Бесплатный фрагмент - Indo-European ornamental complexes and their analogs in the cultures of Eurasia

The book of outstanding researchers S. V. Zharnikova is devoted to the study of the ancestral home of the Indo-European peoples: Indian, Iranian, Slavic, Baltic, German, Celtic, Romance, Albanian, Armenian and Greek language groups. Part Four of this huge work is devoted to the ornamental complexes of the Indo-Europeans.

Перевод осуществлен Виноградовым А. Г.

Иллюстрации взяты из издания книги “Орнаментальные комплексы индоевропейцев и их аналоги в культурах Евразии” на русском языке.

Translation by A.G. Vinogradov The illustrations are taken from the Russian edition of the book “Орнаментальные комплексы индоевропейцев и их аналоги в культурах Евразии”.

Introduction

In the modern world, the urgency of the problems of the ethnic history of the peoples of various regions of our planet is obvious. The growth of ethnic self-awareness, which has been observed everywhere in recent decades, is accompanied by an increase in interest in the historical past of peoples, in the transformations that each of them experienced in the course of its millennia-old formation. It became a spiritual need for a representative of a modern urbanized society to find the roots of his ethnic existence, to understand the diverse processes that led to the formation of that ethnocultural environment through which he perceives the world around him.

Since the origin and historical existence of the overwhelming majority of the peoples of our planet was associated with numerous migrations, movements to new habitats, causing changes in a number of cultural factors both among the alien people and the indigenous population, today, studying the ethnic history and culture of their people, we, of course, study them in the process of historical transformations and mutual influences of many tribes and peoples, which to one degree or another took part in their formation. Regional ethno-historical research in our time is becoming especially acute, since it is knowledge of the history of one’s own people that helps a modern person to free himself from the narrowness of the nationalist view of the world, to understand the role and significance of the contribution to the common treasury of human culture of all peoples, to realize that humanity is one.

Of course, it is impossible to solve the most difficult issues of ethnic history today without involving data from the most diverse fields of science. It is necessary to combine the efforts of ethnographers, historians, archeologists, linguists, folklorists, anthropologists, art historians, as well as paleobotanists, paleozoologists, paleoclimatologists and geomorphologists, since the development and formation of peoples took place in certain climatic zones, in certain landscapes, with a certain flora and fauna, and this must be taken into account.

Only if the questions posed by ethnic history will be given mutually supportive answers by all of the above branches of science, we can, with a certain amount of confidence, believe that we are close to a true understanding of a particular stage of the historical process. Therefore, at present, the search for an answer to any of the questions of the ethnic history of peoples cannot be considered legitimate without involving data from related sciences.

Part I Geometric ornament of North Russian embroidery and weaving its possible origins and analogues in ancient cultures of Eurasia

1

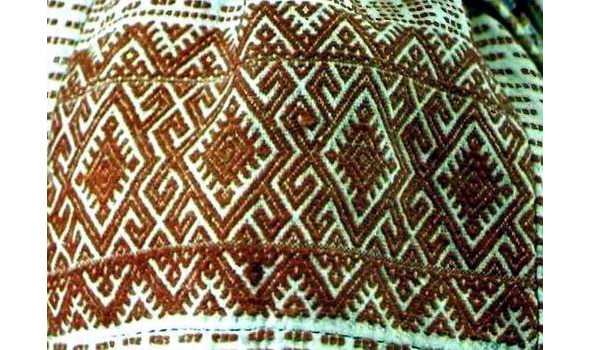

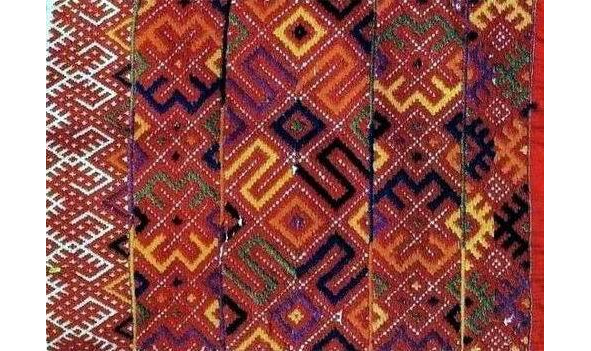

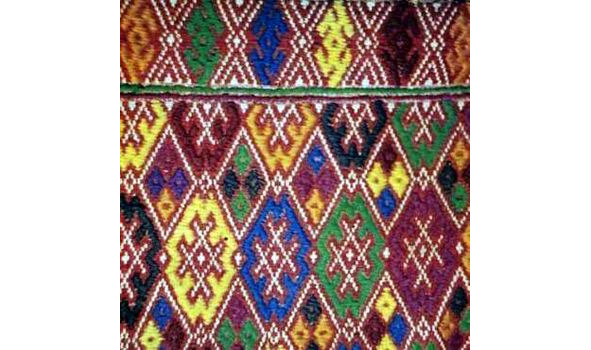

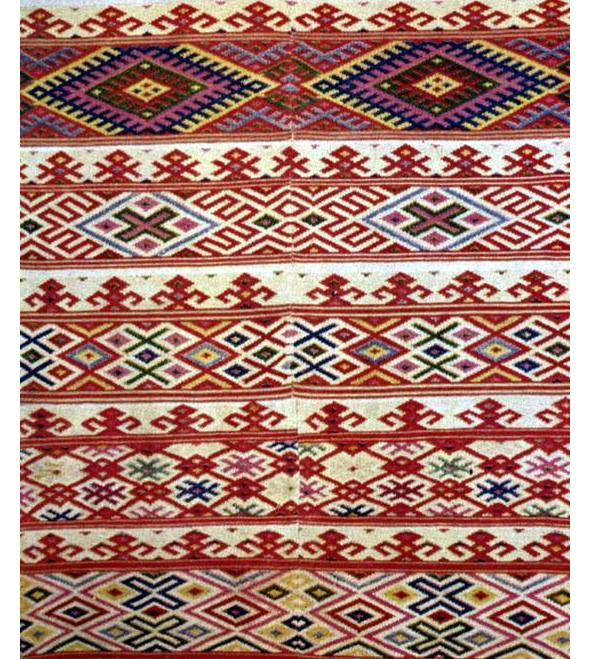

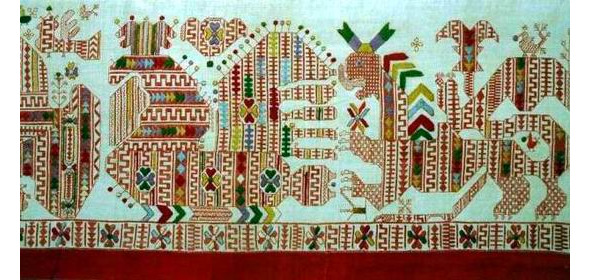

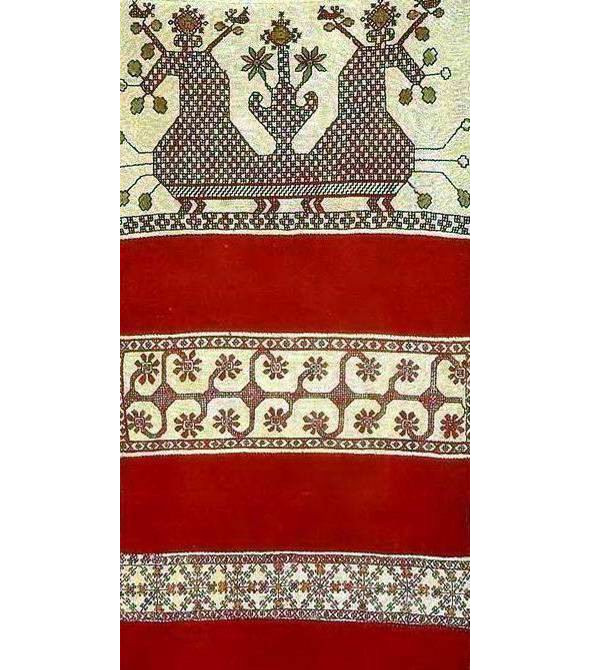

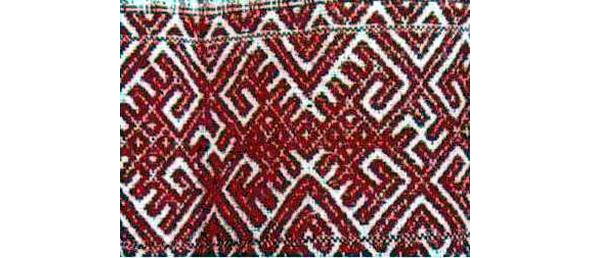

An outstanding researcher of the Russian North A. Zhuravsky wrote in 1911: “In the” childhood “of mankind — the basis for knowledge and direction of the future paths of mankind. In the eras of the” childhood of Russia "- the path to knowledge of Russia, to control knowledge of those historical phenomena of our modernity that it seems to us fatally complex and not subordinate to the ruling will of the people, but the roots, which are simple and elementary, like the initial cell of a complex organism. The embryos of social “evils” are in the personalities of everyone and everyone. the experiences of the grizzled past, and the closer we get to the embryos of this past, the more consciously, more truly and more confidently we will go forward… It is the history of “childhood of mankind”, namely ethnography, that will help us to know the logical laws of natural progress and consciously, and not blindly, go forward and to move our people forward ourselves, for ethnography and history are the ways to know that “past”, without which it is impossible to apply the knowledge of the present to the knowledge of the future. Turning to the millennial depths of the historical memory of the people, we, first of all, will try to reveal, more objectively, those similarities and analogies in the sphere of the spiritual life of the Slavs and Indo-Iranians that go back deep into these millennia. I would like to start the analysis from the works of folk arts and crafts-weaving, embroidery and woodcarving that existed in the Russian North, on the one hand, and similar works of folk art of modern Indo-Iranian peoples, on the other. The connecting thread between these two regions, so remote today, will be that numerous archaeological materials, starting from the Upper Paleolithic period and ending with the developed Middle Ages, from the vast territories of Eurasia, which modern historical science has. The basis for such comparisons is that ethnographic materials, in particular abusive weaving, embroidery, and woodcarving, which existed in the Vologda and Arkhangelsk provinces until the beginning of the 20th century, indicate the preservation, albeit in a relict form, of the memory of ancient Slavic-Indo-Iranian contacts, or rather — kinship. Analogies of ornamental compositions characteristic of the mentioned types of folk applied art can be found, on the one hand, in the extreme south of the Slavic area: in Bulgaria, Yugoslavia, as well as in Western Ukraine and the Dnieper. On the other hand, such ornamental complexes are characteristic of the folk art of Ossetians, mountain Balkarians, Armenians, Tajiks of the Pamirs, Nuristanis of Afghanistan, the peoples of North India and Iran. In addition, as noted earlier, the specific hydronyms, dialectological archaisms present in the Russian North, have numerous analogies in Yugoslavia, Bulgaria, Western Ukraine and the Dnieper, on the one hand, and in Central, South-West and South Asia, on the other.

The Russian North owes such a good preservation of the deeply archaic elements of traditional folk culture to a number of historical reasons. First of all, it should be borne in mind that Christianity came to these parts quite late. So, around 1260, the chronicler of the Spaso-Kamenny Monastery testified that: “you don’t receive the holy baptism, but you don’t open many many unfaithful people to Kubensky.”

It is interesting that even in the second half of the 19th century, in such counties as Ustyuzhsky, Nikolsky, Solvychegodsky, which occupy most of the province, there were one Church in 150—200 populated areas. To a considerable degree, the relics of pre-Christian beliefs, and therefore traditional folk culture, were well preserved due to the fact that here, in the Russian North, there were no sharp ethnic shifts and the associated population changes, practically no wave of conquerors reached here, here there were devastating wars. Most of the Russian North did not know serfdom, and the peasants were personally free, and as a result of this, both the institution of the traditional peasant community and the ancient ritual-ritual practice were preserved for a very long time.

We can assume that the preservation of the elements of folk culture in the Russian North in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, often archaic not only of the ancient Greek, but also recorded in the Vedas, is due to the fact that the population of these places was largely descendants of the ancient population, formed here as a result of advances until the Bronze Age, a time when, perhaps, many social structures, mythological schemes, and those ornamental forms that were common to the vast Slavic-Indo-Iranian region and were preserved in relict form until our days. V. V. Stasov, a well-known researcher of Russian culture, wrote about such relic ornamental forms: “In the ornament of Russian embroidery are precious and as yet untouched materials for studying different sides of ancient Russian nationality.” Indeed, for more than a century, Russian embroidery and abusive weaving have attracted the closest attention of researchers. At the end of the last century, a number of brilliant collections of works of these types of folk art were formed. The studies of V. V. Stasov, S. N. Shakhovskaya, V. Ya. Sidomon-Eristova and N. P. Shabelskaya laid the foundation for the systematization and classification of various types of Russian textile ornaments; they also made the first attempts to read complex “plot” compositions especially characteristic of the folk tradition of the Russian North.

The sharp rise in interest in folk art in the 20th century brought to life a whole series of works devoted to the analysis of subject-symbolic language, technical features, and regional differences in Russian folk embroidery and weaving. However, most of the works focused on anthropomorphic and zoomorphic images, archaic three-part compositions, which include a stylized and transformed image of a female (more often) or male (less often) pre-Christian deity. It is this group of plots that has so far caused the greatest interest among researchers. The geometric motifs of the North Russian branded weaving, as a rule, accompanying the main detailed plot compositions, are somewhat different, although very often in the design of towels, belts, hem, sleeve and mantle shirts it is the geometric motifs that are the main and only than they are extremely important for researchers.

I must say that, along with the consideration of complex plot schemes, serious attention was paid to the geometric layer, as the most archaic in Russian embroidery, in the well-known articles of A. K. Ambrose. In the fundamental monograph by G. S. Maslova, published in 1978, the problem of the development and transformation of geometric ornaments is widely considered from the standpoint of its historical and ethnographic parallels, but, unfortunately, do not go deeper than the beginning of the 1st millennium AD. B. A. Rybakov paid and pays exceptionally great attention to archaic geometrism in Russian ornamental creativity. And in his works of 60—70 and in studies on paganism of the ancient Slavs and Ancient Russia published in 1981 and 1987, the idea of the endless depths of folk memory that preserves and carries through the centuries in images of embroidery, weaving, painting, carving, toys, the oldest worldview patterns, leaving their rooted in the millennia. B. A. Rybakov believes that the origins of many ornamental motifs that survive in Russian art until the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th century should be sought in the depths of the Eneolithic and even Paleolithic, i.e. at the dawn of human civilization. Of exceptional interest in this regard are the collections of museums of the Russian North, i.e. those places where the Slavs lived already in the first centuries of our era, long before the baptism of Russia. Remoteness from state centers, relatively peaceful existence (the Vologda region, especially in its eastern part, practically did not know wars), the abundance of forests and the protection of many settlements by swamps and impassability — all contributed to the preservation and preservation of patriarchal forms of life and economy, careful attitude to the faith of the fathers and grandfathers and, as a consequence of this, the preservation of ancient symbols coded in embroidery and weaving ornaments.

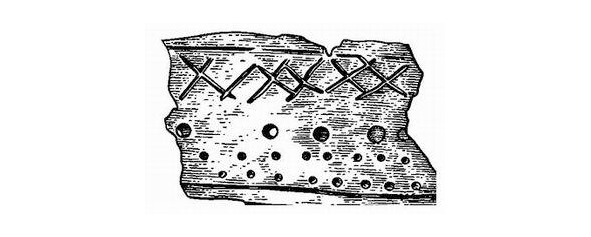

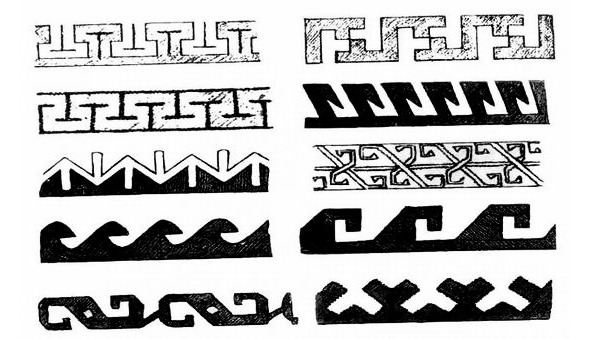

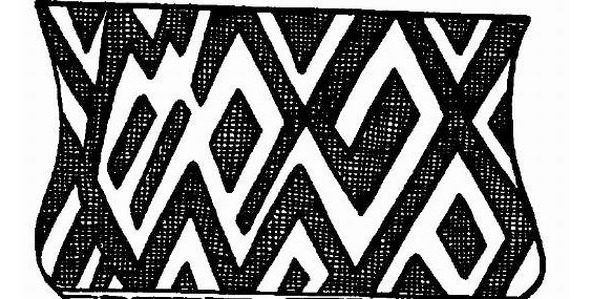

And so, one of the most ancient ornamental motifs of the peoples of Eurasia is a slanting cross, rhombus and meander, appearing for the first time in Eastern Europe (Kostenkovskaya and Mezinskaya cultures) on products from marl, bone and mammoth tusks already during the Upper Paleolithic (26—23 thousand years) ago).

A. A. Formozov notes that already in the Middle Paleolithic (during Mousterian time) there is a big difference between the Mousterian monuments of the Russian Plain and the Caucasus, on the basis of which he considers it possible to talk about the formation of ethnocultural areas on the territory of the European part of the USSR in the Stone Age.

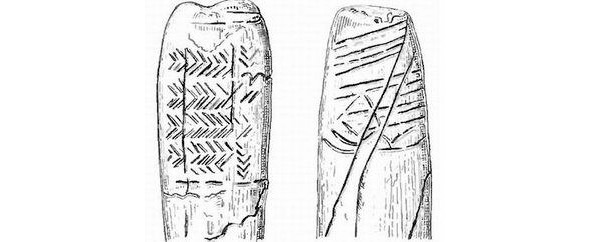

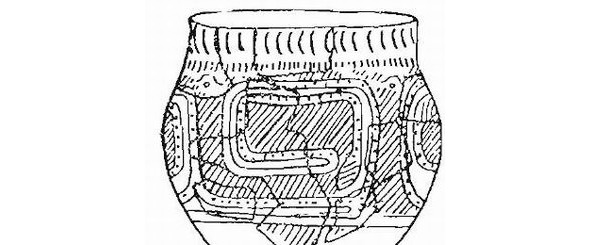

In the Upper Paleolithic, the difference between the southwestern historical and cultural region and the neighboring areas of the Dnieper and Northern Black Sea regions is also noted, despite the fact that researchers emphasize the vast expanses from the upper reaches of the Dnieper basin, the entire Volga basin to the Ural Mountains, which have been studied poorly and, therefore, do conclusions here are not yet possible. One of the most important ethnocultural differentiators, along with the characteristic features of the flint and bone industry, the house-building system, zoo and anthropomorphic sculpture, even at that time, was ornament. So in the II cultural layer Kostenok 14 near Voronezh (abs. Age 26—28 thousand years ago) and in Vladimir Sungir (abs. Age 24—25 thousand years ago), dating from the early Upper Paleolithic, were found made in a certain stylized ornamented bone products and mammoth tusk. Researchers note: “their carved geometric and dimpled ornaments are preserved and developed in the subsequent heyday of the Late Paleolithic cultures of the Russian Plain.” Analyzing the ornaments of the last stages of the Kostenkov culture M. D. Gvozdover comes to the conclusion that: “the oblique cross is most often found from the elements of the ornament… Obviously, this ornament should be considered the most characteristic for the Kostenkov culture, especially since in other Paleolithic cultures the ranks from oblique crosses are almost unknown. “She further notes that the choice of ornament and its location on the subject is not due to technological reasons or material, since the same ornament was applied to a flat and convex surface, to a tusk, bone or marl, but to cultural tradition. Thus, already at this early stage in the history of human civilization, “the archaeological culture is characterized by both the elements of the ornament itself and the type of arrangement on the ornamental field and the grouping of elements.” The rows of oblique crosses that first appeared on the products of the Kostenkov culture did not disappear along with the cultural tradition that gave rise to them. We can trace these signs on the monuments of different, successive, archaeological cultures of Eurasia. They are found on Neolithic ceramics, on the products of Trypillian potters, on the vessels of the Afanasyevsky, Yamnaya, Srubnaya, and Kushetin-Komarov cultures.

As they obstructed the oblique cross on the bottoms of clay Slavic plates, they marked the sculptures indicating the path to the top of the sacred Sobutka Mountain near Wroclaw in Silesia, created no later than 5th century AD, they were placed on the ceramics of Kievan Rus, and until the end 19 century the North Russian peasants decorated the ends of the spinner’s claws with these rows of oblique crosses.

It is difficult to find in the Russian North an instrument of peasant labor made of wood — whether it be a spinning wheel, sewing machine, flax, a wooden stand for a sunflower, on which a slanting cross or a number of such crosses as a single ornamental motif would not be cut or scratched anywhere oblique crosses are quite often found on the woven spacers of the North Russian peasant women.

All this testifies to the fact that ornamental complexes and signs that have developed even in the depths of the Paleolithic survive almost unchanged almost to the present day, and, passing through millennia, they do not lose their main meaning — a sacred sign, because what else can explain the cutting of an oblique cross under the bottom of the spinning wheel, on the handle flax, the cutting of a number of oblique crosses on the lapaska’s torn where no one sees them in general, or the presence of only oblique crosses on a branded spacer sewn to a holiday towel or hem smart women’s shirt.

3

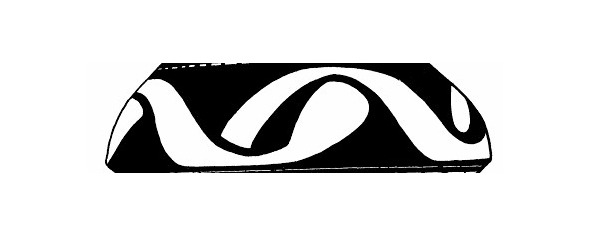

The next group of the oldest ornamental motifs on the territory of the European part of our country is represented by a rhombus and rhombic meander, first appearing on products from mammoth tusks originating from the Mezinsky Late Paleolithic site in the Chernihiv region. As noted earlier, paleontologist V.

Bibikova in 1965 suggested that the meander spiral, torn meander stripes and rhombic meanders on objects from Mezin arose as a repetition of the natural pattern of mammoth tusks of dentin. From this, she concluded that a similar ornament for the people of the Upper Paleolithic was a kind of magical symbol of the mammoth, embodying (as the main object of hunting) their ideas about wealth, power and abundance.

It is the Mezin ornament, which has no direct analogies in the Paleolithic art of Europe, which can be placed “on a par with the perfect geometric ornament of later historical eras, for example, the Neolithic and copper-bronze, in particular, the Tisza and Tripoli cultures.”

Once again, I would like to emphasize that, comparing the Mezinsky ornament with North Russian weaving, V. A. Gorodtsov exclaimed in 1926: “reminiscence (a vivid memory) of the most ancient universal human religious secrets is hidden in the patterns of North Russian skilled craftswomen symbols. And how fresh, what a solid memory!”

The Mesolithic period that followed the Paleolithic remains, until today, a white spot in the history of ornamentation. At this time, the researchers note, there was a widespread transition of the population of Eastern Europe from settledness to a mobile, wandering existence, which is probably due to the disappearance of the mammoth, which was the main object of hunting. Thus, products from tusks and mammoth bones were no longer produced, while ceramics appeared only in the Neolithic. But we have no reason to believe that the Paleolithic ornamental motifs, in particular the meander ornament of the Mezinsky site, disappeared forever. Probably, in the Mesolithic ornamental tradition continued to exist and develop on products made of such materials as leather, birch bark, wood, plant fibers. This is evidenced, for example, by patterns on wooden products of the Mesolithic age (7—6 thousand BC) found in the 1st Visa peatland near Lake Sindor in the Komi Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic. These patterns of zigzags, parallel lines and oblique mesh are repeated without changes then on the Neolithic Kargopol ceramics.

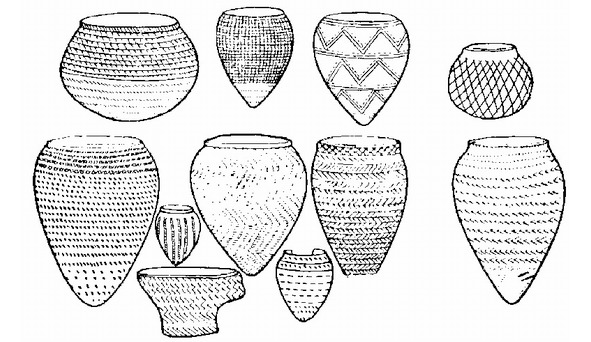

Only the preservation of the ancient Paleolithic ornamental traditions in the Mesolithic can explain the fact that the Neolithic ceramics of the vast region from the Dnieper to the Balkans and the Northern Caspian Sea have the same meander patterns and their various modifications as on the Mezin bone products (Table 1).

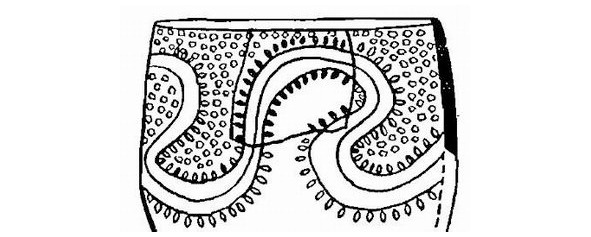

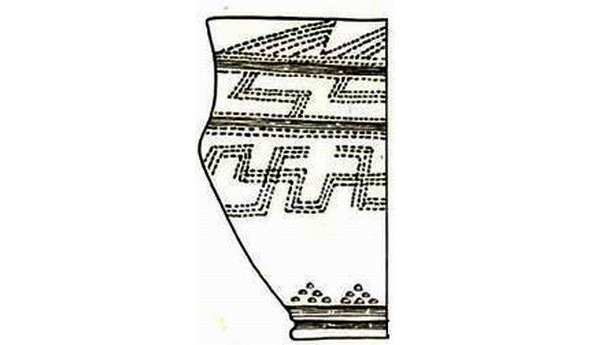

At the many Neolithic sites of Ukraine, one of the most common at that time was a positive-negative meander ornament: fragments of ceramics from the Mitkov and Bazkov islands, from the settlements of Gayvoron-Polizhok, Vladimirovka are decorated, as a rule, with a complex meander pattern (Table 2.3). Published these materials V. N. Danilenko noted that such ornamentation is only partially modified, without disappearing for millennia. He writes: “There is no doubt that such an ornament is preceded by a spiral meander ornament of the later stages of the development of the agricultural Neolithic. At the same time, it is obvious that precisely such ornamental compositions, despite their exceptional antiquity, are already close to Early Tripoli. The last circumstance has to be explained not so much chronological how much ethnocultural proximity of the local early Neolithic with Tripoli.”

B. A. Rybakov, investigating the development paths of the ancient rhombo-meander ornament in the Neolithic, concludes that: “The stability of this complex and difficult-to-implement pattern, its undoubted connection with the ritual sphere makes us treat it especially carefully… Neoenolithic meander and rhombic the pattern turned out to be a middle link between the Paleolithic, where it first appeared, and modern ethnography, which gives innumerable examples of such a pattern in fabrics, embroidery and weaving”. Speaking about the dentin pattern of mammoth tusks, as a possible prototype of the Paleolithic meander-carpet pattern of the Mezin type, B. A. Rybakov notes that: “The amazing durability of exactly the same pattern in the Neolithic, when there were no mammoths anymore, does not allow us to consider this a mere chance coincidence, but forces us to look for intermediary links. I consider the custom of ritual tattooing to be such a mediating link”.

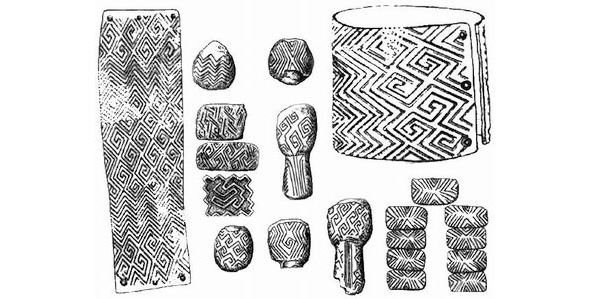

Comparing the Paleolithic bone objects decorated with this ornament with the Neolithic “seals”, he concludes that such stamps were made to tattoo a woman’s body during ritual acts, and that it is the custom of tattooing that is the connecting link that fills the Mesolithic gap between the Paleolithic and the Neolithic. But along with the preservation of the ancient ornament in the form of mandatory ritual coloring in the Mesolithic, it can also be assumed that in the Neolithic period the seals were no longer used for tattooing or not only for it, but at some stage they began to apply carpet-meander patterns on fabrics made of plant fibers, which probably already existed in the Neolithic life, as evidenced by the finds of spinning wheels.

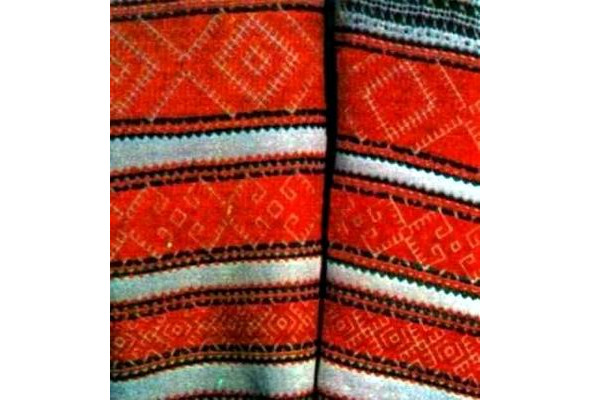

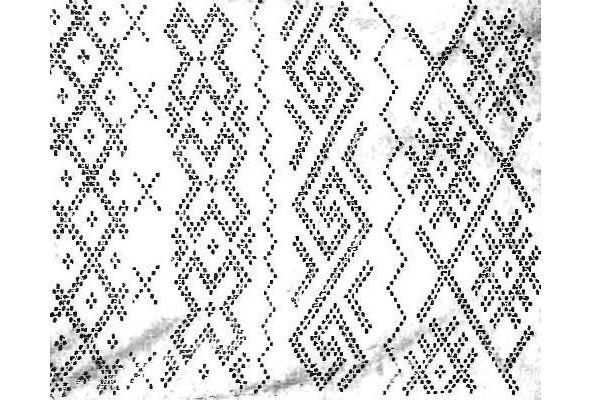

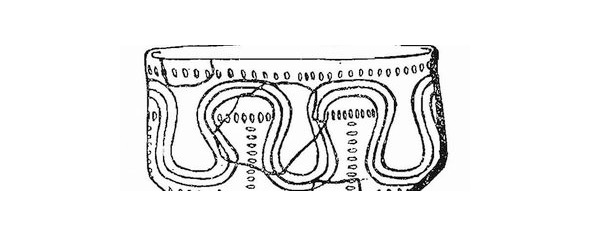

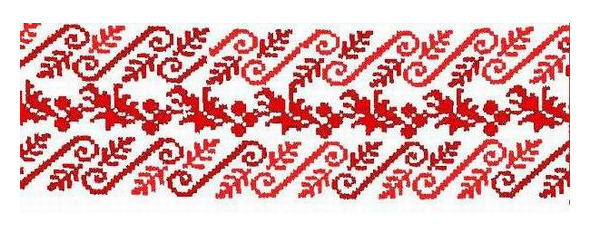

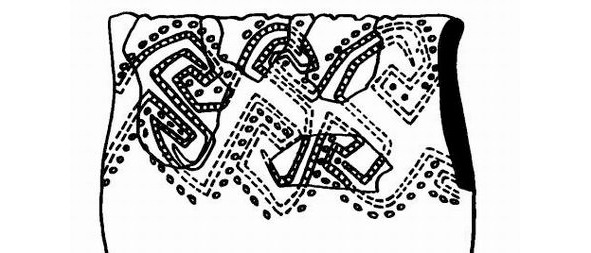

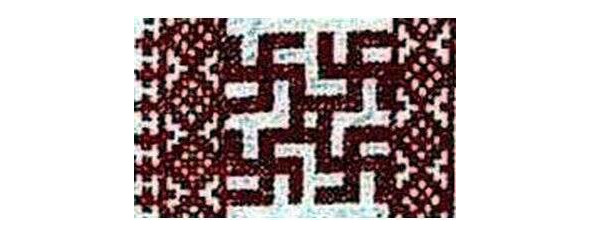

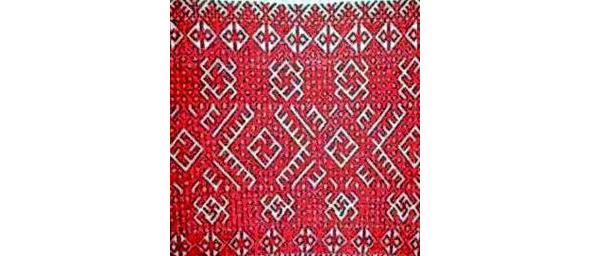

With the development of weaving techniques, the ancient craftswomen of the Neolithic or Eneolithic were able to transfer complex ornaments from rhombuses and meanders directly into the structure of the fabric. Such an ancient carpet-type ornament, almost identical to the Mezin and Early Neolithic, can be easily found on linen canvases that existed in North Russian villages at the beginning of the 20th century. Made in a multi-thread technique, they are all completely covered with a rhombo-meander pattern, obtained with a complex interweaving of warp and weft threads. As a rule, towels, tablecloths, skirts were made of such canvas, to which strips of spacers were sewn, recruited with red threads along a white field. The ornament of these spacers is often very similar to the ancient rhombo-meander, but while the texture of the white canvas repeats the ancient compositions with practically no changes, on the spacers we see, as it were, fragments of an archaic scheme, its parts divided and grouped according to some new principles.

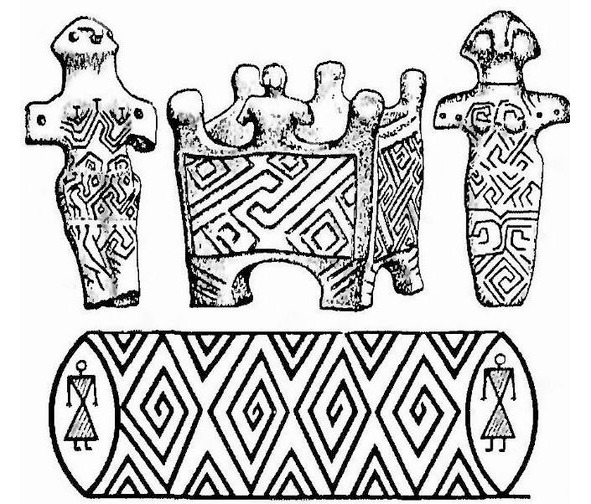

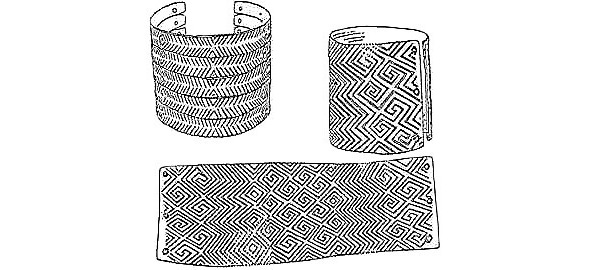

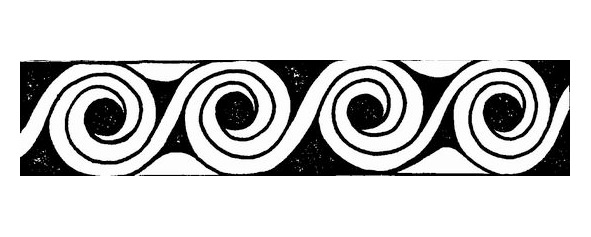

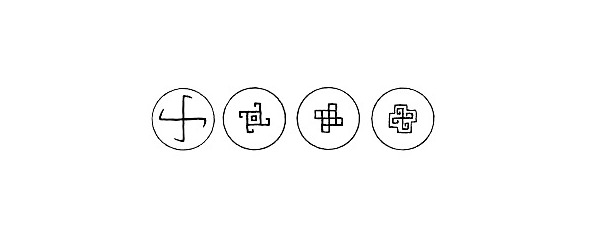

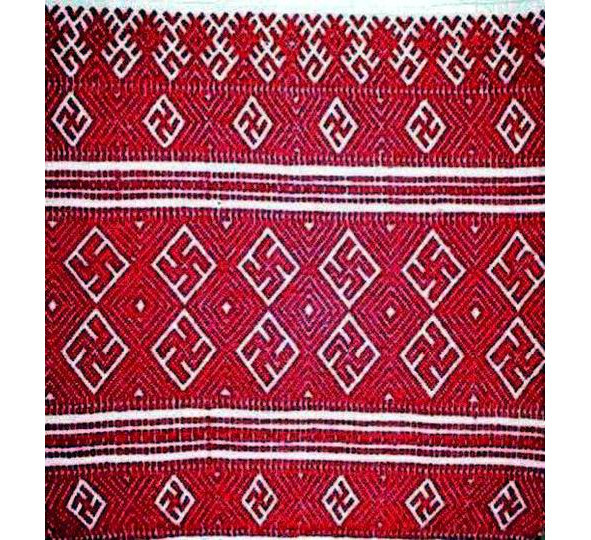

It must be said that the possibility of such variability was laid in the Mezinian ornaments. Despite the outward similarity, the ornaments of items from the Mezin site have a number of differences. So on the bracelet there is a carpet-meander pattern, but on the figurines from the mammoth tusk the pattern is already somewhat different: it is a meander spiral placed among zigzags, parallel meander stripes and a meander, depicted in motion from right to left and left to right, in which the outlines are already quite clearly read one of the most widespread signs during the Eneolithic and copper-bronze on the territory of Eastern Europe — the swastika (Table 4).

This ornamental differentiation becomes even more evident in the Neolithic. So a large number of different variants of ornaments based on the rhombo-meander Paleolithic composition give us Neolithic “seals” (on which one can find rows of S-shaped meander elements — “jibs”, and meander stripes, and swastika elements) and Neolithic clay statuettes depicting women, covered with all sorts of meander composition motifs. B. A. Rybakov notes that if the meander pattern was widely used in the Neolithic for ornamentation of ceramics in general, then “for ritual dishes and plastics, it was almost mandatory”.

There is an opinion in science that the geometric ornament was transferred to ceramics made of soft materials.

Agreeing with this, we can assume that, probably, the same ornaments were obligatory for clothing, at least for clothing that performs ritual and protective functions. We can assume that already on the border of the Neolithic and Eneolithic, marked by an even more vivid flourishing of geometric ornament in Eastern and Southeastern Europe, clothes were decorated with woven ornaments.

This is all the more likely, since “the second half of the 3rd thousand BC refers to the mass distribution of spinning, i.e. the intensive development of spinning, noted not only for Eastern Europe, especially for the Tripolye circle, but also for Asia Minor”. Naturally, we can only roughly imagine what the fabrics from which the clothes of the Eneolithic people were made, but as for the rhombo-meander pattern in its various modifications, its development and transformations at this time are very well illustrated by the ceramic products of the brightest culture of the Eastern Eneolithic and South-Eastern Europe — Tripoli-Cucuteni. B. A. Rybakov notes that in this culture: “The rhombo-meander ornament is found on dishes (especially on ritual, lavishly decorated vessels), on clay anthropomorphic figurines, too, undoubtedly ritual, on the clay thrones of goddesses and priestesses.” V. N. Danilenko, speaking of the fact that even in the early Neolithic in the territories later occupied by the Tripolye culture, meander compositions almost completely dominated, comes to the conclusion about the substrate nature of the meander ornament of the Tripillya dishes and its deep archaism, which numerous positive-negative compositions.

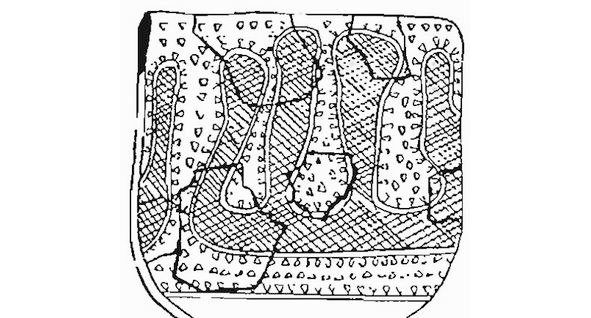

On the ceramics and cult sculpture of the Eneolithic, we find a steadily repeating scheme of the meander pattern, which already somewhat differs from the Upper Paleolithic Mezinian and Neolithic in its great geometrism and clarity of rhythm. This is evidenced by the decoration of ceramic products found in Moldavia in the settlements of Frumushika I, Hebeshesti, Gura Vey. The meander pattern adorns the sides of the Kernosovsky idol found in the Dnieper region: the central phallic image is, as it were, supplemented by side compositions, one of which is represented by a set of zigzag and meander stripes, on the other such zigzag and meander stripes rise above the fertilization scene and the image of a bull with moon-shaped horns under this scene. The whole complex of plots leaves no doubt about their sacred character. A. A. Formozov writes: “Sometimes ancient things have a magnificent pattern covered with areas hidden from the viewer’s eyes — the bottoms of vessels or the reverse side of the plaques sewn onto clothes. From an aesthetic point of view, this is meaningless”. A lot of such senseless from the point of view of aesthetics, but probably playing a huge ritual role of ornaments, we meet precisely on the bottoms of Tripolye vessels.

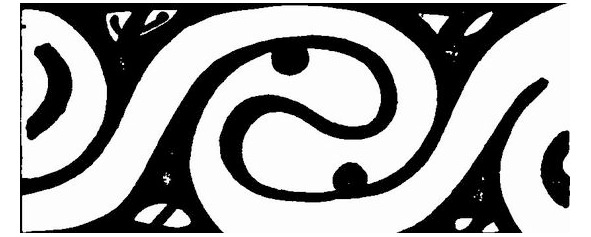

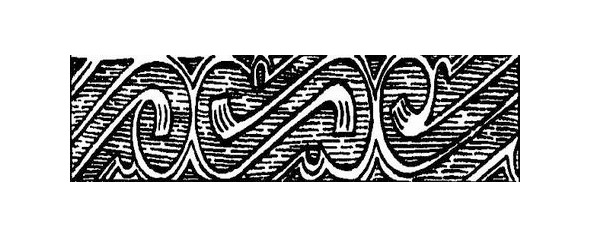

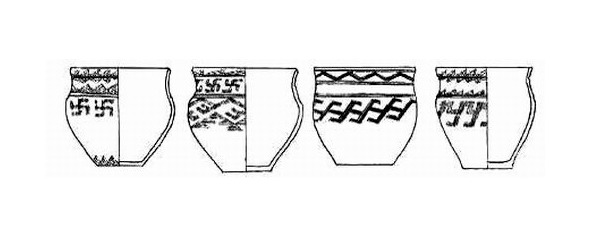

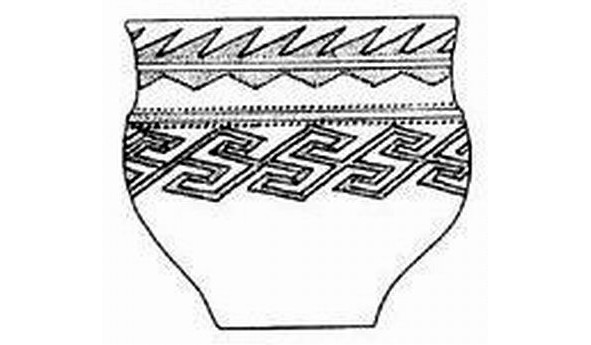

Among these sacred signs, first of all, it is worth mentioning the meander spiral, the swastika used in its simplest version or complicated by new composite elements in the form of additional processes on each curved side of the cross, and the peculiar transformation of the meander motif, represented by the S-characteristic ceramic decor next to S- shaped “geese” (tab. 5). It must be said that throughout the history of Tripoli culture, in any case, at its early and middle stages, two main directions in the development of ceramic ornament can be distinguished.

On the one hand, this is a geometric angular style, using various variations of the meander pattern and most clearly developing the archaic rhombus-meander ornament. On the other hand, this is a drawing of smooth, wilted forms, gravitating to a circle.

V. N. Danilenko writes that: “By the time of the spread of the most ancient painted utensils, the beginning of the bifurcation of the development paths of the Trypillian culture was an obvious fact,” but it manifested itself most vividly when in the eastern half of the Trypillian area — on the Middle Dnieper region, in the Bug region and partly in the Middle Dniester region in the ethno-historical process “a powerful eastern component was included — the early links of the ancient pit culture”. It was here that by the time of the beginning of the transformation (in the process of mutual influences) of both the Trypillian and Yamnaya cultures, which served as the basis for many cultures of the Bronze Age, that circle of ornamental motifs was formed, rather limited and not exhaustive, no doubt, of the entire richness of the Tripillian ceramics decor, but nevertheless less characteristic of this culture, with which materials of subsequent historical periods are to be compared in the future. This is a meander and its varieties: meander spiral, intricately drawn cross-swastika, S-shaped figures — “jibs”.

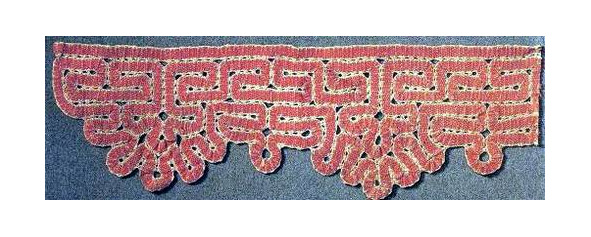

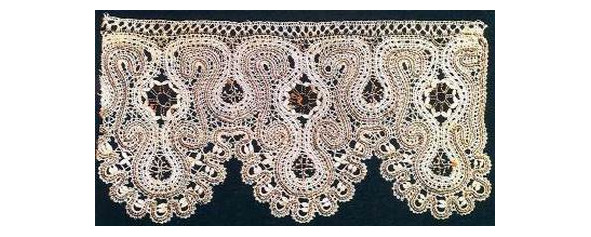

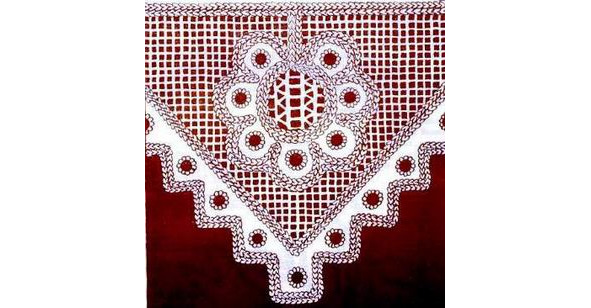

Before we turn to the materials of those cultures that replaced Trypillian and Yamnaya in the Bronze Age, i.e. to the Corded Ware cultures that emerged on the basis of the cultures of Corded Ware: Tshinetsko-Komarovskaya and Abashevskaya, Srubnaya and Andronovskaya, I would like to note that, paradoxically, many ornamental motifs characteristic of Tripillya and disappearing in subsequent genetically related Trypillian cultures survived until the 20th century no changes in the products of the North Russian peasant women. In this respect, the Vologda lace of the 19th century, or rather its peasant version, not designed for urban consumers, is of exceptional interest. In this form of folk art, a geometric layer coexisted at the same time — rhombuses, jibs, swastikas, meanders, and smooth, rounded meander combinations, almost absolutely identical to those of Tripoli.

The basis of the ornament in such lace, which is performed to decorate the ends of towels and valances of wedding sheets, is a dense, up to 1 centimeter wide, ribbon, very often saturated red, which, whimsically wriggling, builds a pattern, and, above all, a meander pattern. It is interesting that such a decorative solution is typical only for North Russian, and in particular, for Vologda lace (Table 3).

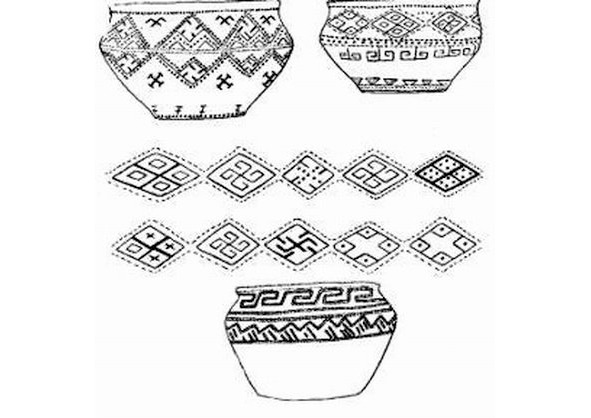

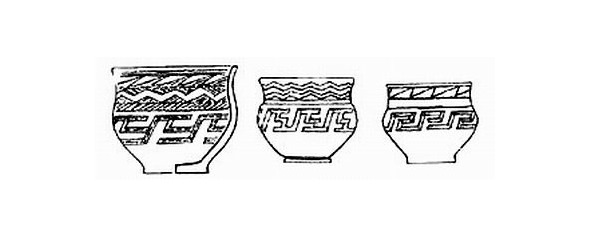

Returning to the monuments of the Bronze Age on the territory of Eastern Europe, I must say that in Trzyniecko-Komarovska; In the ornamental complex, many elements of Tripillya ornamentation are widespread. Thus, on a cult vessel from the village of Pereshchepino, various rhombuses, a meander stripe, a swastika are presented; on ceramics with drawings and signs from Bondarikha there are all kinds of swastika elements, and on items from Vladimirovka rhombuses, swastikas of various shapes, oblique crosses and “jibs” are constantly repeated (Table 6).

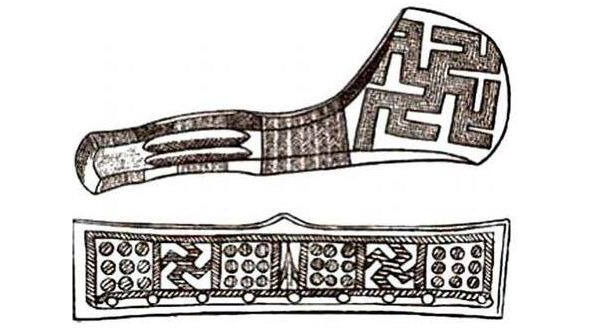

S. S. Berezanskaya connects this ornamentation with the ritual, ceremonial side of the life of people of the Bronze Age. She writes: “It is possible that signs placed on them outside the ornamental system (crosses, rosettes, circles, shaded triangles and rhombuses), which were used as various magic symbols, testify to the cult purpose of some vessels”. The researcher notes that on many vessels of the Srubna culture there are signs that are similar in appearance to runes, which have analogues on the obviously cult objects-spinning wheels, “horned spindle wheels” and miniature “vessels” of the Trzhinets, Belogrudov, Milograd and Bondarikha Proto-Slavic cultures. A. A. Formozov connects these signs, among which there are often oblique crosses, swastikas of various configurations, jibs, with the addition of the peoples of these cultures of writing, which arose on a local basis by schematizing the elements of ornament.

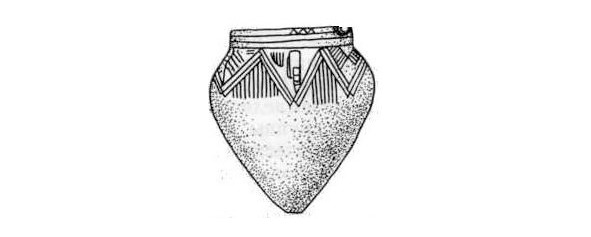

Not all researchers agree with such conclusions, but one thing is indisputable; from what we have today, we can nevertheless conclude that in the Slavic Trinecko-Komarov culture the same signs as in Tripoli — meander, rhombus, swastika, jibs — perform the same sacred functions of the sign — amulet or magic spell addressed to gods and spirits. Turning further to the ornamental complexes of the Abashev culture, we can note that here, as in the Tszynets-Komarska culture, and even to an even greater extent, the ornament consists of various meanders, swastikas and jibs. In contrast to the Abashevskaya, in the ornamental complexes of the Srubna culture, the motif of the meander and the intricately drawn cross is rather rare. The main component of the decoration of the Srubna culture ceramics (16—12 centuries BC according to B. Ch. Grakov) are chains of rhombuses, rhombic meshes and rows of triangles on the shoulders of vessels; the body is often decorated with characteristic oblique crosses, sometimes composed of two overlapping S-shaped forms.

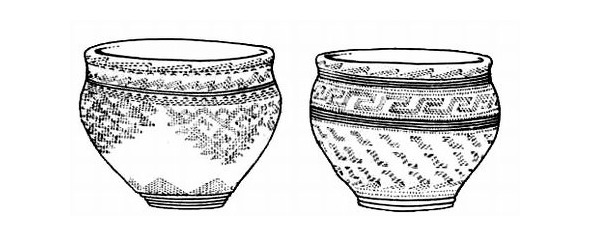

The development of ceramics ornamentation, which includes an amazing variety of different variants of meander and spastic motifs, we see among the closest neighbors of the “Srubniks” — the population of the Andronovo cultural community (17—9 century BC according to E. Ye. Kuzmina). Synchronous in time, these two cultures, as noted earlier, coexisted for a long period in very vast territories of the steppe and forest-steppe zones of our country, spreading in the north up to the Komi-Permyatskiy A.O. (middle course of the Kama River) in its Andronovo-Alakul variant.

In the south, the monuments of the Andronov community go to the deserts and semi-deserts of Central Asia and the highlands of the Tien Shan and Pamirs to the oases of Central South Asia and Afghanistan.

Pottery exhibiting the Andronovo influence was found during excavations in Iran (Tables 2, 3). In the east, the Andronovo culture reaches the Yenisei, and in the north-west, on the territory of Northern Sweden, in the 10—8th century BC. the ceramics of the Andronovo type with a characteristic meander pattern was widespread, which M. Stenberger associates with the Ural-Siberian cultural group. (It is interesting to note that this culture in Scandinavia is replaced by ceramics of the Ananyin appearance, which existed here from the 4th to the 2nd century BC, while the Ananyin culture in the Volga region develops from the 7th to the 2nd century BC). Noting the kinship of ceramic decor among the Timber and Andronovo tribes, S. Z. Kiselev wrote: “…One cannot fail to note the obvious superiority of even the early Andronovo ceramics over its related Timber.” It is impossible to disagree with this; the forms of the Andronovo decor are so rich and varied. The richly ornamented Andronovo crockery in its classic version is known mainly from burial grounds. In connection with this circumstance, M. F. Kosarev makes the following assumption: “Ornate dishes of the classical Andronovo style with rich geometric ornamentation are ritualistic and therefore were especially characteristic in burial grounds and sacrificial sites”. G. B. Zdanovich also believes that the magnificently ornamented dishes were ceremonial, cult. Speaking about ceramics typical for burials, he states that we have before us “a vivid manifestation of cultural traditionalism in the funeral rite”, while in everyday life new dishes have been used for a long time, dishes of old traditional forms are put in burials. “The latter is no longer used for everyday household and household needs, and the very fact of its existence is determined by ritual purposes”. But on the classical (ritual) Andronov dishes, we find the same set of ornamental motifs characteristic of ritual sculpture and vessels in Tripillya — meander, meander spiral, swastika, a number of jibs, etc. While retaining the archetype, they acquire a great variety. Speaking about the specificity of the ornamentation of this ceramics, S. V. Kiselev noted its deep originality, the zonality of the arrangement of various patterns, in which the place of one or another pattern in the zones is usually the same. He said that the complex forms of the Andronovo patterns “were quite likely to be realized with their conditional symbolism… their special meaning, symbolic meaning are emphasized by their special complexity”. M. D. Khlobystina expressed herself even more definitely: “There was, apparently, a kind of communal core, a collective bound by the norms of patriarchal disposition, which, in turn, had certain pictorial symbols of its tribal affiliation, encrypted for the researcher in a complex interweaving of geometric It can be assumed that a kind of leading element of such ornaments is a number of figures located on the shoulders of the vessel: study of the number and combination of these particular patterns, represented by S-shaped signs, meanders, segments of broken lines and their variations, maybe obviously play a role in clarifying the structure of each community.”

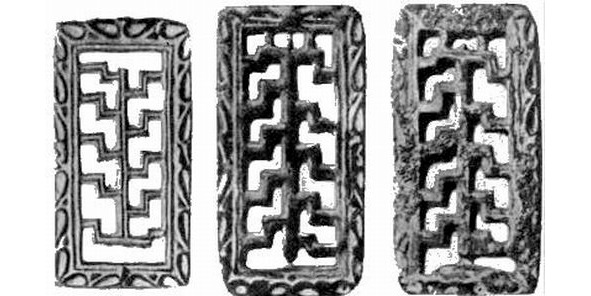

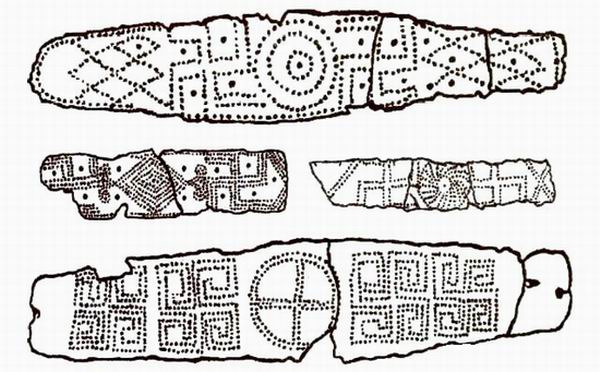

We share the point of view of those researchers who are convinced of the deeply significant content of the Andronovo ornament, consecrated by tradition: after all, it is no coincidence that vessels with just such a decor were placed in the graves, i.e. they probably really performed the functions of a clan or tribal sign, were a kind of “visiting card” in the journey of the deceased to their ancestors, who, by these ornamental “letters”, should have recognized a member of their clan, their tribe. In this sense, the ornament on Andronovo ceramics served as a talisman, protecting its owner on the way to another world or asking the gods for mercy. Thus, we can once again state that the carpet ornament of the Andronov crockery was probably a kind of sign, a symbol of the tribal and ethnic identity of a person whose things were decorated with this particular ornament. In this sense, it, apparently, was preserved in the Karasuk era (12—7 century BC), when the

“Scythian-Siberian animal style” was born, and in the Tagar time (7—1 century BC) BC), since along with the images of animals on the famous Minusinsk openwork belt plates, there is often an ornament typical for the decor of Andronov ceramics, in particular, a lattice of S-shaped elements. Common in the Middle Yenisei in the 3rd — 1st century BC, these plates are found on the territory of Ordos and Inner Mongolia, which was apparently associated with the migration of the population of the southern outskirts of the Western Siberian taiga and more southern and eastern ones that began at the turn of the Bronze and Iron Ages. Areas.

Thus, we can state that the traditional ornament, consisting of meander, swastika and S-shaped forms, characteristic of the decor of Andronov ceramics, existed on the territory of Western Siberia, in particular the Minusinsk Basin, up to the first centuries of our era. Some of these ornamental motifs reach Ordos and Inner Mongolia. In a relict, fragmentary form, many Andronovo compositions continued to live in the art of the peoples of Siberia up to the present day.

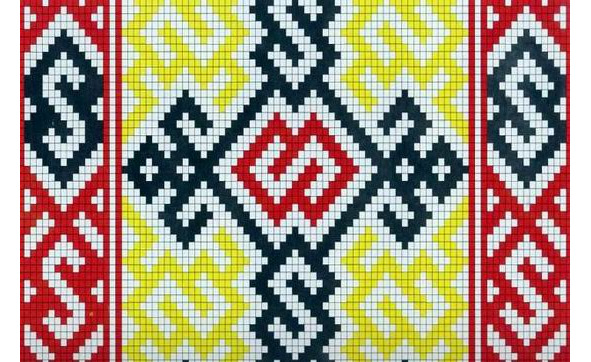

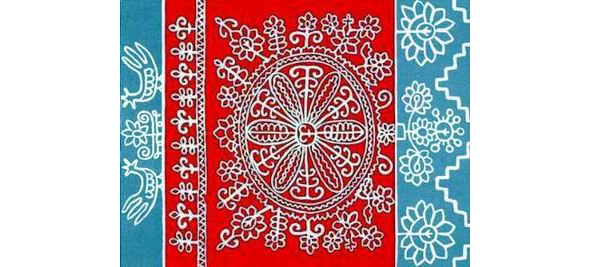

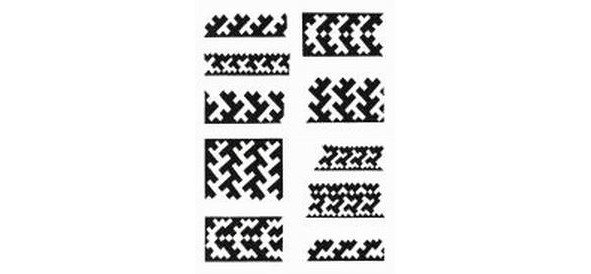

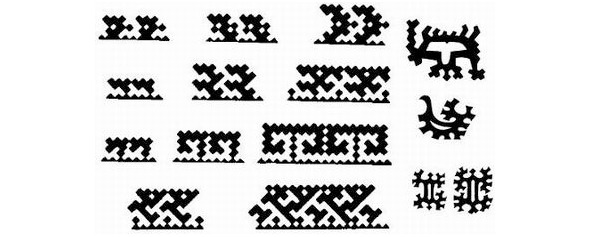

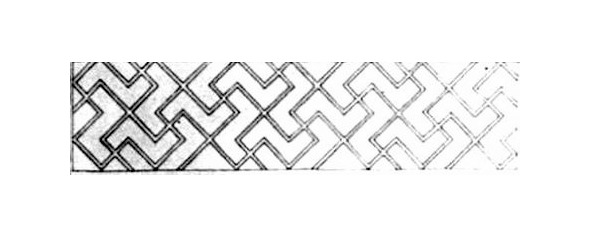

Returning to the European part of our country, in this particular case to the North Russian lands, we must say that, contrary to the prevailing belief in science so far, that the North Russian region is characterized, first of all, by plot compositions, both in embroidery and Even before the 20—30s of the 20th century, geometrically, ornament played a huge role in textile decoration. Moreover, on the branched spacers made by the hands of North Russian peasants in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, not individual elements of the Andronovo ornament, not its later transformations, were preserved, but whole ornamental complexes of the classic carpet pattern, the ritual nature of which was mentioned above. Such ornaments, designed in most cases in the ancient red-and-white color scheme, consisting of meanders, triangles, zigzags, rhombuses, swastikas, “jibs”, decorate the sleeves, hem and shoulder of women’s shirts, the edges of aprons, belts, ends of towels, etc. e. ritual, sacredly marked things that, in addition to purely everyday things, also performed magical and protective functions. As in the entire Andronovo ornament, in North Russian brane weaving, the composition is divided into three horizontal zones, with the upper and lower ones often duplicating each other, and the middle one, as a rule, bears the most important patterns from the point of view of Samantically significant. It is here that you can find the most diverse motifs of meander, “jibs”, swastikas, absolutely identical to Andronov’s, and their convergence is striking.

Turning again to the idea of S. V. Ivanov about the uniqueness of ornamental complexes, that “the tribes or groups of tribes that developed them retain the motives included in the complex for a long time,“and even losing connection with each other, continue to keep communities of these groups”, in our case, we can conclude that the ornamentation of the Andronov ceramics of the 17—11th century BC is likely to be related. and decor of North Russian branded weaving, embroidery and lace of the late 19th — early 20th century. To answer the question of how the tradition could have been preserved for at least 3500 years with practically no changes, it is necessary to find out which ethnic groups were carriers of this tradition throughout this time. Since in science there is a widespread opinion that there were rather long and ancient ties between the Indo-Iranian and Finno-Ugric areas, and, in addition, the north of the European part of the USSR, as a rule, is considered as the territory inhabited by the time the Slavs arrived here in the 1st millennium AD. By the Finno-Ugric groups, it is natural to assume that the bearers of the Andronov ornamental tradition were precisely the Finno-Ugrians, who adopted it in ancient times from the Indo-Iranians and preserved it until the end of the 1st millennium AD. It is assumed that most of this Finno-Ugric massif was assimilated by the Slavs, but, nevertheless, peoples such as Karelians, Vepsians and Komi continue to live among the Russian population, not dissolving in it, preserving the language and ethnic traditions.

Ornament is not the last among these traditions. Thus, if the Andronovo ornamental complexes were preserved precisely by the Finno-Ugric population of the north of the European part of the USSR, then these complexes must be constantly present, and in their ancient forms — archetypes, in the weaving and embroidery of these peoples. However, analyzing the patterns of their textiles, we find only a few motifs typical for the decor of Andronov ceramics. Moreover, as G. N. Klimova notes: “in the textiles of the Komi peoples, later features are most widely represented”. In addition, she points to the fact that the development of the art of typesetting weaving in the late 19th and early 20th centuries was characteristic of the western groups of the Komi-Zyryans and the northern Komi-Permians, i.e. those areas where contact with the Russian population was most intense. “In the rest of the territory, with a few exceptions, it was not practiced, and it is difficult to admit that it existed before, because there are neither people nor the memory of the local population about them,” notes G. N. Klimova. And then the researcher writes: “In the areas where typesetting weaving is spread, a number of facts indicate a relatively short period of this technique’s existence there… older women claim that in their villages red patterns began to spread abundantly only at the end of the 19th century. Fashion swept over everyone, and for there was not enough time for all women to master the basis of fashion”.

A. P. Kosmenko, speaking about the art of the Vepsians — settled in the north-eastern part of the Leningrad region, as well as in the north-west of the Vologda region, notes that at the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century, patterned weaving among the Vepsians was significantly inferior to the art of embroidery. She connects this with the fact that the patterned fabrics among them, in contrast to the Russians, “functioned poorly as objects of decorative design of the dwelling”. Further, A. P. Kosmenko writes that: “Vepsians have just started to get acquainted with labor-consuming and difficult-to-make patterns in two-day weaving on a large number of boards at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries… which was largely facilitated by red and white borders for decorative design of towels imported here from the Russians of the Vologda region, where this type of weaving was very developed”. Unlike Russian branched spacers, which had complex ornamental designs and high technique of execution, which testifies to the ancient tradition, the ornaments of Veps weaving items are simple, and the flooring of red threads forming patterns is not complicated, giving the impression of a factory product, like in Russians, but loose, which indicates a lack of technical development and the absence of deep traditions. A. P. Kosmenko notes that: “the red-and-white typesetting technique is not fixed in the weaving industry”, and further makes the following conclusion: “The Veps patterned weaving of the 19th and early 20th centuries does not apply such characteristics as"very developed”, types of decorative weaving prevail”, “more widespread than embroidery, or the same”. But all these characteristics exactly correspond to the level of development of typesetting weaving in the folk arts and crafts of the North Russian population in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

In his other work devoted to the folk art of the Karelians, A. I. Kosmenko writes that, despite the very high level of development of typesetting weaving in them, there is reason to believe that this type of weaving “is not as ancient as, for example, certain types of Karelian The ways of its distribution, obviously, are connected with more southern territories. Typesetting weaving prevailed in the regions of the most intensive contacts with the neighboring Russian population, — in southern and central Karelia. And finally, the Album of Khanty Ornaments (Eastern Group), compiled by N. V. Lukina based on museum collections and field materials of the author, is of some interest. The album contains about 900 ornaments made on birch bark and using the technique of fur mosaic. N. V. Lukina notes that embroidery with threads on fabric is more characteristic of the southern Khanty and now it is rarely found on tobacco pouches, handbags and cult objects, “woven patterns are very rare — on belts and garters of shoes”. Among the 900 ornaments listed in the album, very few have analogues in the North Russian brane weaving. These are “sart-pyonk” (pike teeth) and “tegor-pel” (hare ears) carved on birch bark, as well as patterns consisting of hooks and swastika forms (p. 178 (2) 0, 182 (5), 183 (3a), 208 (1,2,3b), 213 (Ia), 224 (2,3) Thus, only a little more than ten of 900 traditional Khanty ornaments can be correlated with the North Russian ones, i.e. almost a little more than 1 percent.

.

All of the above facts do not allow us to accept the hypothesis that the traditions of the Andronovo ornamental complexes came to the North Russian brane weaving from the Finno-Ugric population of the European north, who allegedly adopted them in ancient times from their Indo-Iranian neighbors.

Other options for resolving the issue of possible carriers of the ancient Andronov ornamental tradition are as follows:

The first is that the substrate population of the European North of our country before the arrival of the Slavs here was largely represented by the descendants of Indo-Iranian groups, as evidenced by the extremely archaic Indo-Iranian topo- and, especially, hydronymy of many regions of the Russian North. Being a substratum of the North Russian group of the Russian ethnos, they have preserved the ancient ornaments of their ancestors.

Second, since the Aryan population of the European part of Russia took part in the process of ethnogenesis of the Eastern Slavs, which did not participate in the movements of the Aryans in the middle of the 2nd — early 1st millennium BC tothe south and southeast, and did not leave these territories, then it is likely that the Andronovo ornamental complexes were also brought to the European north by the Slavs who came here.

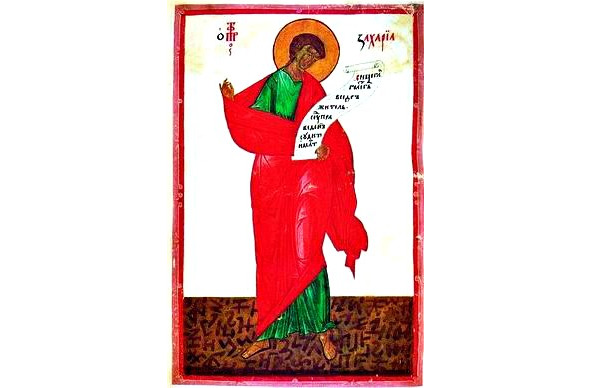

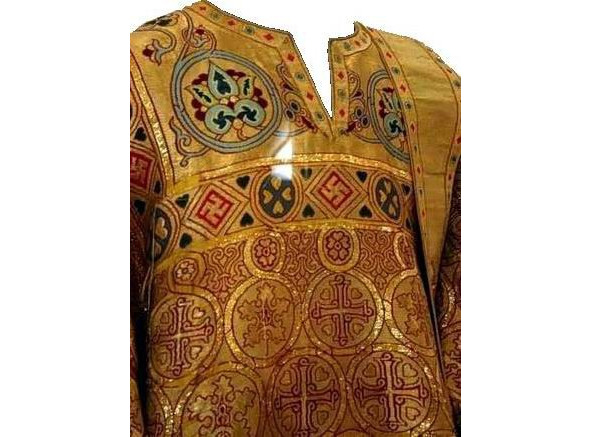

This is all the more likely that Andronovo-type ornaments are characteristic not only for typesetting weaving of North Russian peasant women, but are often found in embroidery, lace and typesetting in other Russian provinces of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. In addition, we can trace the existence of the Andronovo type ornament in the Russian, and more broadly, the East Slavic, tradition over many centuries. So G. N. Klimova, speaking about the traditions of the ancient geometric pattern, notes that they are “present” in the ornament of Russian gold embroidery of the 15—17 century, i.e. there is a stability of patterns of this type in Russia in the past four to five centuries. There is information that lowers their age to the 11—13th century”. Here it makes sense to refer to the materials published by N. A. Mayasova. Without much effort, you can see that most of the attire of the characters depicted in the facial sewing of medieval Russia is filled with rhombic, zigzag and meander patterns. So the meander braid fills the halos of the Mother of God and the saints on the shroud “The Appearance of Our Lady to Sergius” of the second half of the 15th century, the halos of Nikola and Nikola Mozhaisky on the shroud of the early 16th century, it adorns the robes of John the Baptist on the banner of the last quarter of the 16th century and the omophorion of Metropolitan Jonah in the 17th century sewing. Meander braids, rhombuses, crosses fill the clothes of the characters, architectural structures, and even manure on the veil of “Nikola with a Life” of the second half of the 17th century. It should be noted that it is on the last veil in the filling of some details — the clothes of Nikola and the walls of the temples — that the ancient Paleolithic rhomboeander ornament of the Mezin type is presented in its pure form. In the composition “Presenting the Tsarina” 1602 on the robe of the Mother of God are intricately drawn swastikas (Table 7), and on the shroud “Position in the Tomb” ornaments of the Andronovo type adorn the garments of angels, the Mother of God and even a horizontal stripe over the body of Christ. The background of one of the most ancient monuments of Russian facial sewing — the altar shroud of the 12th century made in Novgorod — is all filled with circles of “jibs”, a characteristic motif of Andronov’s ornamentation (Table 5). Not only in sewing, but also in other types of medieval Russian art, we find elements of the ancient Andronovo ornament. So on the ground of the 15th century miniature depicting the prophet Zechariah, made in Moscow, among the various signs are visible “jibs”, swastikas and various swastikas (Table 8). An interesting ornamental composition is presented on a slate spindle, found in a Slavic rural settlement of the 11—13th century near the city of Ryazan, in the area of the Pronskaya SDPP reservoir. On it we see an image that vaguely resembles an Orthodox cross and a human figure at the same time, because the upper and lateral ends of the cross end in tridents, very similar to the three-fingered hands, characteristic of the characters of the sacred circle since the time of Tripoli. This central link in the composition is surrounded by segments of meander spirals and swastikas (Table 9).

Motifs from simple and intricately drawn swastikas are placed as hallmarks on the bottoms of 11—12th century vessels found during excavations in Staraya Ryazan (Table 9).

Among the marks on the vessels of Smolensk (11—10th century), E.V. Kamenetskaya distinguishes, as the most archaic, the marks in the form of a swastika found on ceramics of the 10—11th century, and believes that they were cult among the Slavs, expressing deification and veneration of the sky, heavenly bodies and fire (Table 9).

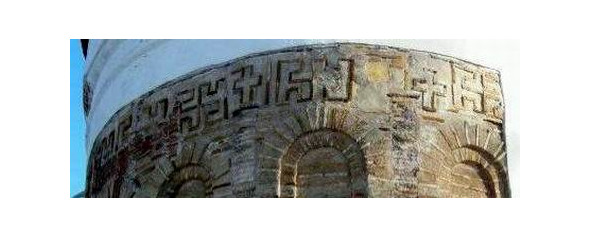

The swastika, as an element of decor, is found in brickwork and mosaics of the first Christian cathedrals of Kievan Rus. This is the main motive of the ornamental belt of the Eucharist composition of the apse mosaic of St. Sophia Cathedral in Kiev (11th century).

Of exceptional interest is the ornamental layout, which decorated the staircase tower of the Spassky Cathedral in Chernigov, one of the oldest structures in medieval Russia, the same age as the Kiev Sophia Cathedral (11th century). N.V. Kholostenko, who published these decorative displays, discovered after the removal of the late plaster, believes that such ornaments had a “special, symbolic meaning.” He notes that the particularly rich decoration of the staircase tower, distinguishing it from other parts of the cathedral, is due to the fact that it was the place of “the ritual entrance of the prince and his entourage to the choir.” (Table 10). In the second tier of the tower, there is a wide ornamental belt made up of alternating equal-pointed crosses and intricately drawn swastikas.

This shape of the swastika, with the ends curving in the form of a meander, was also given to the metal buckle 1220—1260, found at the Tikhvin excavation site in Novgorod (Table 10). It should be noted that this unusual and rather complex form comes unchanged until the 1910s, when a Vologda peasant woman Ulyana Terebova, making an abusive spacer for her daughter’s wedding towel (Table 10), ornamented it with just such meander crosses. Bone combs of the 9—10th century found in the burial mounds of the Suzdal Opolye and in the the lower layers of Staraya Ladoga. The swastika sign marks a clay spindle from a 7—8 century settlement on the Tyasmin River, which belongs to the ancient Slavic tribe of Ulitsy (Table 9).

Sinking further into the depths of the centuries, we find all the same meander and swastika motifs in the decor of the products of the Przeworsk and Zarubintsy cultures, which were widespread in the 3rd century BC. — 3rd century AD (according to B. A. Rybakov) in the same territories as the Proto-Slavic Trzhinets and Komarov cultures in the 15—12 century BC.

This is well illustrated by the materials presented in the work of A. L. Mongait, which shows various vessels of the Przewor culture, decorated with meanders and intricately drawn swastikas, and in the article by E. A. Symonovich, which also gives samples of meander-swastika decor (Table 11).

E. A. Symonovich in his work notes that the swastika, found on the vessels of the Bronze Age, “is widespread in purely Slavic patterns of the era of Kievan Rus, denoting the sign of the sun”.

And, finally, if we turn to the Scythian period on the territory of the Middle Dnieper region, which proceeded the time of the appearance of the Przhevorsk and Zarubinets cultures, then we will meet the same picture here. On vessels from the Dnieper forest-steppe, one of the most common ornamental-symbolic motifs was a swastika, both of a simple form and of a very complex pattern, with many hooks-appendages at the ends. Moreover, it is extremely interesting that one of the vessels of the 6th century BC from the excavations near the village of Aksyutintsy, next to an equal-pointed cross and swastikas of various shapes, a cross, significantly larger than their size, was placed, which from the beginning of the 2nd millennium AD will become an “Orthodox” cross in Russia (Table 11).

Thus, a continuous ornamental tradition can be traced, going from the cultures of the Bronze Age to Russian peasant embroidery and weaving of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. But since it is in North Russian weaving that the ancient Andronovo complexes are found in the most complete form, which the Finno-Ugric peoples of this region do not have, we can assume another solution to the issue of the carriers of the Andronov ornamental tradition.

It is possible that both the substratum population of the north of Eastern Europe before the arrival of the Slavs here, and the Slavs who came to these lands had similar sacral ornamental symbols, transmitted to them by their distant common ancestors. There was probably a certain awareness of this relationship.

Otherwise, it is extremely difficult to explain the clear direction of the mobile Slavs precisely in Zavolochye, to the East of the European North, noted by V. V. Pimenov in his work “Vepsa”, where he writes, that: “for some not entirely clear reasons, the bulk of Russian immigrants either, like the Novgorod ushkuyniks, passed away, almost without lingering and almost without settling, the indigenous lands of the Vepsians, or else she bypassed them altogether, directing her way directly to Zavolochye”, those on the land of the legendary “chudi white-eyed”, about which we spoke a little earlier.

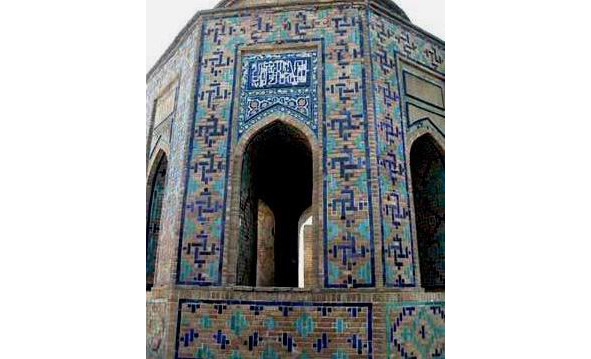

It probably makes sense to agree with V. N. Danilenko, who expanded the zone of accommodation of Indo-Europeans in the 8—5 thousand BC from the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea up to the watershed of the rivers of the White and Caspian Seas and further north, and assume that the substrate population of the Vologda lands, before the arrival of the Slavs here, was overwhelmingly represented by the descendants of this ancient Indo-European massif. Thus, it will be possible to explain the preservation in the North Russian tradition of such forms, which are completely uncharacteristic of the Finno-Ugric ornamentation, or are extremely rare in it, but at the same time they are constantly present in weaving and embroidery of the late 19th — early 20th centuries of the eastern regions of the Vologda region, on the one hand, and in the monuments of various archaeological cultures of the southern Russian steppe and forest-steppe, on the other. Ornamental complexes, identical to the North Russian ones, typical for the North Caucasus and some regions of the Transcaucasia, they are quite common in the mosaic decoration of medieval temples, mausoleums, mazars of Central Asia and Iran, those common in those territories which modern science associates with the Aryan advances of the late 2nd — early 1st millennium BC.

In the Bronze and Early Iron Age, the closest analogues of the Timber-Abashevo-Andronovo ornaments in the southeast of the European part of the country are found in the monuments of the North Caucasus of the second half of the 2nd — early 2nd millennium BC. These are, in particular, materials published by V. I. Markovin from excavations of the crypt of the 2nd millennium BC the village of Engikal in Ingushetia: plaques and pins with disc-shaped pommels, covered with punson swastika and meander-like images (Table 12). He notes that: “unfortunately, the North Caucasian ceramics of the Bronze Age has been poorly studied so far, almost no comparison has been made with the ceramics of the steppe cultures”, and at the same time: “… there is no doubt that it was the steppe tribes of the Lower Don that wedged themselves into the Kuban region”. Here we should once again recall the hypothesis of O.N. Trubachev that the Kuban people of the Sindi are a relic of the Indian tribes that remained in Eastern Europe after part of the Indo-Iranians (Aryans) left this territory. Among the materials published by R. M. Munchaev on the burials of the Lugovoy burial ground in the Assinsky gorge (Checheno-Ingushetia), a significant percentage of double-oval bronze plaques (it is interesting that the same form is characteristic of Slavic brooches of the 8th century), marked with a swastika, punched in the center of each oval. R. M. Munchaev notes that: “… they were always near the skull or chest.

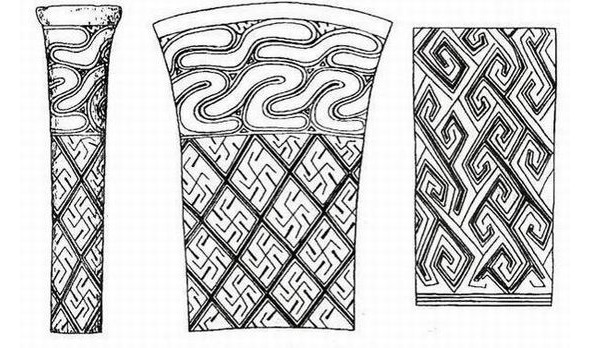

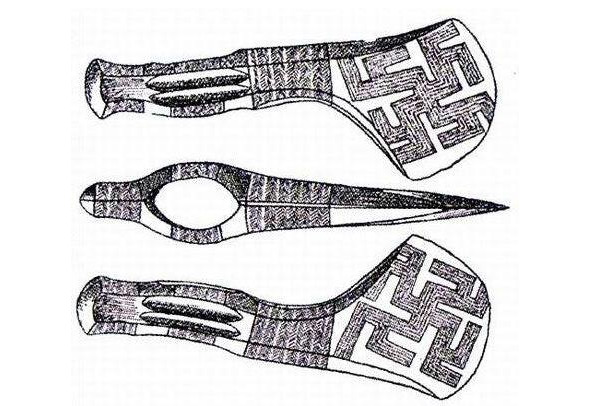

This allows us to consider them as forehead or breast plates”. Interestingly, burial grounds such as Lugovoy and Nesterovsky, also located in the Assinsky gorge, are characterized by the erection of burial mounds over burials. All this is very similar to the traditions of the Andronovites, as well as the obligatory presence in the burials of vessels and ornaments, and on the latter, as we can see, ornamental motifs were placed, more than traditional for the Andronovo monuments. Similar functions of amulets as double-oval plaques from the Lugovoy burial ground, plaques and pins from Engikal, were probably performed by the forehead corollas-diadems of the 14—13th century BC, found by B. V. Tekhov during excavations of the Tli burial ground in South Ossetia. These tiaras are decorated with geometric shapes — circles, triangles, rhombuses, and, as a rule, meander and swastika images (Table 12). B. V. Tekhov notes that similar diadems were found in one of the Styrfaz cromlechs (North Caucasus), in the village. Gegharot (Armenia), on the territory of Azerbaijan and Iran. It is interesting that the continuous pattern formed by swastikas on some diadems (Table 11) is absolutely identical to the ornamental motif characteristic of the Slavic Przewor culture of the 3rd century BC. — 3rd century AD (Table 11) and repeated on a Russian tile of the 18th century (Table 11). The meander and swastika motifs on the bronze axes of the Koban type from the same Tli burial ground are also of exceptional interest. Intricate swastikas placed on these axes from the 12th-9th century BC have analogues in the ornamentation of Pozdnyakovsk vessels, culture of closely related and simultaneous Andronovo.

For example, a swastika with numerous “shoots” at the ends, placed on the bottom of one of the clay pots found in the Pozdnyakovsky burial ground “Fefelova Bora” (Ryazan) (Table 12), is repeated with each line on Koban bronze axes (Table 13). But we see such precisely complexly drawn swastikas on one of the maces of the crypt near the villages. Engikal (Table 12), they are present in the ornamentation of finds from a number of places in Azerbaijan, for example, on a clay stamp, as well as on the walls of the temple, the plaster of the dugout and the pintadere (Table 12), on the wall near the hearth and pintadera of the village of Babadervish (Table 1. 12). The same intricate swastika adorns the Koban buckle of the 6—5th century BC (Table 12) and a Scythian vessel from the 6th century BC from the village of Aksyutintsy on the forest-steppe left bank of the Dnieper (Table 12). The most complex swastika braid, carefully crafted by a master of the 9—7th century BC on one of the Koban bronze axes (Table 7), without the slightest changes, it is repeated in the Russian facial embroidery — the pattern of the royal robes of the Mother of God of the above-mentioned composition “Appearing the Tsarina” (Table 7) and in the embroidery of the Olonets valance of the 19th century (Table 7).

And, finally, almost any, the most complex and whimsical branched swastika pattern, we can easily find among the samples of weaving and embroidery of Vologda peasant women of the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

It could be assumed that all these ornamental motifs came from Byzantium into facial embroidery, which adorns religious objects associated with Christian rituals and from it to peasant embroidery and weaving. But there are no such compositions in the Byzantine tradition, which is clearly evidenced by the samples of ornaments published by V.V. Stasov in the album “Slavic and Oriental Ornament Based on the Manuscripts of Ancient and Modern Times”. And at the same time, in medieval psalters, gospels, books of hours, etc. Russia, Armenia, Serbia, Croatia, many elements of Andronovo and Koban decor is constantly present, and, in particular, such characteristic motifs as swastikas of various configurations, jibs, meanders, triangles. They are found to this day in folk ornamentation in the North and Central Caucasus, on the western coast of the Caspian Sea, in Armenia and Azerbaijan.

It could be assumed that all these ornamental motifs came from Byzantium into facial embroidery, which adorns religious objects associated with Christian rituals and from it to peasant embroidery and weaving. But there are no such compositions in the Byzantine tradition, which is clearly evidenced by the samples of ornaments published by V.V. Stasov in the album “Slavic and Oriental Ornament Based on the Manuscripts of Ancient and Modern Times”. And at the same time, in medieval psalters, gospels, books of hours, etc. Russia, Armenia, Serbia, Croatia, many elements of Andronovo and Koban decor is constantly present, and, in particular, such characteristic motifs as swastikas of various configurations, jibs, meanders, triangles. They are found to this day in folk ornamentation in the North and Central Caucasus, on the western coast of the Caspian Sea, in Armenia and Azerbaijan.

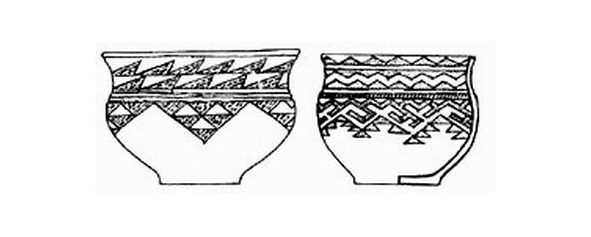

In practice, the spread of the Andronovo circle ornaments is one of the most important indicators of the ways of promoting the agricultural and cattle breeding tribes of Eastern Europe in the Bronze Age and the Early Iron Age. So M. N. Pogrebova notes that white-encrusted ceramics, the striking similarity of which with the cut ornament of the Andronov culture has been repeatedly drawn by researchers, appears in the Eastern Transcaucasia in the second half of the 2nd millennium BC “in its current form with very rich and varied motives. She believes that in the addition of the Iranian material culture itself, newcomers from the steppes and forest-steppes of Eastern Europe played, apparently a significant role, as evidenced by archaeological sites of the early 1st millennium BC and, in particular, ceramics from Iran showing Andronovo influence, decorated with triangles and meanders, the meander being the leading ornamental motif (Tables 2, 3).

In practice, the spread of the Andronovo circle ornaments is one of the most important indicators of the ways of promoting the agricultural and cattle breeding tribes of Eastern Europe in the Bronze Age and the Early Iron Age. So M. N. Pogrebova notes that white-encrusted ceramics, the striking similarity of which with the cut ornament of the Andronov culture has been repeatedly drawn by researchers, appears in the Eastern Transcaucasia in the second half of the 2nd millennium BC “in its current form with very rich and varied motives. She believes that in the addition of the Iranian material culture itself, newcomers from the steppes and forest-steppes of Eastern Europe played, apparently a significant role, as evidenced by archaeological sites of the early 1st millennium BC and, in particular, ceramics from Iran showing Andronovo influence, decorated with triangles and meanders, the meander being the leading ornamental motif (Tables 2, 3).

A similar picture can be traced in the ornamentation of Central Asia in the late 2nd — early 1st millennium BC. M.A. Itina, on the basis of studying the materials of the Khorezm exposition, concluded that complex ethnocultural processes took place here in the Bronze Age. The steppe bronze culture discovered in the South Aral region on the territory of the Akcha-Darya delta of the Amu-Darya, named by S. P. Tolstov as Tazabagyab, and has stucco ware with geometric Andronovo type ornaments. M.A. Itina writes: “The presence of the Timber and Andronovo features in the Tazabagyab culture gives us grounds to speculate about the alien character of the Tazabagyab population of Khorezm.”

She also notes that the similarity of the ceramic material of the Bronze Age from the steppes of the Middle Volga region and Western Kazakhstan with Khorezm was more than once written by I. V. Sinicin. M.A. Itina believes that not only archaeological material makes it possible to record the advancement of pastoralist tribes from the northwest along the channels of the Uzboy, Atrek, Tejen, Murgab, Amu-Darya, Syr-Darya rivers, but also anthropological data record “a broad advance of the so-called Andronovo type to the south”. She subscribes to the opinion of S. P. Tolstov that the tribes of the Tazabagyab culture were “the first significant wave of Indo-European, Indo-Iranian or Iranian tribes that penetrated into Khorezm from the northwest”. I. M. Dyakonov believes that the path of the Aryan tribes from their ancestral home ran along the foothills of the Kopet-Dag, where there is “an ecologically uniform strip connecting Hindustan and the interior regions of Iran with Central Asia”. The same conclusion about the advance to the territory of Central Asia and further to Afghanistan and India of the northwestern pastoralist and agricultural tribes in the middle of the 2nd millennium BC does also V. I. Sarianidi. He notes that defensive fortresses with powerful walls and angular towers appear almost simultaneously in the Murghab basin (Auchin, Gonur), southern Uzbekistan (Sapali-Tepe), northern Afghanistan (Dashly I), “which excludes the element of chance and, on the contrary, acquires the features patterns due to the resettlement of tribes with general cultural unity”.

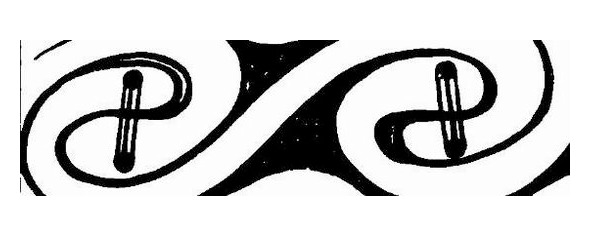

V. I. Sarianidi compares the seals-amulets of Murghab (Southern Turkmenistan) of the middle of the 2nd millennium BC with the Near East and concludes about their independent origin. Speaking about the ornamental motif in the form of a swastika (“viper knot”), characteristic of Murghab seals, he comes to the following conclusion: " It seems that this specific drawing is more inherent in Iranian than Mesopotamian art: in this case, the Murghab image… most likely of Iranian origin,” and “only in the Iranian world do we meet scenes approaching the drawings of the Murghab seals”. We, in turn, can add to the above that K. Humbert in his album of 1000 ornaments of various peoples of the world defines the braid in the form of a “viper knot” as characteristic of the Iranian and Indian traditions.

But such an ornamental motif is often found in the decor of medieval miniatures of Russia, as evidenced by the materials of V. V. Stasov’s album, for example, the headpiece of the Gospel 1409 of the Pskov work (Table 14), the miniature of the Psalter of the Konevsky Monastery, made in the 14th century in Novgorod (Table.15), a sample of ornaments from Ryazan, Galich, Vologda 14—16th century. In addition, the “viper knot”, which was so characteristic of the Iranian tradition of the mid-to-late 2nd millennium BC, is present in the embroideries of various provinces of Russia until the late 19th and early 20th centuries. It decorates, as the main ornamental motif, a fly of the 17th century, embroidered spacers of the late 19th century in the Tambov and Voronezh provinces and Kirillovsky district of Novgorod province.

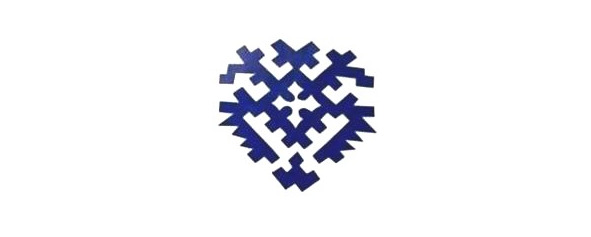

V. I. Sarianidi notes that with the spread of new types of seals, the practice of making anthropomorphic sculptures completely ceases in southern Turkmenistan and the Indus Valley, which indicates changes in the ideological ideas of the local population, and that many authors see new Indo-European tribes in the carriers of the Dzhukar culture Indian subcontinent. This is how R. Heine-Geldern and V. Ferservice identify the Djukarts with the Arias, and G. M. Bongard-Levin believes that: " the emergence of the Djukar reflects the penetration of a small group of tribes associated with Baluchistan into Sindh”. One of the most important proofs of the Aryan invasion is considered the seals from the Chankhu-Daro hill, which are sharply different from the Harappan seals proper and have analogues only in the Indus Valley, Southern Turkmenistan, Northern Afghanistan, Susiana. Of exceptional interest in the light of our problems is the discovery by the Soviet-Afghan expedition (under the leadership of V. I. Sarianidi) in Northwestern Afghanistan, northwest of Balkh, of a monumental complex, defined by V. I. Sarianidi as a “temple city” of the Bronze Age. K. Yettmar suggests that both the circular fortification with nine towers and the surrounding buildings Dashly 3, subordinated to a certain religious idea, were used only during the annual holiday period. He notes that memories of such ritual centers are preserved in both ancient Indian and ancient Iranian texts. In addition, the mythology of Nuristanis (Kafirs of the Hindu Kush) contains indications of the “heavenly castle” where the souls of the dead find shelter. Descriptions of such a castle are in many ways reminiscent of structures in northern Afghanistan. K. Yettmar believes that the analogies of the “temple city” of Dashly 3 in the steppe zone were Koy-Krylgan-Kalu and the Arzhan mound in Tuva. E. V. Antonova, analyzing the layout of the structures of Dashly 3 and Sappalli-Tepe (Southern Uzbekistan) and noting the presence of geometric shapes in their outlines, he writes: “The fact that the planning of structures was given special importance is also evidenced by the amazing closeness of the plans of several buildings of the Late Bronze Age with ornamental motives”. V. I. Sarianidi notes the unusual layout of the so-called “palace” Dashly-3 and considers the T-shaped, extremely narrow corridors, in which it is difficult for even one person to pass, very indicative. “It seems that they had a” false “character, did not carry any functional load, were the architectural and ritual canon that should have been unswervingly present in monumental buildings of this purpose”. We can state that the plan of the “palace” Dashly-3 (Table 16) is traditional, one of the most widespread, along with the swastika, elements of Russian weaving, the so-called. “rhombus with hooks”, the semantics of which is devoted to one of the works of A. K. Ambroz.

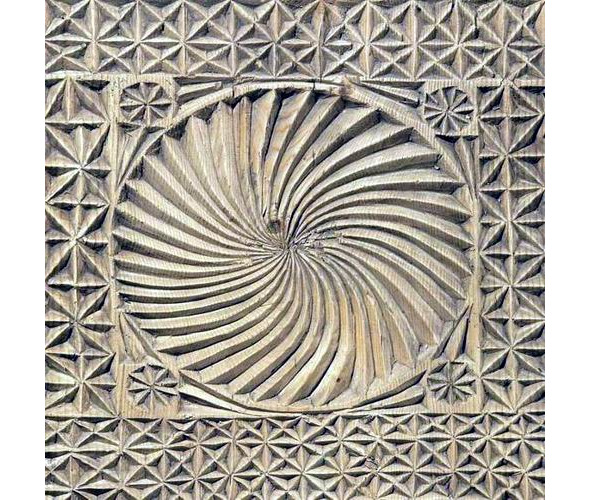

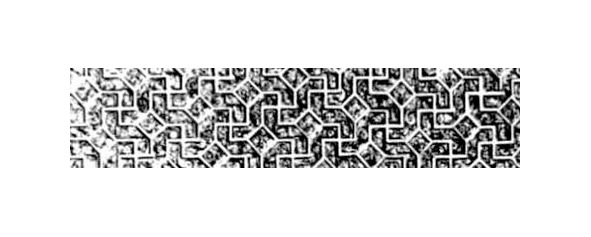

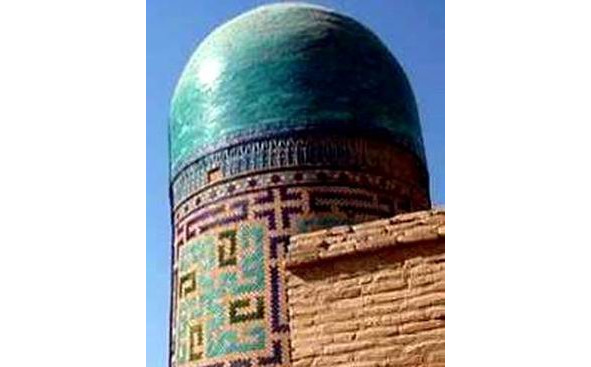

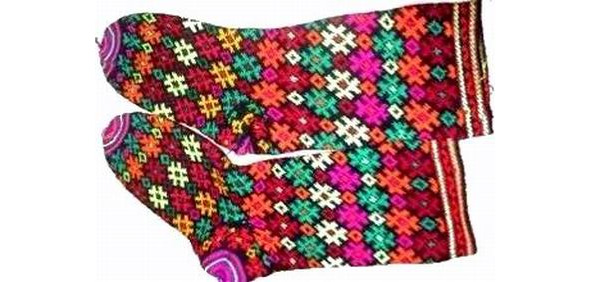

In Dashly-3, the “rhombus with hooks” is supplemented by T-shaped processes on the sides of the rhombus, which are also often found in rhombic compositions of North Russian ornamentation (Table 16). E. V. Antonova notes that the plan for the construction of the central part of Sapalli-Tepe becomes similar to the swastika. But such a swastika also has analogues in weaving and embroidery of the Vologda peasant women of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. As noted earlier, most researchers associate the appearance of ornaments of the Andronovo complex, and in particular, meanders, swastikas, etc., in Central Asia, Afghanistan and Hindustan in the late 2nd — early 1st millennium BC with the advance of the Aryan groups to these territories from the northwest. About how significant these ethnic shifts were, and what a serious change in ideological ideas they brought with them, is evidenced to a large extent by the fact that many of the archaic ornaments brought to Central Asia, Afghanistan, Hindustan by the northern steppe tribes, survived in this region to our time. So M. Ruziev in his work dedicated to Tajik woodcarving, writes, that in the design of the doors and gates of Bukhara, an important role is played by the geometric ornament that took shape in the pre-Muslim period, consisting of zigzags, rhombuses, squares, swastikas. Moreover, he attributes the swastika to the most ancient and stable motives of a geometric pattern. “It is found in various types of decorative arts — tiled decoration, paintings, embroidery, carpets… In Central Asia, this ornamental motif can also be found on knitted Pamir stockings, in carving on tombstones, carving and painting on ganch and wood, and glazed architectural ceramics. The swastika figured in the decoration of the brick floors of ancient Khuttal and on the ganch panels of the palace from Afrasiab (10—11 century).

On the carved doors of Bukhara dwellings, it often appears not only as an ornamental motive, but the door frame was also constructed from it…”

It should be remembered that the swastika is present in the decor of Shahi-Zinda (14th century), Bibi-Khanum (14th century), El-Registan (15—17th century) in Samarkand.

The ancient traditions of Aryan ornamentation were especially stable in the art and architecture of the Pamiris, where they survived to this day, which was facilitated by the disunity and inaccessibility of mountain villages, a patriarchal way of life and the fact that for more than two millennia the population here did not practically change.

The common origins of both the East Slavic, in particular the North Russian, and the Mountain Tajik (i.e., East Iranian) ornamental tradition are evidenced not only by works of applied art of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, but also by archaeological materials; so, for example, intricately drawn swastikas on a clay carved mazar Mavlono Muhammad-Ali 10—12 century find an analogy in the drawing of a stamp on the bottom of a vessel from the 11th-12th century from Staraya Ryazan.

As for such archaic, dating back to Andronovo, ornaments on the other side of the Pamirs, on the territory of Hindustan, it is well known what a huge role the swastika plays in the rituals, ceremonies, and decor of India — a symbol of the sun, eternity, and happiness. M. Ruziev, noting that the Central Asian swastika compositions are related to the ancient Indian ones, focuses on the ancient tradition, following which on the day of the Yatra holiday, the brahmans in desert places arranged large sacrificial fires, each of which consisted of four swastikas.

It must be said that such compositions of four swastikas, grouped around a common center, are characteristic not only of ancient Indian, but also of both the South Russian (Tambov, Voronezh, Kursk, Ryazan) and North Russian traditions.