše mi kota, ke glåsisto kričěše. — He showed me a cat, crying loudly.

— Znaš li ty rěku, če tëče z severu na jug? — Do you know a river that flows from north to south?

Instrumental case (Tvornik) is used to describe an instrument of an action that affects the object of the action. The questions related with this case are: «With whom? With what?».

As you can see from auxiliary questions, English phrases with «with» expressions should be translated to instrumental case in Novoslovnica. Moreover, «by» expressions also are translated to instrumental case. The difference is in preposition:

— «with» -expressions are translated in

• «s»+instrumental case (keeping preposition) with animate nouns or pronouns (examples 1, 2)

• instrumental case (loosing preposition) with inanimate nouns (example 4)

— «by» -expressions are translated in

• instrumental case, loosing preposition (example 3)

Examples:

— Idaǐ na věčôrku sò mnom. — Let’s go to the party with me.

— Kaži mi, s kym ty hteš poǐdati na věčôrku? — Tell me, with whom do you want to go to the party?

— Kniga-ta je napisana vëlïkym tvorcom. — The book is written by a great author.

— Ta búda je vybúdana kamenom. — That building is built with stone.

Prepositional case (Predložnik) is used when something is an object of speaking. It can be related to auxiliary questions «About what? About whom?».

In English there are two prepositions that show that it should be translated to prepositional case in Novoslovnica — «about», «of». Note, that you should divide phrases with the object of speaking from phrases with genitive forms.

This case is called prepositional in Novoslovnica, because it is used only with preposition «o» (about).

Examples:

— Råzkaži mi o tom slučajě. — Tell me about that case.

— On ne zna ničto o tom městě. — He knows nothing about that place.

— Ja ne kazal sòm mu ničto o sobě. — I have told nothing to him about myself.

Locative case (Městnik) is used when we speak about something as a place where the action related with the predicate takes place. It can be related to an auxiliary question: «where?».

In English phrases with both «at» and «in» prepositions should be translated to locative in Novoslovnica (examples 1—3). Note, that «in» preposition is usually translated with locative, while «into» preposition should be translated with accusative (example 4).

Examples:

— Hođu v lěsu. — I am walking in the forest.

— Ja běše v domu, koĝda ty pozovaše mę izvòn. — I was at home, when you called me out.

— On živa v golěmomu grådu. — He lives in a big city.

— Hođu v lěs. — I am walking into the forest.

Vocative case (Zvatelnik) is a special case in Novoslovnica that binds a new object to the action by direct mentioning it.

Vocative is usually used with human names (example 1) or animate nouns (example 2), but can also be used with every noun that is supposed to be a receiver of an action result (example 3).

Vocative is usually divided from the main sentense by a comma.

Examples:

— Ivane, začto ne odgovořaš mi? — Ivan, why don’t you answer me?

— Otče, koĝda hte mi kupiš dvojokol? — Father, when will you buy me a bike?

— Větre, začto ne sę zaspokojiš? — The Wind, why don’t you calm down?

These cases cover 99,99% of possible nominal POS declension. Some extra ordinary cases exist, but they should not be mentioned here.

Analytical declension

Bulgarian and Macedonian languages involved a non-synthetic declension to our Slavic languages. Thus, we can use prepositions instead of cases to express the connections between words in a NP. In the following table you can see the correspondence between cases in Novoslovnica and the prepositions that are able to express the same connection.

Examples:

Čaška od čaǐ — Čaška čaju — A cup of tea

Dati kniga na Natašu — Dati Natašě knigu — Give the book to Natasha

Govoriti za lěs — Govoriti o lěsě — Talking about forest

Znajomec na brat — Znajomec brata — My brother’s friend.

Jesòm v Měnsk — Jesòm v Měnsku — I am in Minsk

Number

How do people understand what is the numeric characteristic of the object? Of course, the simpliest way is to use numerals. We can call to a numeral and link it with some noun, thus, people will understand that there is an amount shown by a numeral of the concept shown by a noun. But it is rather uncomfortable to use near every noun an additional numeral. Mostly due to the fact we seldom know the exact amount of something. That is why there exists a term of number.

Number shows what is the amount of some concept without using numeral before the noun.

Number is a grammar property of the word, its alteration. That means when we change number of the word, we change the word itself and not add some additional words or particles around the word we are speaking about.

There are three numbers in Novoslovnica: singular, dual and plural. Singular and plural are familiar to an English speaker. They show whether the object is single or not. Dual is rather peculiar, so we should take an additional account on it.

A dual number is used when we speak about a pair of something — hands, legs, eyes etc. of one person. Two-doors gates, two boolean values, two antipodes etc. In these cases we use a dual number. Having a pair is a rather frequent fact, so this number appeared in Proto-Indo-European. Dual number so as plural one depends on the word which is spoken so we cannot determine a static rule about choosing a form for a dual number. We can get a dual form of the word by using a declension function with a type of declension corresponding with the word given as a parameter.

Wd = decl (W, Td)

There also exists an additional number form we should speak about that is so-called as a counting form. A counting form is used with the nouns. It only occurs when we use the noun with the numerals «two», «three» or «four» (cardinal numbers). The counting form is equal to a dual number in writing so we can speak of it as an extension of a dual number usage.

Examples:

Dva doma (two houses) — counting form

Doma (two ones) — dual number

Tri doma (three houses) — counting form

Domy (three ones) — plural number

Person

This grammar category determines the person who is spoken about. There are three points of view:

— the point of the speaker (First person)

— the point of the interlocutor (Second person)

— the point of other persons, that are not involved into discussion (Third person)

That is how a Slavic discussion could be seen. Practically, this concept is similar to all European languages, particularly English. There is a total equivalency with English in Novoslovnica, so it is not necessary to describe the usage all of these person types. Just look at the following examples to get sure of it:

Examples:

Ja glědaju v prozorec cěl věčôr. — I am looking outside of the window for the whole evening. (The first person)

Vy kažete že sámo ïsto byše včera? — Do you mean that the very same thing was yesterday? (The second person)

Ony hlåpcy niĝda ne mogut pjiti tïho. — Those guys never can drink quitely. (The third person)

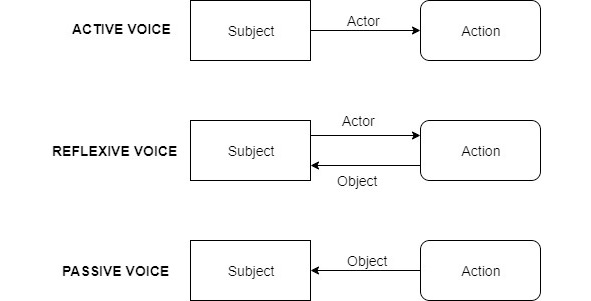

Voice

Voice is the most common feature describing the predicate. It describes the relationship between the action the predicate expresses and the participants of the action (the subject, objects etc.).

There are three voices in Novoslovnica:

— Active

— Reflexive

— Passive

Active voice

The active voice describes a sentence where the subject performs the action stated by the verb.

Examples:

Moǐ brat sę zova Ivan. — My brother’s name is Ivan.

Glědaǐ u prozorec! — Look at the window!

Reflexive voice

The reflexive voice describes a sentence where the subject plays the both the role of the actor and the object.

Examples:

Ja sę učim govoriti anĝliǐskym jazykom. — I learn how to speak English.

On sę glědaje v zòrcadlo. — He is looking at himself in the mirror.

Passive voice

The passive voice describes a sentence where the action stated by the verb is acted over the subject.

Examples:

Ryba je byla zjědena kotom. — The fish was eaten by a cat.

Moǐ prijatelj je byl prijęt do råboty. — My friend was accepted for the job.

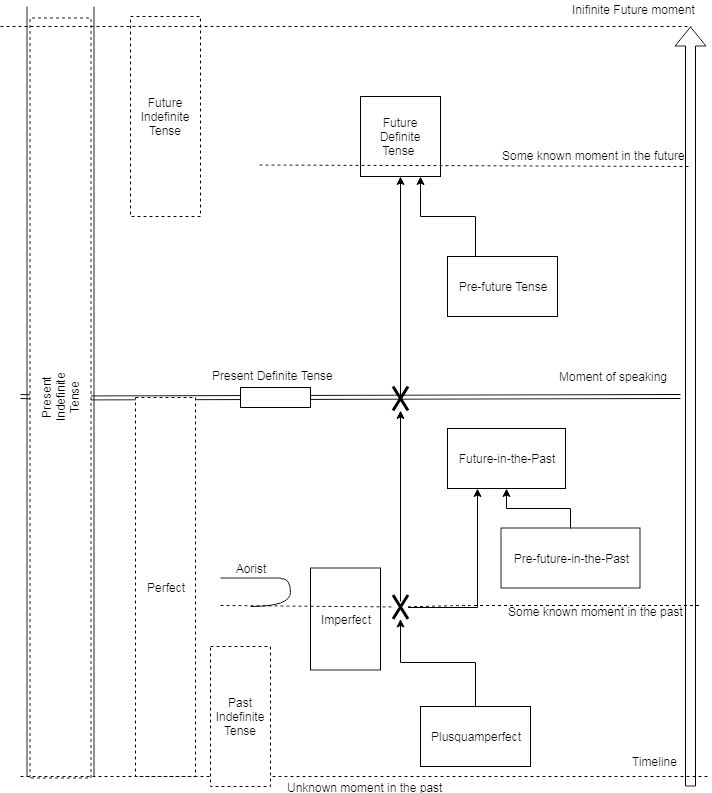

Tense

Grammatical tense is a category that expresses time reference with reference to the moment of speaking. In many languages there are three main categories of present, past and future, that refer to the moment of speaking, the period before and the period after it respectively. English belongs to the group of languages with tense-rich grammar. It has 16 tenses, divided by categories of time and perfection. Novoslovnica has 12 tenses, based on the two principles like English. They are:

— Present Indefinite Tense

— Present Definite Tense

— Future Indefinite Tense

— Future Definite Tense

— Pre-future Tense

— Future-in-the-Past Tense

— Pre-future-in-the-Past Tense

— Aorist

— Perfect

— Imperfect

— Plusquamperfect

— Past Indefinite Tense

First two tenses describe the present moment, the next three ones refer to the future period of time and the last six ones describe the period of time that has already passed.

We can divide past tenses in two groups - past tenses itself and future-in-the-past tenses, that describe actions that refer to the future moment with reference to the moment in the past.

Novoslovnica tense system can be described better with the help of the following diagram:

Present group of tenses consists of Present Indefinite Tense (Pritomen čas) and Present Definite Tense (Sëdyšen čas).

Present Indefinite Tense (Pritomen čas) is used when the action does not depend on time. For example, in the first example we know that the Earth always revolves and nothing but the apocalypsis can change it. This tense is very similar to the English one and has similar use cases. We can find this tense in indicative (examples 1, 2) and declarative (example 3, 4) moods mostly (in some cases it can be found in different moods too).

Note that in declarative there are two variants of present indefinite, because of its resultive semantics. In example 3 you can see the verb in declarative mood, in present indefinite tense, and in example 4 you can see the same tense and mood but within a predicateless sentence.

Also take care of the translation in example 3. You can mess it with English Present Perfect Tense (He has bought two cars), but this sentence should be translated with the verb «to have» in Present Indefinite with the participle III of the verb «to buy» (bought).

Examples:

Zemlä sę vreta okolo slånca. — The Earth revolves around the Sun.

Vsękyǐ denj ja hođam do učilišta prez lěpyǐ park. — Every day I walk to school through the beautiful park.

On imá kupeno dva vozidla. — He has two cars bought.

Lěs i tïhota… — There are forest and silence around me…

Present Definite Tense (Sëdyšen čas) is used if the action depends on time. In the first example we can see a sentense with the following semantics: now I think about the rest, though in an hour I can forget about this thought.

Generally, this tense is close to Present Continuous Tense in English, though has a different interpretation. If you want to get in differences, we can give you such an example: «The Earth is revolving around the Sun at the moment». Read this hypothetic sentence that is syntaxicly valid in English.

What would be the differences of English and Novoslovnica here? It is in a term of differentiation. English operates with the time and Novoslovnica operates with the mutability. That is why here Novoslovnica will still use Present Indefinite Tense with the word «sëdy» (at the moment).

Examples:

Ja myslü o počïvkě. — I am thinking about the rest.

On idaje do råboty, zato ne može da odgovori vam. — He is going to the work, that is why he cannot answer you.

The group of future tenses comprises three ones: Future (Definite) Tense, Pre-future Tense and Future Indefinite Tense.

Future Definite Tense (Bųdešt čas) defines that the action will appear in the future with reference with the moment of speaking. There are three variants of how you can use Future Tense in Novoslovnica.

Firstly, you can use the verb «hteti» (to will) in 3-person form with the main verb in Present Indefinite Tense (example 1). This varitant is most similar to English Future Simple Tense.

Secondly, you can use the verb «byti» (to be) with infinitive form of the main verb (example 2). This variant is close to English Future Continuous Tense. It is often used with verbs of A-type (read the chapter about verbal types in Novoslovnica).

Finally, you can use a synthetic verb form with the future tense conjugation (example 3). In English, it should be translated in Future Simple so as the first one.

Examples:

Ja hte kazam ti něčto. — I will tell you something.

Ja bųdu sluhati gudbu. — I will listen to music. (I will be listening to music).

Nakonec ja tę viđahtem. — Finally, I will meet you.

Pre-future Tense (Predbųdešt čas) is a grammatical tense that is used when the speaker should explicitly show that the action will take place before another future action. So, this tense deals with the comparison of future actions rather than with the moment of speaking.

In Novoslovnica Pre-future Tense is formed by using the verb «hteti» in 3-person form with the main verb in perfect form (examples 1, 2). This tense should be translated in English with Future Perfect Tense.

Examples:

Ja hte sòm kupil květy, dy ty hte priǐdaš do města. — I will have bought flowers, when you come to the place.

On hte je zakončil učilišto, dy otec mu hte sę vreta dodomu. — He will have graduated from school, when his father comes back home.

Future Indefinite Tense (Něĝdašen čas) is a rather rare tense to be used in Novoslovnica. It has no direct equivalents in English and should be translated in Future Simple with some keywords (such as «somewhen», «ever», «once»). The sense of this tense is to show that the action takes place in a future moment or period of time, but we do not care of when it will occur or how long it will last.

This tense is formed by Pre-future form of the verb «byti» with the past passive participle of the main verb. Look at the examples to get acquainted.

Examples:

On hte je byl nagrådil medalom mę. — Once he will grant me with a medal.

Ja hte sòm byl kupil vašu věčj. — Once I will but your item.

All other tenses are related to the past period of time. Firstly, we will consider real past tenses and then future-in-the-past ones.

Aorist (Prost minul čas) determines the fact of the committed action without semantic details. It is similar in usage with English Past Simple Tense. Using Aorist we consider only the time the action occurs, but do not think about its duration.

In Novoslovnica it is formed by verb-base vowels with past definite endings: «-h», «-ša», «-še», «-hma», «-hta», «-ha», «-hme», «-hte», «-hu».

Examples:

Ja dělah råbotu-ta včera. — I did the work yesterday.

Pred dvě ročiny ja jěŝih v gråd-òt. — Two years ago I travelled to the city.

Imperfect (Neporęden minul čas) determines the imperfect aspect of the past action. That means it is used with habitual, durable repeated actions etc, that took place in the past. Using imperfect we add the information, that our action took some exact time in the past. This tense is similar in usage with English Past Continuous Tense or Past Perfect.

It is formed so as Aorist with the one difference. There is a «-ě-» vowel before endings, not the verb-base vowel. So, for any verb type (see a chapter about verbal types) there is only a single imperfect form.

Бесплатный фрагмент закончился.

Купите книгу, чтобы продолжить чтение.