Remains of Rain

Soaked in morning dew

— remains of rain.

Alone in a Daydream

Absorbed in a daydream

— a young frog

alone by the leaf.

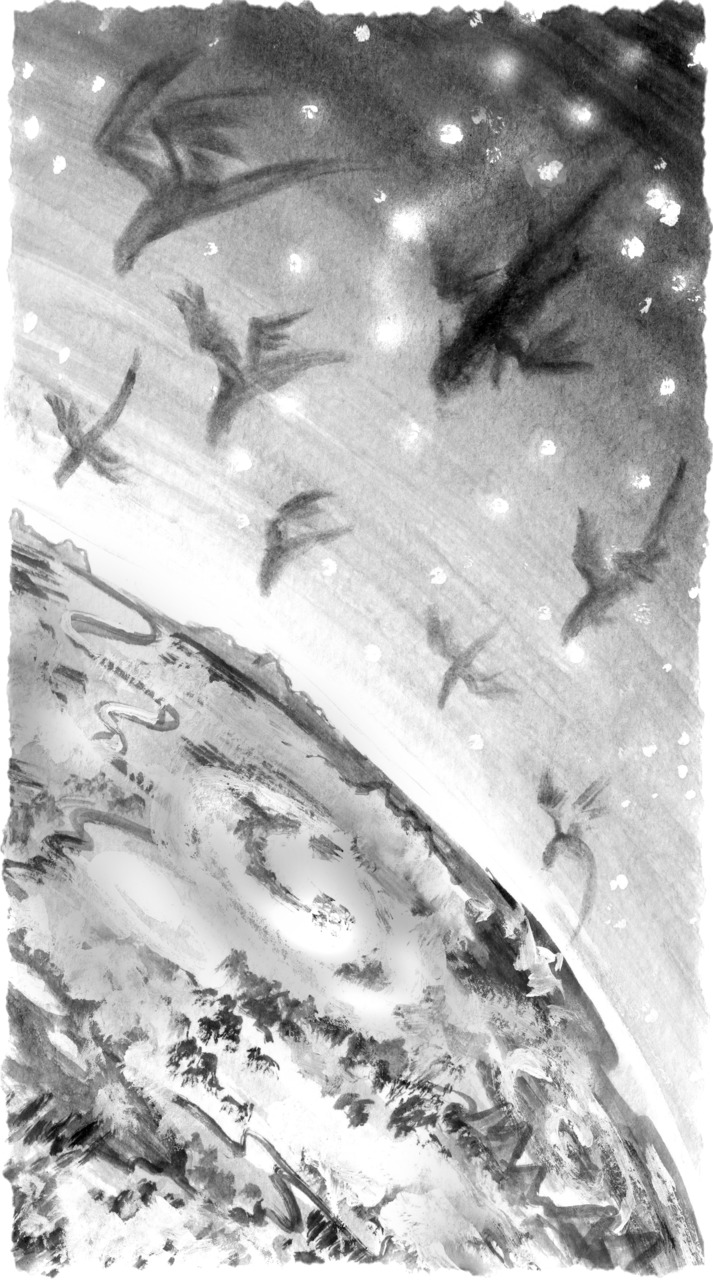

The Coming of Dragons

A very long time ago, when the world was still young and closer to the stars, whose light was strong and whose song could be heard in the deepest of caves, when the waters were still warm and not yet quelled, washing the formless shores, when many things were in their infancy, only to become great ages later — at the inception of all there came the dragons.

They came from beyond the borders of the world, where they had been traveling long and far, through regions of the void filled with nothing but ever-fading light and cold and emptiness, where time itself was running at once forward and backward, and space was incomplete and inconstant.

Exactly from how far away the dragons had come or where else they had used to abide, it was not known; they did not speak of this, neither among themselves nor to the wise. It had always been known that whenever the time would be about right for all lights of the world to fade, then the dragons would depart and be on their way, and never come back. It was said also that the dragons alone were aware of when it was meant to happen and were prepared.

Although the dragons traveled together, they preferred to dwell in solitude; upon coming each dragon chose a place to his liking and settled there all by himself. Some favored dark holes and bottomless pits, and some — mountaintops and gliding clouds, while others scouted for caverns on a seafloor, for wild woods and open fields.

Then again, some dragons were inclined to move with the world and went everywhere, observing the young things mature and occasionally having a word with their kin. Indeed, all the dragons watched keenly the world age; they marveled at the brevity of life, and remained the same and did not die, nor weakened. They never intervened with the common order of events, unless it was their fate to do so, and each dragon recognized his fate quite well. Not that he necessarily would accept it, for sometimes even the dragons were tempted; that, too, was their fate — to produce an example of lesser wisdom, without which true wisdom would fail to exist. It was rumored that some dragons became so corrupt they finally perished, but the wise had never shared such ignorance, as they understood that a dragon could not possibly perish — he could cease being a dragon. And that is what might have transpired.

The dragons looked patiently at the children of the world and were content, and waited. And the children sensed their presence and their vigilance, and there was no fear among them. Now and then someone brave enough and reckless enough would seek a dragon to ask for aid or advice, and could gain either or both, if one’s wisdom was equally sufficient. Many did not return, and those that did could not always put a dragon’s favor to a good use. Nonetheless, the dragons were talked about and revered, and sought after. And while they cared for nobody and nothing, they did not mind to act benevolently at one moment, as they did not mind to be cruel at another. They saw good and evil being invented; it was not them who invented either.

Of all those that dwelled in skies and seas, upon the earth or beneath it the dragons were the wisest and most beautiful, yet their wisdom and their appearance were not of this world but of somewhere beyond; it marked them as distinctly alien, and everyone around could feel that. Some dragons resolved to retain their demeanor, while others it pleased to assume forms more adjusted to the constraints of their new surroundings. Some dragons fancied to veil themselves with an exterior of neighboring creatures, among which they could walk unnoticed, for their own amusement, however ill-suited it might have been for a dragon to forsake his habits and powers for a long while.

The accounts of those that had actually glimpsed the true form of a dragon varied considerably; even so, several features seemed to be prevalent, relating, admittedly, not to the visible shape itself but to the impression it conveyed upon a spectator. At least one thing could be safely agreed upon — the dragons never presented themselves in a way they were expected to, and neither did their words nor doings.

No hierarchy or any kind of outward order was known to exist among the dragons. Freedom was their natural state of being, and although every dragon behaved as he saw fit for himself alone, his wisdom, both inborn and acquired, kept him from being troubled and troubling. Dragons never practiced any bondage with each other, nor could they see why so many of the lesser creatures were unable to live without it. In fact, the more sophisticated creatures were becoming, the less able were they to survive on their own; they united themselves in races and all sorts of co-habitation, while only the simplest were solitary. When united, some made up a whole lot of different illusions as a shelter from the world; soon they forgot they had made it all up and believed it, and dismissed everything else. In their blind pride and ignorance these creatures deemed themselves potent and omniscient; they meddled with both the ways of the world and their own fortune. This the dragons witnessed and wondered, though never involved themselves — the best action was the one not taken, and it was not their custom to alter the course of events.

The time passed. Many dragons grew weary and lost their interest in mundane things, and hid themselves from eyes of mortal creatures, and unmade paths that led to their places. They fell asleep and did not see the world save in their dreams; it was reckoned by the wise that the world itself was just a dream of the dragons — it would end when the last of them would have awakened. But it was not assumed with any certainty, nor may have been proved. For all that, many dragons stayed alert and continued to live as before, flying around, conversing with other creatures and contemplating essence of the existence, and waiting.

Not much more was to be learned concerning the dragons, whose wisdom and wont were not meant to be reflected upon; as one dragon was reported to have said, the sole way to learn was to unlearn. Hence, he that knows more than says should now hold his tongue and not speak whereof he should be silent.

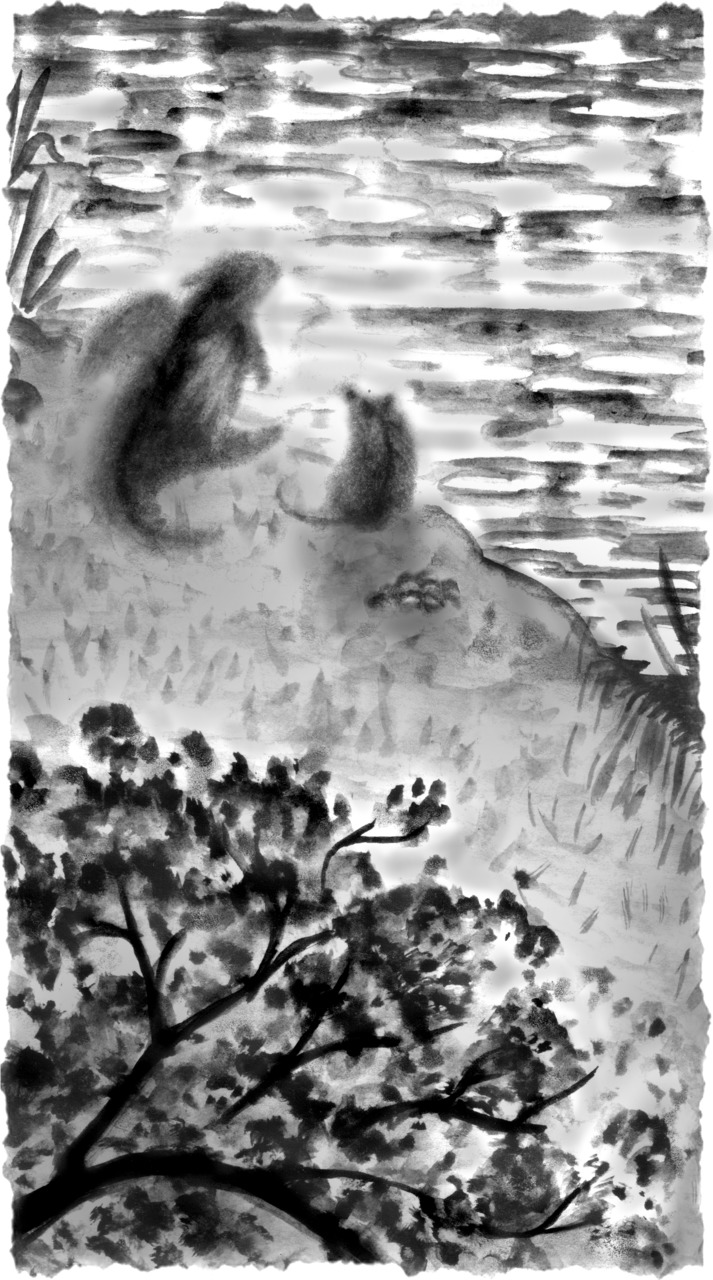

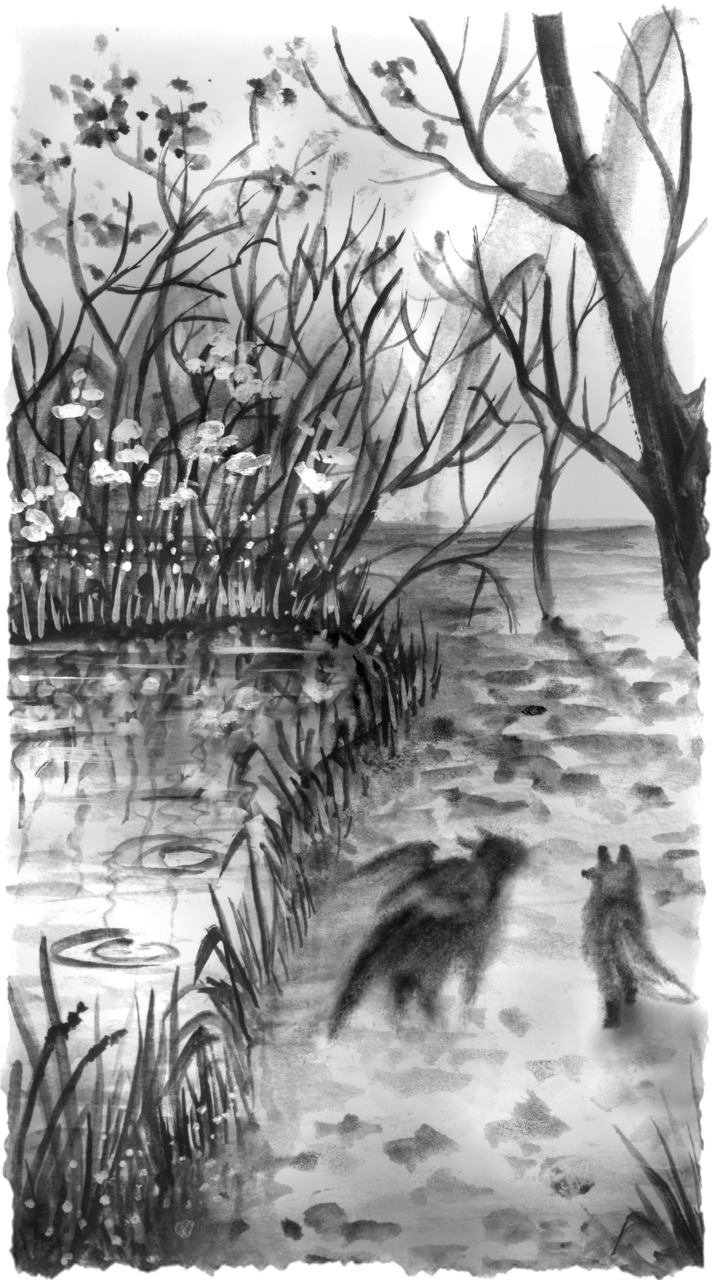

On a Riverbank

The Dragon and the water rat were sitting on a riverbank side by side. The water rat was throwing stones in the water, and the Dragon was watching quietly, along with a few curious — and not so quiet — birds on the branches above. The water rat’s skill appeared to be considerable, for more often than not a stone would make several jumps across the water before sinking down with a splash. The Dragon was unimpressed, evidently deep in thought; his gaze followed the stones all the same.

«You ought to show a little attitude, if you want them to jump over the surface,» remarked the water rat smugly.

«No need,» said the Dragon. «I am just watching.»

The water rat shrugged and, shooting him a furtive glance, went back to attend to its stones, gathered in a small pile. After a painstaking inspection it chose the roundest, most polished pebble and launched it with one swift motion. The Dragon was half-heartedly expecting some stones not to sink in the river eventually, but they all did, making him feel mildly embarrassed. He was not in the slightest perturbed — it was just somewhat dull when things kept occurring in a similar fashion.

There was rustling in the trees, and a forest bird darted to the river, chasing after a buzzing mosquito and missing; it circled back, crying mournfully in frustration. The mosquito, as the Dragon saw, was lurking in the grass on the other bank, apprehensive and hesitant to get back in the open. The splash from another stone sent it fleeing for a better refuge.

«I cannot imagine,» said the Dragon. «Why all of them must go down?»

«What else could they do?» The water rat eyed him suspiciously and tightened its grasp on a newly picked stone.

«Well, fly around or lie there on the water or dissipate in the air.»

«That is not what the stones do. At any rate, they are incapable of doing anything on their own accord, and I cannot make them fly around or any of that.»

«Maybe you can, but they cannot.»

«Same difference.» The water rat swung its arm.

«Is it now?» said the Dragon. «You are rather confident about that.»

«I am. Everything must have a reason. In real life a thing happens because some other thing has happened,» declared the water rat.

«Which thing?» said the Dragon.

«Any thing! And it happens all the time.»

«How could you know that?»

«Look, I throw this stone and it falls down.» The water rat snatched up a pebble and threw it; the pebble did not get very far. «See? It falls down because I threw it!»

«Next time it may not fall.»

«It is highly unlikely,» scoffed the water rat.

«What do you mean, unlikely?» said the Dragon. «It will either fall or it will not, there are no other options. Therefore, both are equally probable, since any action can occur only once.»

The river was flowing by, not in the least affected by the argument, its current steady. The riverbed, illuminated by the afternoon sun, was littered with rocks and debris, lying there stock-still, probably heedless of their whereabouts. Splinters of light danced from spot to spot, bouncing unevenly, pulling at occasional water spirits.

«It will fall,» insisted the water rat after a pause, tossing another pebble. «It always does. That is the rule. And a good rule is an offspring of a good experience. It is well to have the rules and uphold them. Saves time and effort.»

«It is apt, then, for those who wish to save their time and effort. Although, why would anyone desire that, I cannot say.»

«Eh?» The water rat was busy with its pile.

«Nothing has invariable value. No rule has invariable use. Also, you realize that you learn whether the rule is good enough only after you have applied it.»

«After the rule has proved itself useful we know its effect before the actual application.»

«It is guessing, not knowing. And you are free to make a guess about anything.»

«Some rule is better than no rule at all, would you not agree?»

«That scarcely makes any sense at all. How can you conceive a better new rule without breaking the old one? And to conceive any rules you should have no rules. But do not take my word for it.»

The water rat brooded about this, turning the idea different ways in its rat mind, shaping and reshaping it. It did not fit. And twittering of the birds was of no help either, distracting the water rat’s wandering attention.

«Rules notwithstanding, there is reality,» protested the water rat.

«So, something that repeats over and over is supposed to be real?»

«Yes, because it means there is some order there.»

«What has order to do with reality? And why cannot unreal things have order?»

The water rat was lost for words for a few moments.

«What is your point here?» it asked, defeated.

«There is none,» said the Dragon. «Now, what would you make of that?»

He picked up a large boulder and launched it straight up. Both he and the water rat watched it getting smaller and smaller, until it vanished completely. It never fell down.

«It does not fall.» The water rat was astonished. «Is it all real?»

«Whenever I throw things, they always fly off,» said the Dragon. «Why, I have no idea.»

«Why?»

«I have no idea.»

«I have not seen that before!»

«You have now,» said the Dragon and walked away with an air of conclusion. After a few steps he paused and added over his shoulder: «Experience, you see, makes no mistakes, unlike our judgment, when it expects to find something that is not there.»

Stunned, the water rat remained motionless, still clutching a pebble. It examined the ground, doubtfully, then the water and then the stone in its hands. «He might be right,» it thought. «It would be so more entertaining to have things behaving in a more manifold manner. Only, would it not be also confusing, being unable ever to predict it?»

The water rat loosened its grip and let the pebble slip from its little fingers. It fell with a thud.

The Dragon meanwhile strolled alongside the river, passing a few bends, until he came upon a comfortable spot, much like the one he had left. He found a lump of rock of decent proportions, weighed it solemnly. With a fluid motion he sent it plummeting at full speed lengthways the river, in the direction he had come from.

The rock was building momentum, traveling above the water, practically touching it. An instant, and it was lost in the misty distance. The Dragon never saw it fall.

«I am growing superstitious,» he thought.

Embers in the Storm

The color of fire

in the dark

of night.

Embers in the storm

— fireflies.

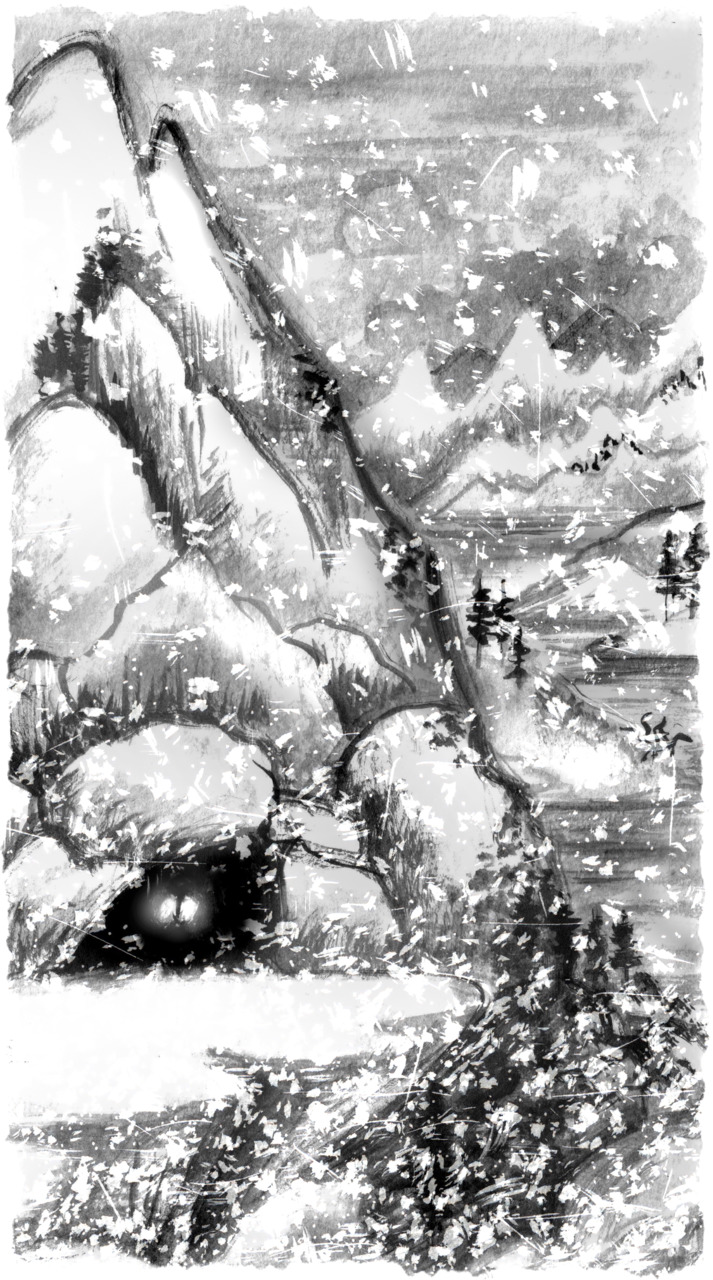

Snow All Around

The Dragon lifted his head and smelled the air in his cave, discreetly. Nothing was out of the ordinary, only familiar scents of stone, earth, wind and sunlight — the ones he was well accustomed to — and yet something was not as usual.

The Dragon opened his mouth and tasted the air with his tongue — again, nothing uncommon or exceptional. «What made me wake up?» thought the Dragon, and immediately he realized that it was the silence outside, the silence he had not encountered before, since he dwelt high in the mountains, where gales howled incessantly.

Uncommitted and unprejudiced, especially with so long a life he had lived, the Dragon lowered his head on the stone floor, fully intending to go back to sleep; but he could not. He decided he might come out and have a look at the sun or greet the adjacent peaks with his song. The Dragon now opened his eyes, the color of emerald, and surveyed the cave idly. Something was weird with the light, too — it did not exactly feel like sunlight, although the Dragon smelled one distinctly, and neither like moonlight nor starlight.

Wise as he was, the Dragon never cared about his wisdom, never pursued any knowledge, never searched for reasons for his actions. And of many strange things he had seen he could not remember a single one that did surprise him; for he always accepted things for what they were. When he found himself outside the cave and scanned the surroundings, he was not quite taken by surprise. Even though it was nothing he had confronted before, and it seemed positively peculiar.

The snow was falling so thickly, it was impossible for the Dragon to see the end of his own tail. And much worse — impossible to make out the sky, or the mountains, and worse still, impossible to hear their song. The snow, falling soundlessly, was muting all other sounds as well.

Given that the Dragon did not normally distinguish beautiful from ugly and pleasant from distasteful, he did not find the snow appealing. For one point, it was not singing, for another, it had no smell; and how could one understand the true quality of so incommunicative a thing!

Then the Dragon thought that, perhaps, the snow was no more expecting to meet him than he expected to meet the snow; he tried a welcoming song but soon broke off, for he felt the snow was not listening. «So be it,» said the Dragon to himself. «It will stop going down and the horizon will be in sight again.» He went back to the cave.

The snow was not stopping. It was falling all the next day, and the day after that, and the day after. The Dragon did not count the days — he never measured time in such short paces. He only sat and gazed at the snowflakes.

«No thing can go on forever,» he thought. «Who knows that better than me?»

So he gazed, entranced by slow and subtle dance of the white. The snow was sparkling and glittering in the air, swirling in circles in a light breeze, and was coming down on the Dragon’s wide-spread wings.

«Maybe it is coming from the stars,» thought the Dragon. But with clouds extending from one horizon to another he could not see the stars. Many were good friends of his, and he missed their song, their shining, their whispering in his dreams. He decided to pay them a visit. He stretched his huge wings, hit the nearest snowdrift with his tail and breathed out a long golden flame, melting all the snow up to the edge of a precipice, the rest cascading lazily on the sides.

The Dragon looked up once and jumped into the air, waving unhastily, and in several powerful strokes found himself high above his mountain, which was glazing silver instead of dark gray, with a newly cleared passage already disappearing.

The Dragon rose up and up, until he virtually reached the clouds; the higher he ascended, the fiercer was becoming the snowfall, when finally it was going so dense that the Dragon lost his bearings, blinded and deafened by the white whirlpool. He struggled, strong as he was; the force of the snow was stronger. Fatigue was taking hold of his body, but for the time being he was loath to give up — there was a price to be paid for chance.

Like all his kin the Dragon could see his future as plainly as his past, not as a design of events but as a flowing of his inner feeling. Like all the wise he knew that when the time came, his feeling would conduct him to the path of his true fate. Therefore, in following his cravings and fulfilling his will the Dragon lived his destiny, caring not for danger or destruction. He struggled more.

Yet, excessive persistence was not by its own nature a way of success — this the Dragon knew only too well, especially from the days when he was the young Dragon. He was by no means troubled to succeed — that was a devotion for lesser creatures; he merely beat his wings against the storm.

For all one knew, there might have been a reason behind, or possibly an aim ahead, or neither, or both at once. The wise did not seek answers where there were no questions. Believing was enough. The Dragon believed nothing and everything. And believing did not necessarily imply understanding — the Dragon was not that foolish as to believe in what he did not understand or to understand what he believed in.

Was not the world itself a product entirely of his own imagination, after all? The stars existed because he could see them. The snow was cold because he could feel it.

Nothing was true beyond doubt.

And doubt killed faith.

And without faith there was no truth, for they were one.

The Dragon gave up. He returned to his cave and went back to sleep. In the morning, after singing a greeting to the burning dawn, the Dragon dimly recalled having had the most curious dream.

Restless Winds

In a season of falling leaves it was especially tranquil at the foot of the mountains. Northern winds had been rising steadily, getting more robust with each passing day, bringing with them damp coolness and sweet fragrance of decay. Bare branches stood out crisply off the sky, seen from below as an intricate labyrinthine pattern, framed by the flashes of the clinging foliage. Most birds had departed for warmer regions, and most ground-dwellers had been busy tending to their hideouts; the air was still but for the wails of wind and creaking of tree-trunks.

These days the Dragon took a habit of having a walk in the woods, and a secluded pond there was his final destination. He appreciated its placid waters and overgrown shores, its sentinel trees and patches of the blue reflected on the surface — a world within a world, embracing itself before the oncoming cold. He inhaled deeply and held his breath.

«How can wind bend a tree? It is just a wind,» a voice of a duck quacked to his left.

«It bends a tree,» said the Dragon without looking. «Do not forget about that.»

«Is it a riddle of some sort?»

«A riddle arises as soon as one has said it; when one has solved it, it is gone.»

«Sometimes it is not,» complained the duck. «For instance, I cannot enter the same wood twice. After I got out, it has changed and is not the same wood anymore.»

«Too bad for you,» said the Dragon sympathetically.

«It is not so bad,» intermitted another duck’s voice. «I cannot enter the same wood even once, for it is changing while I am entering it.»

«You enter the wood,» said the Dragon. «Is it not what matters?»

«Let me ask you something. When you come to this wood, is it the same wood for you and for us three?»

«It is the same for me, I dare say.»

The Dragon glanced at the ducks, which were circling lazily in the pond, their tiny legs working steadily in the shallows. Only two were present.

«You mentioned there were three of you.»

«There are three of us.»

«Where is the third?»

The duck pointed, and the Dragon could see a ginger shape lying in a heap on the ground, surrounded by a few feathers. It was furry, spread-eagled and in considerable dishevelment. Of all things it came closest to a dead fox.

«It is a dead fox,» said the Dragon.

«The fox ate the duck,» explained the duck.

«Did the fox die after that or before?»

«It was already dead when we all got here.»

«It must be quite alive by now,» said the Dragon.

In the meantime the fox indeed grew tired of being dead. It lifted an arm tentatively, then a leg, wiggled its ears and after a short hesitation bounced energetically. The ducks, scared, took off promptly, crying in alarm. The Dragon looked at the fox, and the fox looked back with some insolence; they both started strolling along the shore.

«How do you like lilies?» said the Dragon. «They are splendid this time of year, especially those that sprout on the water.»

«I see no lilies on the water,» objected the fox. «None.»

They passed several water-lilies, and the Dragon indicated one:

«See? That is what I was talking about.»

«It is not a lily but a water-lily,» remarked the fox irritably.

«I often mean water-lily when I say lily,» said the Dragon. «Any sign is arbitrary before it is applied. Only afterwards it gains meaning that it lacked previously, and that connects it to the thing it represents; they both almost become one.»

«If a sign gets extra meaning, it becomes another sign altogether.»

«Almost, I said.»

The fox prickled its ears at a far-off sound and appeared to listen intently.

«And my sign and your sign might not be the same.»

«I know nothing about any signs,» said the fox with a dreamy expression on its face. «But that duck was exceptionally delicious.»

«To see that, I do not have to look.»

«You are able to see without looking?»

«Do you want to try me?»

«All right. How many eyes have you got?» inquired the fox.

«A pair of them, I suppose,» said the Dragon absent-mindedly.

«Did you count?»

«I told you, dragons do not have to. Our very ability to think and to talk is all about replacing things with ideas, with signs.»

«An idea of a thing is not its perfect image!» protested the fox.

«Just so. It needs to connect, above all, with other ideas and only so much with the thing itself. New ideas are thus determined by old ideas and cannot exist without them.»

«Unlike new things.»

«That is immaterial. When we think we talk about a thing, we really talk about an idea of a thing.»

«A thing precedes an idea, no?»

«I would not put it precisely like that,» said the Dragon.

The sun was setting and the sky was turning purple. The shadows were creeping upon the water of the pond, drinking colors from whatever they touched, dissolving outlines, softening shapes. The night-time was upon the woods.

«A single idea does not suffice. The best idea can come from many good ideas. And good ideas come from many ordinary ideas.»

«What about your ideas?» asked the fox critically.

«If you understand me at all, you recognize them as senseless.»

«Surely that is a contradiction.»

«To contradict each other, ideas must have something in common,» said the Dragon. «Otherwise, they cannot be compared effectively. The world is different for us, how more so our ideas!»

«In this respect they are all similar, are they not? I wonder, may it be possible for some ideas to be more similar than others?»

«Any idea may be of an advantage, if that is what you are asking about. Besides, the merit of an idea can only be stated in comparison with another idea. Any idea can be compared only with other ideas. Whether it should be — that is a separate issue.»

«I thought it was your point,» yawned the fox.

«You cannot understand an idea without the support of other ideas, and other ideas without the support of each other. Advancing with one idea, you increasingly depend on another. Consequently, your understanding improves as a whole but declines with any given instance. To understand everything is to understand very little.»

«And the moral of this?» asked the fox, exasperated.

«You do not need me to tell you,» said the Dragon.

Beyond the Sea

Gray skies.

Gray clouds.

Remote waterfront,

awash with the sound

of waves.

At the edge —

stars beyond the sea.

Rising.

The Tides of Night

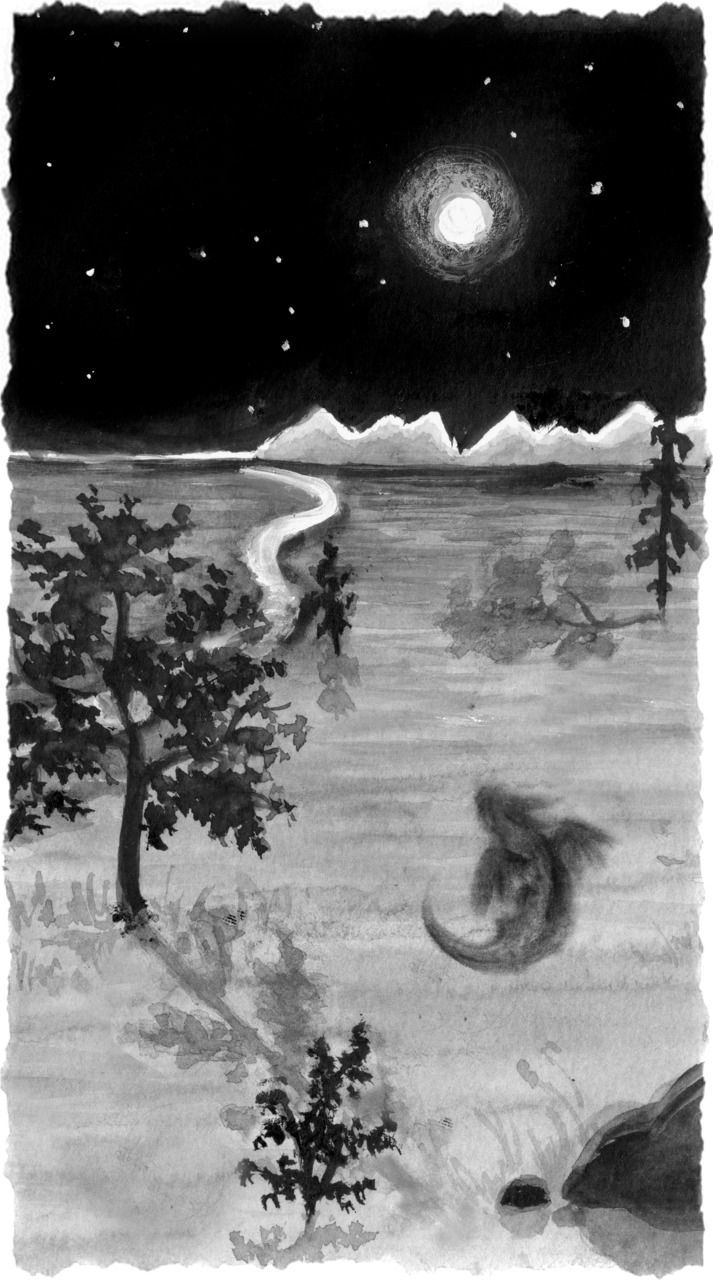

Eternal darkness of the void beyond seeped into the world at the beginning to become night.

Indeed, the darkness was the world; for ages it had reigned unchallenged and pure, unmarred by light, hidden inside itself, until some star a distance away caught sight of it, and then another, and the corruption commenced.

The darkness strained and strived, foreseeing that it might prevail in the end, even if vanquished at the moment. The light tore at it, banished it, and the darkness suffered, and its loss was great. It kept coming back, always, yet was no longer able to endure. Irresolute and restive, it shifted from one place to the next, all the while repeatedly forced to give up what it had just reclaimed.

Thus the night and the world were divided.

Before, the void beyond had nurtured the night, its favorite progeny, and had sent shadows to act upon its behalf, shadows inseparable both from the night itself and the dark world it engulfed. Now, disconnected, in torment, they gained shapes in wavering starlight and grew distinctive and independent, guarding the night and guiding it from harm.

The shadows found themselves familiar with the dragons, who took no sides, for whom both the darkness and the light were alike. They traveled and they conversed, they ran together and flied together, and sometimes could be mistaken for each other, to mutual amusement.

Many creatures and things of the dark, however, changed their allegiance and were transformed, led to light and to life, but not the shadows, which remained unto themselves. They were all different at first, and neither their appearances nor desires nor doings were remotely the same. They inhabited disparate regions and seldom met in an encounter. They harbored secretly an aversion to each other, as did the darkness and the light.

A ravenous fiery star of extraordinary brightness once drifted from far off and preyed upon the darkness of the world, crippling it with searing shine. The shadows perished in numbers uncountable, were reborn, and perished anew; but the star never withdrew. Insatiable though it was, it could not devour the darkness wholly — from what was left the night and its shadows emerged time after time, weakened but unbroken for all that.

On these occasions, with the fiery star done for the day, the night was able to roam free, unchecked. It swept over the waters and the lands, and filled the air, reuniting the world with the void beyond. It was neither cool nor warm, dry nor wet, supple nor rigid, and it was everywhere. The night was everything, and everything was the night, albeit briefly.

The stars, myriads of them, flickered on all sides, piercingly visible, illuminating nothing. Their soundless songs rushed by and across like currents in an ocean, coalescing into a single celestial harmony of many facets and layers, driving a listener mad and stealing one’s very self.

The dragons did not listen, or if they did, they made no resistance whatsoever. They did not care not to be themselves anymore, or for anything to be anything, for that matter. The tides of night took them across the sky and the stars, holding them firmly in their grip, and the dragons were aware of this firmness, of the steady pulse that ran through the night, of the heartbeat of the void echoed in the rising and falling black waves.

Had any of them glanced sideways, they would have noticed other phantoms, all sliding noiselessly ahead, farther and further — more dragons, all indifferent to the presence of the others, all submitted to the power of night. Their minds were vacant, their senses detached, and night was with them and within them.

More stars began to arrive whenever their fiery kin abated, and some stayed. They had no light of their own, no hunger; instead, they chose to reflect any light that came their way and mutilated the darkness with pale glow nonetheless. Only the clouds provided an incidental relief. Yet, the ancient balance was destroyed. The night of the darkness ebbed and flowed in relentless tides, never at peace, biding its time ever since.

As for the shadows, they were bound to the custom of the world and so restrained. They were made to mimic, as if in a kind of dream, whatever creature or thing they approached and to be at the mercy of all the stars and fires, and any other light there may have been. They were deprived of their strength and of their form, reduced to bear the uneven shape of the others, devoid of color or substance, constantly driven to no escape and brought back. Only the dragons had no part in that and still conferred with the shadows on equal terms, as of old.

It would not last interminably, the night knew. The world had belonged to it, and it would again, at least for some time. Sooner or later the voracity of the fiery star would be quenched, its strength spent. The lightless stars would be of no significance and the distant ones would lose interest. And the shadows, released belatedly, would see to the rest.

It would start slowly, gradually.

In the blazing radiance a faint, faint shadow would go astray, its outline blurred and resembling nothing certain. Another shadow elsewhere would disappear altogether. The night itself, perhaps, would linger a moment longer than regularly. And faraway lights would dissolve before making it all the way through.

The dragons would read the omens and understand but would not interfere. They would only observe how the shadows turned less and less passive, how they imitated their counterparts less and less faithfully, and how the living creatures and things of the light declined and trembled, recalling where they had come from, unwilling to return.

At one point the darkness, eternal darkness of the void beyond, would flood the world to become night. Many would drown, but it would be as it had been before, cleansed and inviolate. The darkness would be the world, would reign unchallenged and pure, hidden inside itself.

And the dragons would glide on its tides once more and revel.

Of Fishes Large and Small

Бесплатный фрагмент закончился.

Купите книгу, чтобы продолжить чтение.