Бесплатный фрагмент - Hyperborea and the Aryan ancestral home

Natural-scientific aspects

Russia is a country of eternal changes and completely non-conservative, it is country beyond conservative customs, where historical times live, and do not part with rituals and ideas. The Russians are not a young people, but the old ones — like the Chinese. They are very old, ancient, conservatively preserved all the oldest and do not refuse it. In their language, their superstition, their disposition, etc., one can study the most ancient times.

Victor von Hyun. 1870.

Should we be afraid of climate change?

Many years ago, in the smoking room of the Vologda Museum of Local Lore, S.V. Zharnikova, a person in the museum who was unloved for freethinking and oppressed by the director Novozhilova (the grandmother of the famous Vologda showman Kirill Panko), spoke about the impending global warming based on the historical experience of 5,000 years ago.

Then the climate in the Northwest was akin to what is now in western Ukraine, in Poland and the Czech Republic. Deciduous forests grew everywhere, inhabited by deer, bison, and, they say, even some varieties of large feline predators. Here lived the ancient Indo-Europeans, who are usually called arias.

Zharnikova said that there was a climatic optimum. Then came the cooling, not immediately and suddenly, but gradually the climate began to change in the direction of the cold. Deciduous forests were replaced by conifers, and even further north by the «white-fronted sea», where the forests used to grow, the tundra appeared. The species composition of life has gradually changed.

The Aryans also left here and settled widely on a vast territory from the Baltic to India, preserving in the legends and monuments of folklore information about their northern ancestral home. Others came to the liberated territories — Finno-Ugric tribes. At the end of the first millennium of a new era, a part of the Indo-Europeans — Slavic tribes returned to the north, assimilated or mixed with the local Finno-Ugric peoples (alright and all) and gave rise to the modern population of the North of Russia.

They did not believe Zharnikova, she studied the ornaments of some village towels, the names of tracts, rivers and lakes, compared them with the names of Southern Europe and Northern India and found parallels. Some allowed themselves to laugh openly at the arguments of the researcher…

A little over 30 years have passed. Svetlana Vasilievna is no longer with us, but her lectures on the Internet, articles and books have made in the public mind a researcher with a modest academic degree, Academician, unquestioned authority in the field of ethnography.

The climate is also changing, we are predicting low snowy warm winters, scare, shout about the death of the northern fauna. But is it really bad when there are no 30-degree frosts, fruit trees do not freeze, and forest dwellers do not die from a nonsense.

As for the polar bears, the Arctic is great. The benefits of warming are much greater. You will talk about the cold summer of last year. This is a reality, forests are cut down, winds from the north rush non-stop to the Ural Mountains. This is certainly bad… But man is to blame for this, not nature.

We conclude that a warm winter is not a reason to be upset, but those who miss the frost and huge snowdrifts can be moved to Vorkuta, Yakutsk or other places where everything is in order with this matter.

Indo-Europeans: Paleoecology and Natural Plots of Myths

For more than a hundred years, scientists have been investigating the problem of the origin of Indo-European peoples. However, there are still too many unresolved issues: «Those constructions on ethnogenesis that scientists arranged to some extent several decades ago now no longer satisfy ethnogenetic science,»

wrote a few years ago, the Soviet archaeologist V. V. Sedov wrote about the current situation in Indo-European studies.. And what is proposed to be considered in this article is also, of course, preliminary. Rather, it is a material for reflection.

Since the processes of ethnogenesis occur in a specific environment, there can be no doubt that much valuable information about the past of ethnic groups is captured in the annals of natural phenomena. The attraction of data from the natural sciences should, to some extent, revitalize ethnogenetic research.

The consequences of environmental crises on the Russian Plain

In recent decades, environmental advances have forced a new interpretation of some aspects of the life of primitive man. Sections that study the flow of energy in ecosystems, the growth and regulation of the number of populations, and successions help to comprehend the ethno genetic processes of the past. At the same time, one should also keep in mind such an important regularity that A. A. Velichko recently again paid attention to: the deterioration of the ecological situation stimulates the process of anthropogenesis. This allows you to better understand the possible causes of spasmodic shifts in the development of humanity. A radical change in the natural environment in the Late Glacial period, primarily the excessive extermination of large mammals, led to an environmental crisis in the Upper Paleolithic. In response to this challenge of nature, man learned to hunt small, non-gregarious game (bows and arrows were invented), created a higher — Mesolithic culture.

A significant cooling of 4.6 — 4.1 thousand years ago led to the spread of conifers on the Russian plain by reducing broad-leaved. This led to a reduction in the number and diversity of herbivores, since coniferous forests are poor in grass and shrubs, and, as a result, in a new environmental crisis. Herbivores use 1.5—2.5% of the net primary production of mature deciduous forests, about 12% — fallow lands, 30 — 45% — cultural pastures. Ethnographic studies have shown that primitive people noticed this already at the level of the Stone Age cultures and began to reduce woody vegetation with the help of fire long before the formation of slaughter agriculture.

On the Russian Plain, an environmental crisis manifested itself on the eve of the livestock era, when the migration of people to these regions from the south intensified. Trying to overcome the consequences of this crisis, the then local hunter had to artificially maintain the productivity of forest ecosystems, thereby preparing himself to become a breeder. And for this it was necessary first to learn how to increase the reserves of wood (young twigs) and grass feed. In this case, the local hunter was much more experienced than the shepherd who migrated here from the Black Sea steppes, who also underwent a kind of «cultural regression» from the Eneolithic to the Neolithic when moving to the forest zone. The initial phase of the sub-Atlantic period 2.5—1.8 thousand years ago on the Baltic plains was characterized by deterioration in climatic conditions, which led to the decline of agriculture and related grain farming.

Its new rise became possible here only after local farmers «re-educated» the weed-field rye and it became the main cereal in central Russia. This happened already at the time when Roman civilization was flourishing, which, however, did not have any noticeable effect on the economic development of the Baltic countries.

Any advance of «southerners» to the north (in this case by «southerners» we mean not only people, but also cultivated plants, domestic animals) was accompanied by a long period of acclimatization. Not all people, not all species of flora and fauna have overcome the climatic barrier. Not all immigrants from the Black Sea-Caspian steppes were able to develop the already populated forest zone and assimilate the indigenous population.

What are linguists talking about?

Ethnogenetic constructions based on linguistic data usually end with the geographical localization of the identified linguistic communities. Often this problem is solved too straightforwardly. In linguistic literature, it is regularly noted that among the Indo-European languages, the Baltic languages are richest in archaic elements (phonetic, morphological, and lexical). In this regard, some scholars consider the Baltic languages to be less distant from the Indo-European parent language: this point of view is reflected, for example, in the model of the interconnections of Indo-European languages, in the centers of which are the Baltic languages. There are even sharper opinions: considering the Lithuanian language as the most archaic, such scholars argue that Lithuania is the ancestral home of the Indo-Europeans.

It goes without saying that linguistic archaisms individually cannot be reliable witnesses to the fact that their speakers are the indigenous (autochthonous) population of the region in question. However, the question of how and why such a language survived in the Baltic States remains unanswered. Nevertheless, now, when carved hypotheses arose of localizing the ancestral home of the Indo-Europeans, it is becoming especially relevant.

At one time, a famous scholar of the history of Indo-Europeans O. Schroeder tried to solve this question, which collected a lot of linguistic material. In his opinion, «the initial limits of the originally Indo-European territories… and the place of the outcome of the Indo-European folk should be sought within the boundaries of a certain land complex, stretching in a narrow land strip from the Rhine to the Hindu Kush. ...In connection with the more widely developed terminology of forest species of birds, salt, pig breeding in the vocabulary of European languages, I am inclined to think that… the features of each group (in the specific vocabulary of Indo-Europeans of Europe and Indo-Iranians) reflected contrasts of the forest and steppes, found only once in a rather sharp form and size, throughout the entire belt noted above: namely, north and northwest of the Black Sea.» Such a statement, however, would be more convincing if the paleogeographic data confirmed that in the indicated region during the collapse of the Indo-European praetnos, the forest really coexisted with the steppe.

Apparently, the ethnogenetic hypothesis of A. A. Shakhmatov is also worth recalling. In 1916, he wrote: «… the ancestral home of the Indo-Europeans should be attributed to such a place in Europe, where there were conditions for the formation of a more or less integral culture… The original homeland of the Indo-Europeans was located north of the Mediterranean cultural centers. Most likely, we should look for her in Central Europe, perhaps in modern southern Germany and the western regions of Austria. … Over time, the eastern branch of the Indo-Europeans, apparently the ancestors of the Iranians and ancient Indians, broke up… the original territory of the eastern Indo-European tribes, including the ancestors of the Slavs, was Northwest Russia, the Baltic Sea basin. I see confirmation of this in the fact that the Baltic people are still sitting on this territory, and we don’t have any evidence that they are not autochthonous here, that they came here from the south, from southern Russia… movement Aryans from the borders of Europe find a satisfactory explanation precisely under this assumption.

More than 70 years have passed since the publication of the Shakhmatov hypothesis, which was extremely rational from an ecological-paleogeographic point of view. Now a similar point of view is again beginning to attract the attention of scientists.

Of all the currently known geographical localizations of the ancestral homeland of the Indo-Europeans on the basis of linguistic materials, the latest scheme proposed by T.V. Gamkrelidze and V.V. Ivanov should undoubtedly be considered the most thorough. Its linguistic basis is favorably supported by paleobotanical, biogeographic, paleozoological data; Support for geographical localization of the ancestral home of the Indo-Europeans is landscape landmarks.

«The first thing that can be argued with sufficient certainty regarding the Indo-European ancestral homeland is that it was an area with a mountainous landscape…» the authors emphasize. «This picture of the pra-Indo-European landscape naturally excludes those flat areas of Europe where there are no significant mountain ranges, that is, the northern part of Central Eurasia and all of Eastern Europe, including the Northern Black Sea region.»

As you can see, this scheme completely refutes the previous one! And yet, in our opinion, to abandon it until all its aspects have been studied — not only linguistic ones — are early. Apparently, nevertheless, in the studies of ethnogenesis is a theory that is fruitfully developed by ethnographers. Yu. V.

Bromley, for example, believes that it is advisable to «consider an ethnic group and its environment as certain integrity — an ethno-ecological system.» Actually, our task is to study the paleoecological situation, which does not, however, claim comprehensive coverage of the issue.

Warming results

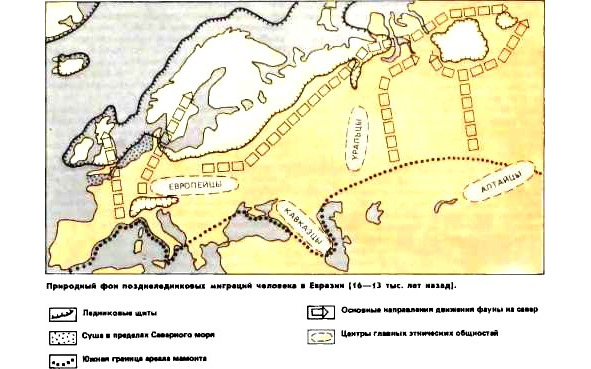

According to A.A. Velichko, during the maximum of the Valdai glaciation’s (20—18 thousand years ago), the territory between the Scandinavian ice sheet and the Pyrenees, Alpine, Carpathian Mountains were one natural zone. Under these conditions, there was no clearly coordinated seasonal migration of fauna, animals that were the object of hunting, wandering in search of food any season of the year in various directions. Such haphazard «migrations» of animals contributed to the fact that ethnic uniformity was maintained at the ice border from the Atlantic Ocean to the Ural Mountains.

On the eve of the degradation of the ice sheets, the nature of atmospheric circulation changed, the boundaries of new natural zones outlined in connection with this, unsystematic migrations of the Pleistocene fauna were replaced by purposeful seasonal migrations from glacial tundra to more remote forest areas and vice versa. Paleozoologists claim that clouds of harmful insects forced animals to seek refuge at the edge of the ice sheets. Archaeological finds of the Hamburg culture in the thickness of moraine loam near Lübeck (Germany) undoubtedly indicate that hunters of that time also appeared there.

In late glacial Europe, the formation of seasonal fauna migration paths was dependent on the southern ledge of the Scandinavian ice sheet, and then the southern outflow of the Baltic reservoir. This wedge could well contribute to the fact that the once united ethnic community was divided into two main parts: — western and eastern. This assumption is confirmed by archaeological data. The second half is the maximum largest leveling of the primitive economy from the Atlantic to the Urals, and later (12—10 thousand years ago) two distinctive provinces stood out in this territory — with the Azilian (early Mesolithic) culture in the West and a group of close archaeological cultures in Central and Eastern Europe.

To the west of the Baltic wedge, seasonal migrations of the fauna occurred south-north. Due to the gradual displacement of the border between the forests, they appeared to be at an impasse on the British Isles and on the Scandinavian Peninsula. The West European hunter could not but adapt to such migrations. Once upon a time, the areas of new ethnic communities stretched from south to north were to be laid down: one from Central France to Scotland, and the second from the Alpine foothills to Northern Scandinavia.

On the other side of the Baltic glacial wedge, seasonal migrations had a direction from south-east to north-west, and their routes slowly shifted to the northeast. The Pleistocene fauna of Eastern Europe had a free path to the North and even to Siberia, bypassing the Ural Mountains. The northern part of the Russian Plain during the degradation of the ice sheets for another three millennia (16—13 thousand years ago) was in a semi-closed position. From the northwest it was protected by the Scandinavian ice sheet, from the north — Novaya Zemlya, and in the east the Ural ridge rose. In this cauldron, large mammals and their persistent pursuers retreated northward. Therefore, it was here that the isolation of a new ethnic community could begin.

Later, a corridor between the Ural Mountains and the Arctic Ocean, through which animals penetrated into Siberia, was released from under a continuous ice sheet. Following them, a certain part of the population of the North of the Russian Plain could also have drifted there.

In the Late Glacial in the expanses of North Asia, natural zones were also restored and seasonal migration routes formed. Fossil remains of the fauna indicate that huge herds of mammoths still grazed in Eastern Siberia about 12 thousand years ago. Nearby was a man.

The patterns of animal migration leave no doubt that in the late glacial period on the treeless expanse of Siberia people of different ethnic groups constantly met. They could not but exchange economic skills, cultural values, lexical borrowings. The late glacial treeless populated part of Asia was quite suitable for anthropological and ethnic mixing. This representation is reliably certified by archaeological data. A.P. Okladnikov wrote: «At the end of the ice age and at the beginning of the post-glacial era, about 15—10 thousand years ago, east of the Urals, throughout the territory of North Asia… there was the same way of life of stray people, or, half-wandering hunting tribes… Paleolithic people at the same time entered here not from any center, but from various regions of Europe and Asia, primarily from glacial Europe.»

11 thousand years ago came the last significant cooling during the Valdai glaciations. By that time, there were no more mammoths in the Far North either; the number of other large mammals was significantly reduced. The then main inhabitant of the tundra — the reindeer — began to shift south. The vast majority of hunters of Arctic Eurasia had to move in the same direction along the river valleys.

As a result, reindeer hunter cultures have flourished on the plains of the middle belt of Europe.

After several centuries, 10.3 thousand years ago, the last cold period of the Late Glacial period was finally replaced by a warm one. The temperate zone of Europe was soon covered with continuous forests. The new environmental situation no longer caused significant relocations of human communities. Further natural factors (for example, transgression of the Baltic Sea 7.5 — 7 thousand years ago) predetermined migrations of only a partial nature. In the northern half of Europe, covered with impassable forests and swamps, tribal communication was significantly complicated. The time has come for the fragmentation of ethnic communities.

What are myths talking about?

Information hiding in traditions, legends, and myths is still little used to study ethnogenesis, although some of their elements have long attracted the attention of many researchers.

Indo-Iranian myths are particularly rich in natural subjects, in particular the myths of the main monument of ancient Indian writing — the Rigveda. The heroes of these myths originally lived where the sun did not set for six months, and then did not rise for the same amount of time, where very slippery mountains rose, and nature abounded with a variety of game. Later, myths testify, in those parts the cold intensified, the trees and grass stopped growing, the «hunting» animals disappeared, and when the water turned to stone, people were forced to leave that fertile land and retreat south along the river valleys. The Indo-Iranian peoples have long lived in the southern regions of the Northern Hemisphere, far from the Arctic Circle, and the mystery seems all the more mysterious — how did the Arctic plots appear in the creation of myths by Indians and Iranians?

The Indian scientist B. G. Tilak was the first to start a thorough study of the genesis of the natural plots of the Rigveda. In 1903 he published his famous work, The Arctic Homeland in the Vedas. His main conclusions: the heroes of the Rigveda lived in the warm interglacial beyond the Arctic Circle, while the new offensive of the glaciers forced them to move south; the position of the stars in the high latitudes of the Northern Hemisphere about 10 thousand years ago according to the Rigveda and according to astronomy is the same. It is significant that Tilak, still not knowing anything about the climatic dissection of the Late Glacial period, comparatively «fell» into the cold period of time.

This mysterious problem is also being investigated by Soviet scientists. Orientalists G.M. Bongard-Levin and E.A. Grantovsky came to the opposite conclusion: the authors of Indo-Iranian myths did not need to dwell on the Arctic Circle, they borrowed Arctic plots from foreign northern neighbors, and this happened on the Russian Plain. The scientific work of Bongard-Levine and Grantovsky is distinguished by a close systematic generalization of the natural plots of all Indo-Iranian myths and thus represents a valuable basis for paleogeographic consideration.

According to Indo-Iranian myths, mountains Meru and Khara once stretched from west to east throughout the north. An important detail: in the most ancient Indian texts Mount Meru is still a long ridge, and in a later one there is already a separate peak «covered with gold». What are the realities underlying this story?

These mountains cannot be the Ural and Scandinavian ranges, since they are stretched from north to south and not from west to east. The mountain ranges of the middle belt of Eurasia do not have polar days and nights. In addition, over the past millennia, these ridges have remained unchanged. The mythical mountains Meru and Hara are, most likely, the mountainous edge of ice sheets, impressively rising from the British Isles to the Urals. In the Late Glacial, long ice ridges disintegrated into residual blocks (peaks), on which, as the ice melted, the moraine was layered. It was she who could give that golden brilliance, which myths mentioned. After the blocks of the so-called dead ice completely melted, the sediments were on the ground, covered with vegetation and the unique sight disappeared without a trace.

Indo-Iranian myths are unanimous in that all rivers originate from the high mountains of Meru and Khara: they flow from ponds located on them or at their foot. That was exactly what happened in the Late Glacial on the Russian Plain — glacial ponds were the source of the main rivers.

Zoroastrian texts narrate that many «golden channels» flowed into the lake at the top of the Khara. This plot is an accurate picture of the formation of subglacial reservoirs. The «golden channels» of the Indo-Iranian mythical rivers were undoubtedly identified with the constant strata of water-glacial deposits, which in the Arctic climate were enriched with limonite, aqueous iron oxide and therefore had a yellowish-brown (golden) color.

Judging by myths, amazing life was in full swing at the northern mountains. Immense clouds of birds lived on the peaks of Meru and Khara, groves grew nearby, evergreen meadows bloomed and tall plants smelled, juicy fruits ripened, and herds of antelopes grazed everywhere.

What could serve as the basis for creating such a picture?

In the strip of adjacent waters there were comparatively productive oases with woody and grassy plants, colonies of waterfowl. With more demanding feed animals. Such productive and resilient ecosystems gave the then man food, raw materials for clothes and other products, fuel, and sheltered from inclement weather. All this according to the Late Glacial «standard» could well be regarded as a blessed life.

From Indo-Iranian myths it is clear that such a life proceeded far in the north, on the shores of the ocean. Over time, the edge of active ice sheets and adjacent water bodies shifted more and more to the centers of glaciations. As a result, the strip of productive glacial ecosystems turned out to be significantly distant from the original mountainous edge of the glaciers — the mythical mountains of Meru and Khara.

In determining the place of origin of the natural plots of Indo-Iranian myths, their hydronyms — the names of rivers — are very valuable. G. Ya. Elizarenkova in the afterword to the translations of the Rigveda notes: «The main river of Vedic geography — Saraswati, which is described as great, full-flowing, fast, flowing out of the heavenly ocean. It’s not possible to precisely identify it with any modern river.»

Orientalists argue that many of the data in Indian and Iranian myths are interpreted unambiguously. Signs of the celestial ocean of Vedic geography are most suitable for subglacial reservoirs. With a long descent of a powerful stream from a high ice sheet, large circuses are usually generated, covered with sandy sediments. A typical circus of this kind is located northwest of the Rybinsk Reservoir, where the glacier-Volga originates. Within this circus, many names of small rivers with sar / sor- ephemente are known: Kumsara, Samosorka, Sora, Chimsora, etc.

On the Caspian lowland stretches a long hollow of the Sarpinsk lakes, along which one sleeve of the water-glacial Volga flowed. So, cap-topoelement is known both at the source and in the delta of the water-glacial Volga.

The river Sarysu adjoins the northern part of the Sarpinsky hollow. This complex hydronym consists of two words: sary — yellow and su (river) (Turk.). Even today in Semirechye «the Steppe Rivers are usually called,» E. M. Murzaev points out, «flowing through clay and loess territories, as a result of which they carry a large amount of suspended material. Their water is really yellowish, muddy. ” Therefore, the prototype of the Vedic Sarastvati may well be the water-glacial Volga.

Cartography Information

Let us now see how the Arctic plots of Indo-Iranian myths are reflected in the monuments of ancient Greek cartography (Bongard-Levin and Grantovsky established this at one time).

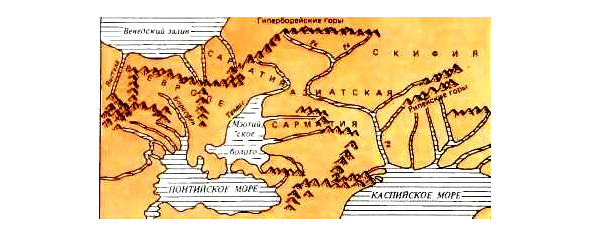

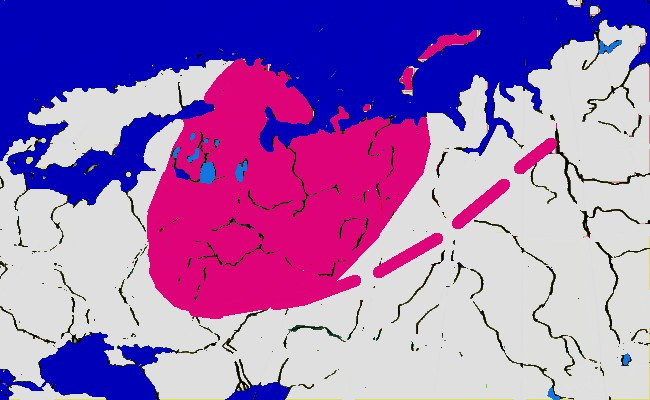

On the map of Ptolemy there is a long mountain range — Hyperborean mountains. This ridge on the Russian Plain exactly coincides with the edge of the Valdai glacier ice sheet.

The hydrographic network of Eastern Europe on the map of Ptolemy resembles the flow diagram of melt glacial waters restored by D. D. Kvasov. The Ptolemaic river Ra and the water-glacial Volga are strikingly similar. The river Ra, according to Ptolemy, originates in the form of two streams near the Hyperborean mountains, apparently in the areas of Belozersk and Valdai. These two streams are combined into one full-flowing channel, most likely, in the vicinity of Kostroma.

Further, the river Ra takes a large river flowing from the Riphean Mountains.

This tributary, undoubtedly, is a section of the Kama from the Ural city of Berezniki to its mouth. In the further course, Ra assumes another left tributary, the route of which coincides approximately with the Urals segment between the cities of Orenburg and Ural and the former northwestern coast of the Caspian Sea during the Khvalyn transgression. On the map of Ptolemy, the Sea of Azov is called the Meotian swamp. It is significant that the swamp is the only sea that was completely lowered in the Valdai glacier due to the lowering of the World Ocean at that time.

The vast expanses of Southeast Europe in Ptolemaic mapping are called Asian Sarmatia. This country coincides with the main loess region of Europe. The areas east of the Vistula, located in the main area of distribution of water-glacial sediments, are called Sarmatia in Europe. Loess and water-glacial deposits differ in brownish-yellow colors. Under the conditions of the Arctic climatic regime, when there was still no dense, continuous vegetation cover, the brownish-yellow color of the parent rocks determined the general color of the landscapes. Perhaps the word «Sarmatia» can be deciphered as «yellow-brown earth (country)»?

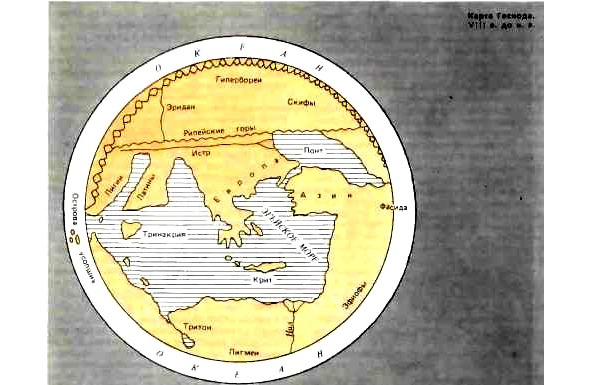

The glacial picture of the Earth is even more distinct on the map of Hesiod (VIII—VII centuries BC). The northern hemisphere on it, mainly Europe, is bordered by some coastal mountains, after which a strip of water extends, the ocean, according to the ancient Greeks, is a great rapid river flowing around the Earth.

During the retreat of ice sheets, hill-shaped ramparts of terminal moraines formed along their edge, along which meltwater rivers flowed. Such a powerful water-glacier stream, with a watershed on the Dnieper and Neman interfluve’s, bordered northern Europe from the British Isles to the Caspian Sea. The space beyond the edge of the ice sheets, then the man was an inaccessible unknown world, like the edge of the earth (Earth). These parallel stripes of the glacial belt of Europe found a clear schematic image on the map of Hesiod.

Late glacial environment is clearly shown by another important detail — the Eridan River. This is the only channel in the northern half of Europe on the Hesiod map that coincides with the Rhine, flows through a mountain range into the ocean (a river flowing around the Earth).

In the beginning, the Late Glacial Rhine really flowed into a full-flowing river on the mountainous strip of regional formations, along which melt water flowed in the western part of the Scandinavian ice sheet.

The ecological and paleogeographic examination of the natural plots of myths and monuments of cartography opens up a multifaceted picture of the late glacial situation. But do all of these data, albeit artistically transformed, have any true foundations, or is it purely fantastic narratives, only by chance, coinciding with past realities? The first seems true.

Such an assumption may raise a number of new questions, for example, the question of the mechanism for transmitting environmental information. Indeed, the era of writing is separated from the early narratives and the first cartographic experiments by about 13 thousand years. It would, of course, be comparatively simple to rely on a hypothesis according to which tales of late glacial realities were transmitted along a continuous line of related offspring. And if this kind of memories of the ice age had to repeatedly pass through the barrier of translation from languages of different families? In this, frankly speaking — unbelievable, case of the accuracy of a primitive man in transmitting geographical characteristics, modern translators, apparently, could envy. The question, however, remains open.

The paleoecological view of distant antiquity extends to some extent the existing ideas about primitive man, clarifies some moments of the resettlement and isolation of ethnic communities, and reveals some realistic basis for mythopoetic creativity. Over time, some of the achievements of paleoecology will probably become useful for a more successful study of the ethnogenetic aspects of the early history of the Indo-Europeans, in particular for the localization of their ancestral home.

Rigveda about the northern ancestral home of the Aryans

In 1903, the work of B. G. Tilak «The Arctic Homeland in the Vedas» was published in Bombay. Its author is an outstanding fighter for the liberation of India from colonial oppression. Devoting his whole life to studying the culture of his native people, he long and carefully studied ancient legends, legends, sacred hymns, born in the depths of millennia and brought to the territory of Hindustan by the distant ancestors of the Indians from their ancient ancestral home.

Summing up the phenomena that were described in the holy books of the Vedas in the ancient Indian epic Mahabhara, B. G. Tilak came to the conclusion that the ancestral home of the ancestors of the Indo-Iranians (or as they called themselves — «Aryans») was in northern Europe, somewhere near the Arctic Circle.

E. Jelachich, who published the book «The Far North as the Homeland of Humanity» in the 1910s, also leads to the same conclusions. The time of occurrence of the most ancient parts of the Veda dates back to 4—5 thousand BC, i.e. to the period when, according to some researchers, «Indo-Iranians separated from the Slavs as a community.» Linguists came to the conclusion that «the ancient Aryan languages with Slavic have a much more painful number of similarities than with any other language of the Indo-European family.» Created in ancient times by the common ancestors of the Slavic and Indo-Iranian peoples, the Vedas hymns, along with the ancient Iranian Avesta, are considered one of the oldest monuments of human thought.

Numerous geographical and astronomical evidence of the Rigveda, the oldest part of the Vedas, speak of the knowledge by the aryans of the circumpolar regions of Eastern Europe. The North Star is described as the axis of the world around which the entire starry sky moves and above all the Ursa Major. Only in the polar polar latitudes during the polar night can you see how the stars describe their diurnal circles near the motionless North Star. In the hymns of the Rigveda and Avesta it is said that in the homeland of the Aryans, the night lasts at least 100 days a year, that «the dawns do not brighten until the end» for thirty days, that with the end of the night and the arrival of the day the ice-bound rivers are released. The ancient Indian epic describes the appearance of the Supreme God to the sage Narada in the form of flashes of the Polar Lights. (It is interesting that the highest peak of the Subpolar Urals is called Narada).

The Rig Veda describes, in connection with the homeland of the Aryans, an ongoing day that lasts six months. One of the main geographical landmarks of the land of the Aryans is the sacred mountains, which are described as stretching from west to east and dividing the rivers into the currents flowing north into the White Sea and south into the warm sea. On the map of Ptolemy (1st century), the sacred river «Avesta» Ra or Rga (i.e. Volga) originates from these mountains. The ancient holy Iranian river flowing north was called Ardvi Sura, which means the mighty double river. These mountains, sung in ancient Aryan anthems, stretching from west to east and dividing rivers into northern and southern, are reliably identified at present with the mountain range of the Subpolar Urals, Timan Ridge and Northern Uvals. The Northern Uvals served as the main watershed of the rivers of the south and north of Eastern Europe during the Carboniferous period, when the ancient sea splashed in the place of the Urals.

The description of the northern ancestral home of the Aryans as a flowering region corresponds to historical reality, because according to the data of modern paleoclimatology in 4—3 thousand BC the temperature rise in the forest and tundra zones coincided with their drop south of 50—55 gr. N. Paleobotanists note that in 4 thousand BC in the north of Eastern Europe, July temperatures were higher than currently at 5° C. Such a greatest warming was characteristic of the northern part of the continent (north of 55—60° N, i.e., beyond the Northern Uvals, on the White Sea coast), to the south it decreased and approximately at a latitude of 50 gr. N temperatures were close to modern. At latitudes 57—59° N the frost-free period was 30–40 days longer than the modern one.

It should be noted that, as academician L. S. Berg noted in 1947, «paradoxically at first glance, the yield of bread in the taiga subzone (as well as in the mixed forest subzone, i.e., in general in the non-chernozem zone) is much higher than in the steppes.» According to the data of 1901—1910, the excess of average yields in the Non-Chernozem region over the chernozem provinces was: oats — 51%, barley — 60%, spring wheat — 33%, winter — 42%. According to the paleoclimatic map, already in the Mesolithic, the territory of the modern Vologda region and a significant part of the Arkhangelsk region were in the subzone of broad-leaved forests. Paleoclimatologists believe that 8—4.5 thousand years ago, «a strip of broad-leaved forests in the west of the Russian Plain reached 1200—1300 km. in the meridional direction, broad-leaved formations in the composition of broad-leaved — coniferous forests spread over 500—600 km. north of their current situation.»

In the Russian North, to this day you can meet such hydronyms as Usa, Uda, Sheaf, Sindosh, Indola, Indosar, Strig, Svaga, Svatka, Varna, Pan, Thor, Arza, Prupt. Hvarsenga, etc., which are explained using the ancient language of the Aryans — Sanskrit. And it was precisely in the places where these ancient names of rivers and lakes were preserved that the tradition of ancient geometric ornamental complexes, the sources of which can be found in the ancient cultures of Eastern Europe of 6—2 thousand, was persistently preserved in the weaving and lace of Russian peasant women until the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th century. BC. And above all, these are those ornamental complexes, often very complex and difficult to do, which were a peculiar hallmark of Aryan antiquity.

Plants of the Indo-European Motherland

(Based on materials by V. A. Safronov, T. V. Gamkrelidze, Vyach. Vs. Ivanova)

The problem of localization of the ancestral home of Indo-European peoples has been facing science for a long time. As early as the mid-18th century, the linguistic kinship of European peoples was noted, and in 1767 the Jesuit monk Kerdu noted the proximity of a number of European languages to Sanskrit — the language of the sacred texts of the Ancient India of the Vedas.

Friedrich von Schlegel, the first to express the idea of a single ancestral home of all Indo-Europeans, placed this ancestral home on the territory of Hindustan.

«The decisive factor for the emergence of Indo-European studies was the discovery of Sanskrit, acquaintance with the first texts on it, and the enthusiasm that began with ancient Indian culture, the most striking reflection of which was the book of F. von Schlegel «On the language and wisdom of Indians» (1808), writes V.N. Toporov.

However, the fallacy of this assumption was soon proved, since before the arrival of the Aryan (Indo-European) tribes, India was inhabited by representatives of another language family and another racial type — black Dravids.

Assumed at different times as the ancestral home of the Indo-Europeans (and these are today the peoples of 10 language groups: Indian, Iranian, Slavic, Baltic, German, Celtic, Romance, Albanian, Armenian and modern Greek): India, the slopes of the Himalayas, Central Asia, Asian steppes, Mesopotamia, Near and Middle East, Armenian Highlands, territories from Western France to the Urals between 60° and 45° N, territory from the Rhine to the Don, Black Sea-Caspian steppes, steppes from the Rhine to Hindu Kush, areas between the Mediterranean and Altai, in Western Europe — currently, for one reason or another, most researchers rejected.

Among the hypotheses formulated in recent years, I would like to dwell on two in more detail: V.A. Safronov, who proposed in his monograph Indo-European Ancestral Homes the concept of the three ancestral homelands of the Indo-Europeans — in Asia Minor, the Balkans and Central Europe (Western Slovakia), and T.V. Gamkrelidze and V.V. Ivanova, who own the idea of the Near Asian (more precisely, located on the territory of the Armenian Highlands and the adjacent areas of Western Asia), the ancestral home of the Indo-Europeans, detailed and argued by them in the fundamental two-volume «Indo-European language and Indo-Europeans».

1

V. A. Safronov emphasizes that on the basis of the Early Indo-European (hereinafter RIE) vocabulary, it can be concluded that «the Early Indo-European society lived in cold places, maybe in the foothills, in which there were no large rivers, but small rivers, streams, springs; rivers, despite the rapid flow, were not an obstacle; crossed through them in boats. In winter, these rivers froze, and in the spring they overflowed. There were swamps… The climate of the ancestral homeland was probably sharply continental with severe and cold winters, when the rivers froze, strong winds blew; in a stormy spring with thunderstorms, heavy snowmelt, river spills, hot, dry summers, when the grass was dry, there was not enough water. The early Indo-Europeans had early phases of agriculture and cattle breeding, although hunting, gathering and fishing did not lose their significance.

Among the tamed animals are a bull, a cow, a sheep, a goat, a pig, a horse and a dog that guarded the herds.

He notes that: «Riding was practiced by the early Indo-Europeans: what animals were circled is not clear, but the goals are obvious: taming.» Agriculture was represented by a hoe and kidney-fire form, the processing of agricultural products was carried out by grinding grain.

The early Indo-European tribes lived settled; they had different types of stone and flint tools, knives, scrapers, axes, adzes, etc. They exchanged and traded. In the early Indo-European community there was a difference in childbirth, taking into account the degree of kinship, and juxtaposition of friends and foes. The role of women was very high. Particular attention was paid to the «progeny generation process», which was expressed in a number of root words that passed into the RIE language from the boreal parent language. In the RIA society, a pair family stood out, management was carried out by leaders, there was a defensive organization.

There was a cult of fertility associated with zoomorphic cults; there was a developed funeral rite.

V. A. Safronov concludes that the ancestral home of the early Indo-Europeans was in Asia Minor. He notes that such an assumption is the only possible, because Central Europe, including the Carpathian basin, was occupied by a glacier.

However, paleoclimatology data indicate something else. At the time in question, that is, during the final stage of the Valdai glaciation, the chronological framework of which was established from 11,000 to 10,500 years ago, i.e. 9 thousand BC, the nature of the vegetation cover of Europe, although it differed from modern, in Central Europe, Arctic tundra with birch-spruce woodlands, low-mountain tundra and alpine meadows, rather than a glacier, were common. Sparse forests with birch-pine stands occupied most of Central Europe, and on the Great Central Danube Lowland and in the southern part of the Russian Plain, vegetation of the steppe type prevailed.

Paleogeographers note that in southern Europe, the influence of ice cover was almost not felt, especially in the Balkans and Asia Minor, where the influence of the glacier was not felt at all. The time is 8—7 thousand BC, to which the culture of Asia Minor Chatal Guyuk belongs, connected by V. A. Safonov with the early Indo-Europeans, marked by the warming of the Holocene. Already 9780 years ago, elms appear in the Yaroslavl region, 9400 years ago in the Tver region and 7790 years ago oaks in the Leningrad region. Moreover, the presence of a cold climate in Asia Minor is unlikely. Here I would like to refer to the conclusions of L. S. Berg and G.N. Lisitsina, made at different times, but, nevertheless, not refuting each other.

So L.S. Berg, in his 1947 work, Climate and Life, emphasized that the climate of the Sinai Peninsula has not changed over the past 7000 years and that here, and in Egypt, «if there had been a change, it would be more likely to increase rather than decrease atmospheric precipitation». He noted that: «Blankengorn believed that in Egypt, Syria and Palestine the climate in general has remained constant and similar to the current one since the end of the plural period; the end of the latter, Blanquengorn refers to the beginning of the interglacial era ” (130—70 thousand years ago).

In a 1921 paper, Blankengorn writes that «From the Riesz-Wurm interglacial (Mousterian of Western Europe) to modernity (S. Zh. in these territories), dry desert, and in the north, a semi-desert climate similar to the modern one, interrupted by a short wet time corresponding to the Wurm glaciation.»

G.N. Lisitsina in 1970 comes to similar conclusions and writes: «The climate of the arid zone in 10—7 millennia BC not much different from the modern one.»

We have no reason to believe that the climate of western Asia Minor, where daphne, cherry, barberry, maquis, Calabrian pine, oak, hawthorn, hop-hornbeam, ash, white and prickly astragalus grow, live such animals as mongoose, jackal, porcupine, mouflon, wild donkey, hyena, bats and locusts, and tender cover, as a rule, does not form, in 8—7 thousand BC so much different from the modern one so that it could be similar to the harsh ancestral home of the early Indo-Europeans, which is being reconstructed based on their vocabulary.

In addition, V.A. Safonov writes: «The deep kinship of the Boreal with the Turkic and Uralic languages, according to N.D. Andreev, allows you to localize the boreal community in the forest zone from the Rhine to Altai. From this it also follows that from all areas where RIE carriers could have gone, Anatolia seems to be the only possible one: narrow straits did not serve as an obstacle, since the early Indo-Europeans knew the means of crossing (the „boat“ was recorded in the language of the early Indo-Europeans).»

As for the role of the Early Indo-Europeans in the world historical process, it is difficult to disagree with the main conclusions of V.A. Safronov made him in the final part of his work. Indeed: «In solving the problem of the Indo-European ancestral homeland, which has been exciting for two centuries by scientists from many professions and various countries of the world, they rightly see the origins of the history and spiritual culture of the peoples of most of Europe, Australia, and America. «Just as their descendants, Indo-Europeans of the new time, dug the New World, so the Indo-Europeans of the Ancient World revealed to humanity the knowledge of the integrity of the earthly home, the unity of our planet… These discoveries would remain nameless if the echoes of the great wanderings could not be kept in Indo-European literature, separated from us and from these events for thousands of years… Indo-European travels became possible thanks to the invention of wheeled transport (4 thousand BC) among Indo-Europeans. ” And we add, due to the domestication of a wild horse in the southern Russian steppes already on the border 7—6 millennia BC As noted by N.N. Cherednichenko: «At present, the spread of a draft horse from the Eurasian steppes is no longer in doubt… the process of taming a horse is carried out on the distant plains of the Eurasian steppe region… Thus, at present, we can only talk about ways of penetration of the Indo-European horse breeding tribes of Eurasia on East and in the Mediterranean… Eurasia, therefore, was the territory from where the chariots were brought by Indo-European tribes to various regions of the Old World, which greatly affected oliticheskoy life of the Ancient East.»

V.A. Safronov notes that «The period of the general development of the Indo-European peoples, the pre-Indo-European period, was reflected in the amazing convergence of the great literatures of antiquity, such as the Avesta, Vedas, Mahabharata, Ramayana, Iliad, Odyssey, in the epics of the Scandinavians and Germans, Ossetians, legends and tales of the Slavic peoples. These reflections of the most complex motifs and plots of common Indo-European history in ancient literature and folklore, separated by millennia, are fascinating and await their interpretation. However, the emergence of this literature became possible only thanks to the creation by the Indo-Europeans of the metric of poetry and the art of poetic speech, which is the oldest in the world and dates back no later than 4,000 BC… By creating our own system of knowledge about the universe, which opened the way for civilization to humanity, the Indo-Europeans became the creators of the most ancient world civilization, which is 1000 years older than the civilizations of the Nile Valley and Mesopotamia. There is a paradox: linguists, having recreated according to linguistics the face of the pre-Indo-European culture, by all signs of the corresponding civilization, and determined it to be the oldest in the series of known civilizations (5—4 millennia BC), could not cross the rubicon of historical stereotypes that «light always comes from the East», and limited themselves to the search for the equivalent of such a culture in the areas of the Ancient East (Gamkrelidze, Ivanov, 1984), leaving Europe aside as the» periphery of Middle Eastern civilizations».

The civilization of the pra-Indo-Europeans turned out to be so high, stable and flexible that it survived and survived despite the global cataclysms.

V.A. Safronov emphasizes that «It was the late Indo-European civilization that gave the world a great invention — wheel and wheeled transport, that it was the Indo-Europeans who created the nomadic economy», which allowed them to go through the vast expanses of the Eurasian steppes, to reach China and India. "And summing up, he writes: «We believe that the guarantee of stability of the Indo-European culture was created by the Indo-Europeans. It is expressed in the model of the existence of culture as an open system with the inclusion of innovations that do not offend the foundations of its structure.»

As a form of coexistence with the world, the Indo-Europeans proposed a model that was maintained in all historical times — the removal of factorial colonies into a foreign-language and foreign culture environment and bringing them to the level of development of the metropolis. The combination of openness with tradition and innovation, the formula of which was found for each historical period of the development of Indo-European culture, ensured the preservation of Indo-European and universal values. ” We allowed ourselves such a long quotation, since it is difficult to more clearly, compactly and comprehensively determine the importance of the pre-Indo-European and early Indo-European culture for the destinies of mankind than this was done in the work of V.A. Safronova «Indo-European ancestral home.»

2

The next fundamental work devoted to the ancestral home of the Indo-Europeans, the main provisions of which I would like to dwell on, is the work of T.V. Gamkrelidze and Vyach. Sun Ivanov’s «Indo-European language and Indo-Europeans», where the idea of a common Indo-European ancestral homeland on the territory of the Armenian Highlands and the adjacent areas of Western Asia, from where part of the Indo-European tribes then advanced into the Black Sea-Caspian steppes, develops and is thoroughly argued.

Paying tribute to the very high level of this encyclopedic work, which collected and analyzed a huge number of linguistic, historical facts, data from archeology and other related sciences, I would like to note that a number of provisions postulated by T.V. Gamkrelidze and Vyach. Sun Ivanov, causes very serious doubts.

So V.A. Safronov notes that: «The linguistic facts cited by Gamkrelidze and Ivanov in favor of localizing the Indo-European ancestral homeland on the territory of the Armenian Highlands can receive other explanations. The absence of hydronymia in this area can only indicate against the localization of the Indo-European ancestral home. The environmental data presented in the parsed work contradict this localization even more. Almost half of the animals, trees and plants listed in the list of flora and fauna listed by Gamkrelidze and Ivanov are reconstructed in the Common Indo-European (aspen, hornbeam, yew, linden, heather, beaver, lynx, black grouse, salmon, elephant, and monkey) crab).»

It is on these environmental data cited in the work of T.V. Gamkrelidze and V.V. Ivanova, I would like to dwell in more detail. The authors of the «Indo-European language and Indo-Europeans», in confirmation of their concept, indicate the oldest names of trees recorded in the ancient Indo-European parent language.

These are birch, oak, beech, hornbeam, ash, aspen, poplar, yew, willow, branches, spruce, pine, fir, alder, walnut, apple, cherry, and dogwood. And in connection with this, the following is affirmed:

Birch

«Birch species are currently found throughout the temperate (northern) zone of Eurasia, as well as in the mountainous regions of the more southern zones, where it grows to an altitude of about 1,500 m (in particular in the Caucasus, on the spurs of the Himalayas and in the mountainous regions of Southern Europe).

In the subboreal period (about 3300—400 BC), birch was also distributed in the more southern belt… The presence of a common word for birch in the Indo-European suggests familiarity with the ancient Indo-European tribes, which was possible either in the zone temperate climate (in Europe at latitudes from the north of Spain to the north of the Balkans and further east to the lower reaches of the Volga), or in mountainous regions of the more southern range of the Near East.»

However, Academician L.S. Berg in 1947 emphasized that in the northern part of Eastern Europe 13—12 thousand years ago there were forests of birch and pine.

In the warming that began 11—10 thousand years ago, the absolute maximum of birch was noted.

These conclusions are also confirmed by materials prepared by Russian paleoclimatologists for the XII Congress of INKVA (in Canada in 1987), which indicate that in the Vychegda and Upper Pechora river basins in layers 45210 +1430 years ago pine and birch in combination with cereal forbs prevailed. In the forests, pine made up 44%, birch up to 24%, spruce — 35 to 15%.

In the north of the Pechersk lowland in the postglacial period, i.e. 10—9 thousand years ago, «woody vegetation developed territories» and these were forests of birch, spruce and pine. Data on Belarusian Polesie indicate that 12,860 ± 110 years ago (i.e., at the beginning of 11 thousand BC), pine-spruce forests and associations of pine-birch forests with an admixture of broad-leaved: oak, elm and linden trees.

Samples of peat from the marshes of the Yaroslavl, Leningrad, Novgorod and Tver regions, performed in the laboratory of V.I.Vernadsky Institute, confirm that the peak of birch distribution dates back to about 9800 years ago, 7700 years ago — the absolute dominance of birch. L.S. Berg wrote: «A study of the history of vegetation in the post-glacial time, carried out by analyzing pollen from peat, showed that in the central part of the Union, immediately after the retreat of the glacier, first there were a large number of birch and willow, and then called subarctic time, prevalence passed to spruce and birch; in the next boreal era, birch and pine began to dominate.»

I must say that birch is one of the most important forest-forming species in Eastern Europe since the time of the Mikulinsky interglacial (130—70 thousand years ago) and up to the present day.

The authors of the «Paleogeography of Europe for the Last Hundred Thousand Years» note that: «Tracing the Holocene history of birch, one might think that primary birch forests are much wider in modern forests of the European part of the USSR than is usually assumed.»

At the same time, nothing testifies to the wide distribution of birch in antiquity in the Near East and on the Armenian Highlands. L.S. Berg emphasized that: «The climatic situation of Palestine at the northern border of palm culture and at the southern limit of grape cultivation has not changed since biblical times. As for the Armenian Highlands, at present it is a combination of folded-block ridges and tectonic depressions, often occupied by lakes — closed saline (Van, Urmia), and less commonly — flowing fresh (Sevan). Semi-desert and even desert landscapes are characteristic of the deepest depressions. There is a dry feather grass and steppes, «in some places in the middle course (between 1000 and 2300 m) there are dry rare forests of deciduous oaks, pine and juniper.»

In the Iranian highlands, in the mountains of Zagros (on the western slopes and in the wetter northern part, between 1000 and 1800 m.), Park oak forests with elm and maple are common, and wild mulberries, poplar, oak, and figs are found in the valleys. Due to the fact that the period from the middle of 1 thousand BC hitherto defined by climatologists as the period of cooling and moistening with respect to the climatic optimum of the Holocene (4—3 thousand BC) and the previous time (7—5 thousand BC), there is no reason to suppose on these the southern territories have a much more humid and colder climate in 7—3 thousand BC, i.e. the time in question in the work of T.V. Gamkrelidze and V.V. Ivanov.

Further, the authors of the «Indo-European language and Indo-Europeans» write: «The main economic value of birch is determined by the fact that it served in antiquity (and still serves in separate traditions) as material for the manufacture of a wide variety of items from shoes, dishes, baskets, to writing material in certain cultures, in particular among the Eastern Slavs and in India until the 16th century.»

A.A. Kachalov points out that: «the inhabitants of the Himalayas use birch bark useful for this purpose in our time.»

«The connection of trees — birch, beech, hornbeam with the terminology of writing indicates the technique of writing and the manufacture of materials for writing in ancient Indo-European cultures. The emergence of writing and writing is based in these cultures on the use of wood and wood material, on which signs or nicks were applied using special wooden sticks. This writing technique, characteristic of a number of early Indo-European cultures, obviously reflects a typologically more archaic degree of writing development than carving signs on stone, or applying them to clay tablets, or to specially processed animal skin.»

I must say that it is difficult to imagine that a simpler, more affordable, maneuverable and less laborious letter on birch bark was more primitive than an uncomfortable, bulky letter on clay tablets or carving inscriptions on stone. Indeed, if there were both clay and birch bark from the early Indo-Europeans, they would hardly have switched from writing on birch bark to using clay tablets for business correspondence or for business records.

In addition, the question arises why birch bark, as a material for writing, was preserved precisely in the East Slavic and Indian ethnic range. If you follow the findings of T.V. Gamkrelidze and V.V. Ivanova, the Slavic and Indo-Iranian branches of the Indo-European community dispersed even on the territory of their supposed common ancestral home in Asia Minor (where there are practically no birches).

The Pre-Slavs left for Eastern Europe, and the Indo-Iranians moved to Iran (where birch is not common) and Hindustan, where only the Himalayas grows at a height of 2,500–4,300 m, the «useful birch», the «Jacquem birch» and, finally, the birch of the Akuminat section — a tree 20—30 m high with very large leaves. But these trees are not widespread in India and are considered endemic to a very narrow range. But in the Indian tradition, birch bark is not just writing material, but sacred material: on birch bark (and only on birch bark) a record was made of marriage in the higher castes and without this record on birch bark, marriage was not considered valid. This situation could not develop in areas where birch is almost not widespread.

Birch bark could become material only where birch has been one of the main forest-forming species for many millennia — in the forest strip of Eastern Europe. It makes sense to pay attention to the following circumstance. T.V. Gamkrelidze and V.V. Ivanov emphasize that birch bark was used for writing in the most ancient Indo-European cultures and was preserved in this quality among the Eastern Slavs and in India until the 16th century.

But the ancestors of the East Slavic peoples and the Aryan peoples of NorthWest India dispersed no later than 2 thousand BC and, nevertheless, birch bark, as a material for writing, was preserved precisely among the Eastern Slavs and Indians. It follows from this that birch bark was still on their common ancestral home as a material for writing.

Then the conclusion is also natural that long before 2 thousand BC the ancestors of the eastern Slavs had writing and the predecessors of the Novgorod and Pskov birch bark letters were older than them for many millennia.

It is also interesting that in the North Russian tradition birch bark and in the 19th century (as in India) was precisely sacred material for writing. This is evidenced by the story of an outstanding ethnographer of the 19th century. S.V.

Maximov wrote about the Old Believers birch-bark book decorated with miniatures, which the old Pomor man from Arkhangelsk did not want to sell for any money. S.V. Maksimov notes that this book, «written by half-mouth» on birch bark, «finely and successfully stripped, and assembled, sewn into quarters… The written was disassembled as conveniently as the written on paper, the letters did not spread, but they stood straight, one beside the other: another paper makes letters worse… the book was somehow bound in a homegrown way into plain, birch bark boards.»

«To write such a book: sticky soot is made from a burnt birch peel, which, when diluted in water, gives decent ink, at least those that can leave a very noticeable mark on their own if they are wiped off on the top layer. Eagles and wild geese, which are many on the tundra and which are difficult to fly away from the well-aimed shot of the usual hunters, give good feathers. And here’s the henchman, always comfortably peeling over the layers of birch bark, which can be turned into pages and on which you can write soon and, perhaps, clearly, «writes S.V. Maximov.

The sacred nature of birch bark, as a material for writing, is evidenced by the customs preserved in the Russian North almost to the present day. So A.A.

Veselovsky in his «Essays on the History of the Life and Work of Peasants of the Vologda Province» describes a rite of «unsubscribing», in which the healer «whispers, writes a note and puts it into the wind and makes the patient easier.»

They write a petition on birch bark, and the father-wind takes it away. From the same series, it is customary to write conspiracies and letters to the devil — «bondage» — on birch bark, and the text is not written (in the literal sense of the word), but is applied by soot in the form of erratic strokes, oblique crosses, curving lines, etc.

All this testifies to the now anciently forgotten, supplanted Cyrillic alphabet, the ancient Slavic writing system. Perhaps her relics are the mysterious signs on the manure of the North Russian icons and the so-called «ornaments» painted by Dionysius on the arch of the portal of the Cathedral of the Nativity of the Virgin in the village of Ferapontovo.

Oak

T.V. Gamkrelidze and V.V. Ivanov believe that the early Indo-Europeans could get to know this tree only in the southern regions of the Mediterranean (including the Balkans and the northern part of the Middle East), because «Oak forests are uncharacteristic of the northern regions of Europe, where they spread only from 4—3 thousand BC.»

However, it is now known that oak forests were widespread in northern Europe (and Eastern Europe in particular) during the Mikulinsky interglacial period (130—70 thousand years ago). During the peak of the Valdai glaciation (20—18 thousand years ago), in a number of regions of the Russian plain there were forests with the participation of broad-leaved species such as oak and elm. At the beginning of 11 thousand BC (12860 +110 years ago) in the Belarusian Polesie there were widespread associations of pine-birch forests with an admixture of broad-leaved: oak, elm and linden. During the Mesolithic, a significant part of the territory of modern Vologda and Arkhangelsk regions was covered with deciduous forests, which include oak forests.

S.V. Oshibkina notes that at the Mesolithic site Pogostishche in the East Prionegie (7 thousand BC) the forest consisted of birch, pine, a small amount of spruce and mixed oak forest. L.S. Berg noted that as early as 9—8 thousand BC «In the Neva basin separate pollen grains of broad-leaved species and hazel trees appear», and in 5–4 thousand BC here noted «a large, distribution of oak forests with linden, elm and hazel.»

Conclusions L.S. Berg is confirmed by data obtained by domestic geochemists in 1965. It is noted that starting from the turn of 7—6 thousand BC «The pollen spectra are characterized by a high pollen content of broad-leaved species… Here are the climax points of the curves of oak, elm, hazel and alder.» We emphasize that the culmination of the distribution of oak in the Tver region dates back to 6945 years ago (i.e., the beginning of 5 thousand BC), and in the Leningrad region — to 7790 years ago (i.e., the beginning of 6 thousand BC. e.). In addition, in the Neolithic and Bronze Age, it was in Eastern Europe that the largest zone of oak forests in Europe was located.

Thus, the thesis about the presence of oak forests in ancient Indo-European time only in the Mediterranean, mountainous areas of Mesopotamia and adjacent areas is completely groundless.

Beech

The authors of the «Indo-European language and Indo-Europeans» note that the name «beech» is not in the Indo-Iranian languages. This is more than strange if we accept the hypothesis. V.V. Ivanov and T.V. Gamkrelidze on the Near-Asian ancestral home of the Indo-Europeans.After all, this tree was in ancient times one of the main forest-forming in the Transcaucasia and Western Asia. The fact that the ancient Indo-European name of beech has not been preserved in Indian languages can still be explained — there is no beech on the territory of Hindustan.

But how could the Iranians lose this ancient Indo-European name if the beech is the main forest-forming not only in the Near East and the Armenian Highlands (the supposed oldest ancestral home), but also in the Iranian Highlands — the new homeland of the Iranians (according to T.V. Gamkrelidze and V. V. Ivanov)?

After all, G.I. Tanfilyev (the chief botanist of the Imperial Botanical Garden, an outstanding phytogeographer and connoisseur of the flora of Russia), describing the vegetation of the Caucasus in 1902, noted that «the forests here consist mostly of beech mixed with chestnut and oak.» Currently, in the Caucasus, beech occupies almost half of the total area covered by forests. It is widespread on the northern slopes of the Caucasus, in Transcaucasia it is characterized by almost continuous distribution, and only in the upper reaches of individual rivers gives way to conifers. It runs along the main ridge from the Black Sea coast to the eastern border of forests (Shemakha), along the Lesser Caucasus to the east to the Terter River, and in the east it is again found in Talysh, leaving the foothills of Elburz to Iran.

The same picture was observed in antiquity: pollen analysis of samples from the bottom of the Black Sea, dating from the beginning to the middle of 6 thousand BC, when there was a rapid filling of the freshwater Black Sea with salt water from the Bosphorus, indicate the presence of forests from hornbeam, beech, oak and elm! Apparently, the picture has not changed to this day. But then it is absolutely inexplicable how the ancient Iranian tribes, who came from their supposed ancestral homeland with its beech forests to the territory, where beech forests also prevailed and still prevail, the ancient Indo-European name of this tree was completely lost. Probably, such a situation could only develop if the ancient Iranians came to the territory of the Iranian Highlands from areas where the beech does not grow. And here it is appropriate to recall that, as T.V. Gamkrelidze and V.

V. Ivanov: «to the north-east from the Black Sea coast to the lower reaches of the Volga throughout the entire postglacial period» there is no beech.

Hornbeam

And with this tree, whose ancient Indo-European name is in many Indo-European languages, but not in the Indo-Iranian, a situation similar to beech has developed. The hornbeam grows in the Near East, making up a significant part in the forests on the western shore of the Caspian Sea. He dominates with the oak in Karabakh. In the Caucasus, in Southern and Eastern Europe (pure hornbeam forests are known only east of the Vistula and in the upper Bug), in Asia Minor and Iran, the eastern hornbeam or hornbeam growing in the lower, less often middle belt of mountains to a height of 1200 m is common. Like beech, throughout the postglacial period to the north-east of the Black Sea, the hornbeam is absent. And (one can see a certain regularity in this) the name of the hornbeam is absent in the Indo-Iranian languages.

Yew

This ancient Indo-European name also does not exist in the Indo-Iranian languages. «Yew is distributed in Europe from Scandinavia to the mouth of the Danube, its eastern border roughly coincides with the border of beech… Yew in historical times is not found in Eastern Europe and the Northern Black Sea region.»

But «yew is especially widespread in the more southern regions of the Caucasus (starting from the North Caucasus), in Asia Minor and some parts of the Balkans,» write T.V. Gamkrelidze and V.V. Ivanov.

The situation repeats itself, similar to the situation with beech and hornbeam.

Yew is growing in the alleged Near-Asian ancestral homeland, is also widespread in the new Iranian homeland, and there is no Indo-European name for this tree in the Indo-Iranian languages, just as it was not in historical time in Eastern Europe and the Northern Black Sea region.

Fir

«Fir in its various forms is known from the Middle and Late Atlantic period (7—4 thousand BC) in Transcaucasia and Western Asia, as well as in the lower Volga, in Eastern Europe, in the Pripyat — Desna basin. Later, fir is pushed aside by some other types of trees, preserved mainly in the mountainous regions of Europe, the Caucasus, Western Asia and Eastern Europe, «T.V. Gamkrelidze and V.V. Ivanov.

But I would like to draw attention to the fact that even during the peak of the Valdai glaciation, when, unlike Western Europe, «within the Russian Plain, forests occupied a large area in the form of a wide strip crossing it in the direction from the south-west to north-east», they were represented mainly by birch-pine and spruce-fir forests.

At the same time: «With regard to the non-moral and subtropical types of shrub forests, the following should be noted: the fact that these types were preserved in southern Europe during the glaciation in Valdai clearly indicates the result of flococenogenetic analysis of modern vegetation of the Mediterranean countries.»

How in such a situation, when the climate of Asia Minor has not changed from the time of the Valdai glaciation to the present day, fir could be pushed to the mountainous regions of Europe, the Caucasus and, most importantly, Asia Minor, where it is not currently located?

According to modern vegetation maps in the Old World, the range of the genus fir is it is the northeast of the European part of Russia, Siberia, China (northwest), slightly in the Caucasus and the Western Mediterranean.

G.I. Tanfilyev noted that: «In the European taiga they come from Siberian species, except for larch, still fir and cedar. Of these, cedar grows on this side of the Urals in small groups and individual trees among forests and other species, while larch and fir in places form even forests in places. ” Currently, fir in our country occupies 12 million hectares. Thus, there is no certainty that fir grew in antiquity in Asia Minor, but the fact that it had and has an extensive range in northeastern Europe and in Siberia is a fact.

Pine

V.V. Ivanov and T.V. Gamkrelidze write that pine and its varieties from antiquity are represented in the mountainous regions of the Caucasus and the Carpathians, as well as in the Black Sea region. But it should be noted that in ancient times, pine was spread by no means only in these territories. So, at the peak of the Valdai glaciation in the Oka basin, spruce-pine forests of the north-taiga type were noisy, in the middle reaches of the Desna forests with spruce and Siberian cedar pine were locally distributed.

According to paleogeography in the ancient Holocene (11 thousand years ago), spruce, pine and alder were present in the forests of the Vologda Oblast. A similar situation was in other areas of the central part and the north of Eastern Europe. In general, conifers began to play a significant role in the vegetation cover of Eurasia since the Triassic period, which began about 240 million years ago.

«Among modern conifers, the most ancient families are Araucariaceae, Podocarpaceae, and especially pine… plant residues (including pollen grains), more or less confidently related to the pine genus, are known from Jurassic deposits.»

Currently, forests with a predominance of pine are most pronounced in the northern regions of Eurasia and North America. Pine forests in our country occupy an area of 108 million hectares. The range of the genus pine is all of Europe, Siberia, the Himalayas, the Pamirs, China, Japan, and Asia Minor. In Western Asia there is no pine!

Pine forests are not as significant as T.V. Gamkrelidze and V.V. Ivanov, and in the Caucasus. So G.I. Tanfilyov, describing the forests of the Western Transcaucasia, notes that: «The coastal pine tree, which is found only at the very sea, is very typical of the coastal pine, a tall tree growing in small groups between Novorossiysk and Cape Pitsunda, and only at this last point it forms a large forest.»

He notes that «in the forests on Talash there are no conifers at all except yew and juniper», and «in the East Caucasus only pine and juniper are found from coniferous species, of which pine, however, goes only to the meridian of Elisavetpol.»

Spruce

The authors of the «Indo-European language and Indo-Europeans» argue that: «In ancient times, spruce was represented only in the highlands, in particular in the Caucasus and in the mountainous regions of Central and Southern Europe.»

However, L.S. Berg believed that: 11—10 thousand years ago, spruce forests prevailed in the north and in the center of Eastern Europe; 9—8 thousand years ago, the amount of spruce fell slightly; 7—6 thousand years ago, in a temperate, warm and humid climate, the secondary distribution of spruce began; and in 1 millennium BC in colder and wetter conditions, spruce begins to penetrate into oak forests.

The botanical data indicate that at present «most species and individuals of spruce are kept in an area whose southern border does not extend beyond 35° N, and the vast majority of spruce stands is located much north».

And, moreover, even during the maximum of the Valdai glaciation (18–20 thousand years ago), 55 N up to 63° N meadow steppes with birch and spruce forests.

As for the Caucasus, spruce is distributed here «mainly in the west of the Greater Caucasus, both on its northern slopes and in the Caucasus, reaching almost Tbilisi in the East. The southern and southeastern border of the eastern spruce lies in Anatolia. ” Thus, the range of the spruce genus is the north of Eurasia, the Himalayas, China and a few Balkans, Asia Minor and the Caucasus, i.e. the thesis that: «In antiquity, spruce was represented only in high mountain regions, in particular in the Caucasus and in the mountainous regions of Central and Southern Europe» seems unconvincing.

Dogwood

T.V. Gamkrelidze and V.V. Ivanov write that: «Dogwood is prevalent mainly in the relatively more southern regions of Europe, the Caucasus and Western Asia.»

But at present, 15 species of wild dogwood are growing in our country, among them: holly dogwood, reaching in the European part Arkhangelsk, where it bears fruit as well as in Crimea; Cotoneaster, common in Crimea, the Caucasus and Western Asia, also bearing fruit to the latitude of Arkhangelsk; cotoneaster whole or ordinary, growing in the Baltic states, Western Belarus, the Caucasus, Zap.

Ukraine, in the Crimea and Central Asia, and also reaching Arkhangelsk; black-fruited cotoneaster, common in Eurasia from Central Europe to China, and from Lapland to the Caucasus and Central Asia, growing everywhere except for the tundra and uninhabited deserts.

But, at that time, about which T.V. Gamkrelidze and V.V. Ivanov is said to be of common Indo-European (i.e. 5—4 thousand BC), there were practically no tundra in Eastern Europe. In addition, dogwood varieties are widely distributed under the general name derain, about 50 species of which grow in temperate climates. This is Siberian white derain growing in the north of the forest strip of the European part of our country, in Siberia and the Far East. This shrub prefers wetter and wetter places along the banks of rivers, lakes, river floodplains and does not grow in the south of the steppe zone. Derain is red, blood dogwood, spread throughout the European honor of Russia, except for the Far North and the Caucasus, as well as central and southern Europe. This shrub lives in floodplains, thickets, undergrowth, and forest edges. And, finally, ordinary derain — dogwood, spread to the north to Orel.

Thus, it is argued that dogwood was 5–4 thousand BC grew only in the more southern regions of Europe, in the Caucasus and in Asia Minor, hardly correct.

Mulberry tree

A very interesting situation is developing with T.V. Gamkrelidze and V.V. Ivanov and with the name of the mulberry tree. They note that «the mulberry tree with dark fruits is a characteristic fruit tree of the Mediterranean and Southwest Asia; Western Asia is considered its ancient homeland. Large fruits… in a number of highlands of Central Asia and Central Asia (in the Pamirs) are used for food (flour is replaced from dried mulberry fruits, replacing flour from grain), the leaves go to feed livestock, and wood is valued as a building material. But in a number of Indo-European dialects that have lost the old word (like Indo-Iranian languages), the name of the mulberry tree is transferred to blackberries. So in Greece (where both mulberry and blackberry grow) they have one name — mjroi (already at Homer), and in Armenia mor, mori, moreni — blackberry (although the mulberry grows here too), the Latin „morms“ — mulberry, morum is the fruit of the mulberry tree and the blackberry.»