Бесплатный фрагмент - Biblical Chronology

Foreword

Throughout centuries, numerous attempts have been made to recreate biblical dates and chronology. Yet there is still no consensus in this regard — for various reasons. This book briefly discusses the problems of the Old Testament chronology and provides a more detailed timeline of the era of Jesus Christ. The main flaw of the various existing versions of the New Testament chronology is that they do not completely align with the Four Gospels and the historical evidence. To solve this problem, we had to re-create all the chronological calculations to see how well they correlate with each other. The results was highly satisfactory. The calculations and explanations presented here are simple, so anyone can verify them. In conclusion, the book addresses some of the issues related to reforming the Church calendar and suggests possible solutions.

Section 1. The basics of chronology

Calendar systems

Chronology is always based on a certain calendar. And calendars are based on solar and lunar cycles. This simple truth we find in the very first pages of the Bible:

“And God said, Let there be lights in the firmament of the heaven to divide the day from the night; and let them be for signs, and for seasons, and for days, and years: And let them be for lights in the firmament of the heaven to give light upon the earth: and it was so. And God made two great lights; the greater light to rule the day, and the lesser light to rule the night: he made the stars also. And God set them in the firmament of the heaven to give light upon the earth, And to rule over the day and over the night, and to divide the light from the darkness: and God saw that it was good. And the evening and the morning were the fourth day” (Gen 1:14—19).

There are three types of calendar systems: solar, lunar and lunisolar. These systems have engendered many types of calendars. Below we will consider only those that are necessary for recreating the biblical chronology.

The Julian calendar

In 46 BNE (Before New Era), the Roman calendar was reformed by Gaius Julius Caesar (100 — 44 BNE). This solar calendar was based on the average duration of the year equal to 365.25 days. Since the calendar year can only consist of a whole number of days, it was agreed that the standard year would consist of 365 days, and every fourth (leap year) would be 366 days. The calendar was introduced on January 1, 45 BNE — on a new moon. In the days of Octavian Augustus (63 BNE — 12 NE), the Julian calendar underwent slight modifications and since then was used in a fixed form in many countries, until it was replaced by the Gregorian calendar.

The duration of the months in the Julian calendar is as follows: 1. January — 31 days, 2. February — 28 days (leap year — 29 days), March — 31 days, 4. April — 30 days, 5. May — 31 days, 6. June — 30 days, 7. July — 31 days, 8. August — 31 days, 9. September — 30 days, 10. October — 31 days, 11. November — 30 days, 12. December — 31 days.

In the age of Jesus Christ, the Julian calendar was in wide use. Later this calendar was adopted by the Christian Church. In light of this, and also because of its simplicity and convenience, we will primarily use the Julian calendar dates in making our calculations.

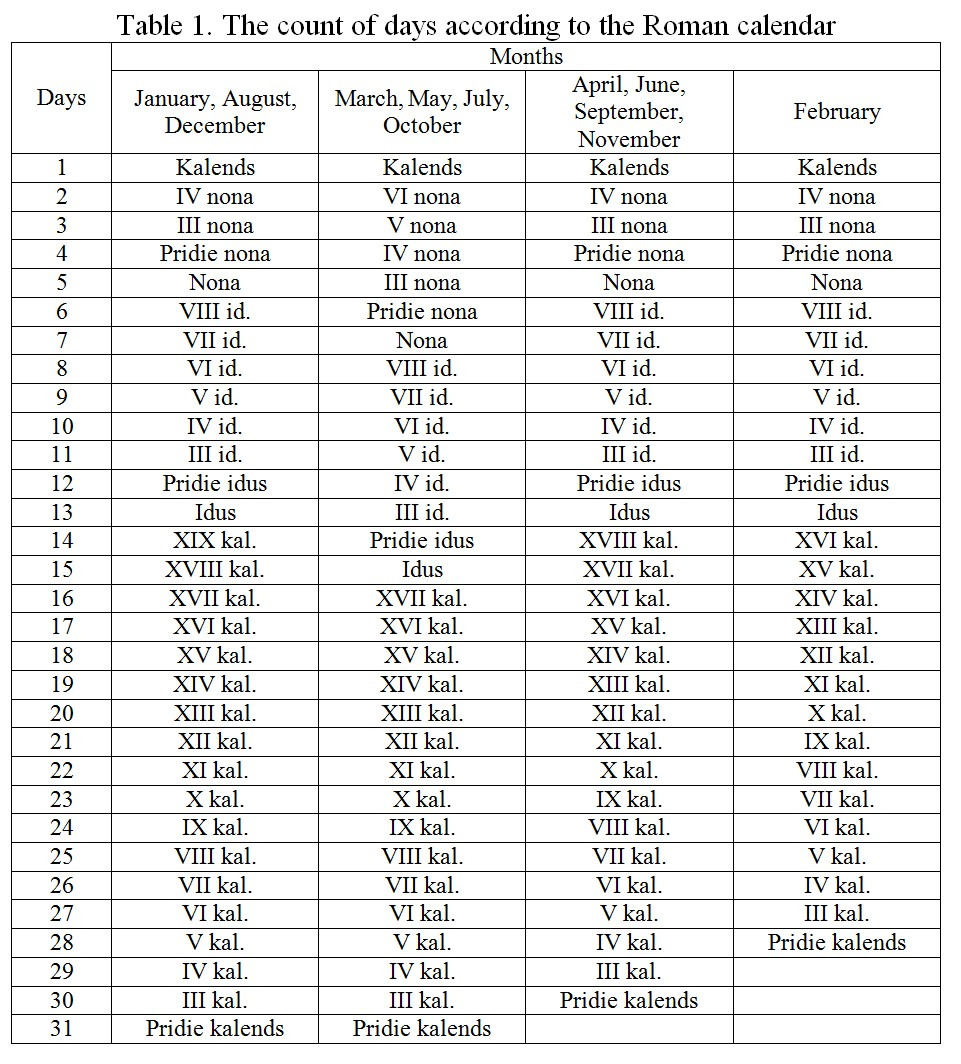

Counting days according to the Roman calendar

The ancient Romans used a special system for counting days in a given month. The first day of the month was called “calends” (calendae or kalendae). The middle day of the month was called “idus”. The ninth day before idus was called “nona” (nonae), counting inclusively. Initially, calends, nones, and idus roughly coincided with the new moon, the first quarter of the moon, and the full moon, respectively. With time, however, this correlation was broken. Yet the traditional naming of days in this way remained intact for a long time. The day before calends, nones, and idus was called “eve” (pridie). The remaining days were numbered in the reverse order: so many days before nones, idus, or calends. In the leap year, an additional 366th day was inserted between February 23 and 24. It was called “bis sextum kal. Mart” (“twice sixth before the March calends”). The year was called “annus bissextus”, from which the term “bissextile year” or “leap year” is derived.

This system of numbering days was used for a long time, even after the reform of the calendar by Julius Ceasar.

Reference points

We have already touched upon the NE designation in relation to the numbering of years (it means “from our era” or “from the new era”). Historically, this reference point was called “the year of Our Lord” (Anno Domini or AD). The origin of this designation is ascribed to the monk Dionysius Exiguus (c. 470 — c. 544 NE). Later it became obvious that Dionysius had made a mistake in his calculations, but the tradition of counting years from this reference point was not discontinued. We will also stay within this framework as we proceed in our study, and all the dates that you will see in this book will correlate with this system, unless otherwise stated. For more information about the era of Dionysius Exiguus see Section 3. In the meantime, let us note that all the years following this reference point are designated as NE (AD), and the years preceding it are designated as BNE (BC). In other words, the 1st year NE is preceded by the 1st year BNE. It is normal for this type of count (historical or chronological), where the “zero year” is absent. But since such a way of counting is not always convenient, the so-called “astronomical year system” was introduced, where the 1st year BNE corresponds to the zero year, the 2nd year BNE corresponds to the -1 NE, and so on. This method is better suited for calculations in general.

Before the introduction of the Anno Domini (AD) designation, there were other reference points too. There were chronologies based on the year of the Olympic Games, as well as on the year since the foundation of Rome, since the beginning of the emperor’s reign, and since “the foundation of the world” (several versions), etc.

Counting days since the foundation of Rome

Before the Era of Dionysius (AD), chronology was often based on the “since the foundation of Rome” reference point. It was called “ab urbe condita” (“since the foundation of the city”). This reference was popularized by Mark Terentius Varro (116 — 27 BNE), and it corresponded to April 21, 753 BNE.

To convert a year “since the foundation of Rome” (a.u.c.) into the year NE, the following formula was used:

R = auc — 753

For example, 750 a.u.c. corresponds to -3 NE according to the astronomical system, or 4 BNE.

Counting days based on Olympic years

One other way of time keeping in the ancient world was to count years relative to the Olympic Games. Since the Olympiads were held once every four years, the years were designated as “the first” (second, third, fourth) since the year of a specific Olympiad. The reference point for the first year of the first Olympiad corresponds to July 1, 776 BNE.

To convert a year based on the Olympiad into the NE system, the following formula was used:

R = [(Ol — 1) * 4 + (t — 1)] — 775,

where “Ol” is the number of the Olympic Games, and “t” is the number of the year since the Olympiad.

For example, the 4th year of the 48th Olympiad (Ol. 48.4) converts into -584 NE, or 585 BNE. This was the year of the eclipse of Thales (see Pliny the Elder. Natural History, 2,12).

The Egyptian calendar

The Roman calendar was a modification of the Egyptian calendar. A number of ancient writers (mainly from the church of Alexandria) continued to use the Egyptian calendar even after the Julian calendar was in wide use.

The Egyptian calendar consisted of 12 months, 30 days each. The Greek names of the months are as follows: 1. Thoth, 2. Phaophi, 3. Athyr, 4. Choiak, 5. Tybi, 6. Mechir, 7. Phamenoth, 8. Pharmuthi, 9. Pachon, 10. Payni, 11. Epiphi, 12. Mesori.

At the end of the year, five more days were added, which were called in Greek “epagomen”. So, there were the total of 365 days in the Egyptian calendar year.

Claudius Ptolemy (c. 100 — c. 170 NE), the ancient Greek scholar, is credited with tracing the beginnings of the Egyptian calendar down to the enthronement of the Babylonian king Nabonassar. The reference point of the Nabonassar era (1 Toth) corresponds to February 26, 747 BNE.

The exact alignment of eras

Based on the above, the following equasion can be suggested:

1 NE = 754 a.u.c. = Ol. 195.1 = 748 Nabonassar

As you may have noticed, the formulas for converting dates between different chronologies are approximate; they do not account for the differences between the times of change from one year to the next for the specified eras. Using these formulas, the calculations can sometimes be off by a whole year. To avoid it, it is necessary to take into account the exact date of an event (day and month), so you can make adjustments in the process of calculations.

The Egyptian calendar is even more challenging. At first, it doesn’t seem very complicated, because we know that January 1 of the year 1 NE corresponds to Tybi 12, 748, of the Nabonassar era. However, the Egyptian year consists of 365 days, whereas the Julian calendar year is 365.25 days. That is why every 4 years these two calendars get adjusted against each other by one day. The process of converting Egyptian calendar dates into the corresponding Julian calendar dates will be explained in later chapters.

Since the foundation of the world

In the first ages of Christianity, attempts were made to count years since the foundation of the world, or from Adam. Annalists made their calculations based on the Old Testament data but came up with varying results, for which reason this type of chronology was not widely accepted. Partcularly, the scholars disagreed on how much time had passed from the Babylonean exile of the Jews (6th century BNE) up to the New Testament events, because the Bible does not cover this chronological period. So they had to use external chronicles, which were not always reliable. Only several versions of the eras “since the foundation of the world” have any historical significance:

The Antioch era (reference point: September 1, 5500 BNE, Friday). Developed by the bishop Theophilus of Antioch, circa 180. Some sources give other reference points: 5969, 5515, or 5507 BNE. But they were not used in the chronicles.

The era of Hippolytus of Rome (reference point: 5503 BNE). Appeared around the year 200.

The era of Sextus Julius Africanus (reference point 5502 BNE). Appeared around 220; used in “Chronography”.

Theophilus, Hippolytus, Julius and other ancient writers believed that the period of time between Adam and the New Testament (Jesus Christ) was 5500 years. The basis for this belief was the biblical account of the creation of man in the middle of the 6th day (Gen 1:24—31), and also the words of Scripture: “For a thousand years in thy sight are but as yesterday when it is past” (Ps 90:4 [Ps 89:5 rus]), and: “But, beloved, be not ignorant of this one thing, that one day is with the Lord as a thousand years, and a thousand years as one day” (2 Pet 3:8). There were often discrepancies in these eras as to the date of Christ’s birth. Some scholars believed that 5500 years was an approximate marker — the Bible does not conclusively say that Adam was created exactly in the middle of the 6th day. So deviations from this date were allowed. There were also some who counted 5500 years from Adam’s fall, not from the foundation of the world. Other denied any correlation between the millenia on the timeline of history and the number of creation days.

The Old Byzantine era (reference point: 5504 BNE). Used in Byzantium until the 4th century. Also used in the ancient Rus and Bulgaria.

The Byzantine era (reference point: September 1, 5509 BNE, Saturday). Introduced under the Emperor Constantius in the 4th century. It was used in Byzantinum up to the 6th century, and in Russia starting with 15th century. The reference point was shifted so that the indiction numbers would be easier to find. For the year 5509 BNE, the indiction numbers equal one. For the succeeding years, the indiction numbers are the remainder of the division of the Byzantine date by 28, 19, and 15. The remainder value equalled to the circle of the Sun, the Moon and the indiction, respectively.

The era of Panodorus of Alexandria (reference point August 29, 5493 BNE, Tuesday). Introduced by Panodorus of Alexandria around the year 400.

The era of Annianus (reference point: March 25, 5492 BNE, Sunday). introduced by Annianus of Alexandria in the beginning of the 5th century.

The era of Alexandria (reference point: September 1, 5493 BNE, Friday). It is a modification of the eras of Panodorus and Annianus. Used by the Byzantine historians.

The March Byzantine era (reference point: March 1, 5508 BNE, Friday). Used in Byzantium starting with the 6th century, and in the ancient Rus up until the 12th century.

The Ultramarch Byzantine era (reference point: March 1, 5509 BNE, Thursday). Used in the medieval Rus, between the 12th and 15th centuries.

The eras “since the foundation of the world” were so numerous that annalists often gave their dates in several chronological systems — to avoid confusion.

The Jewish calendar

We know very little about the original Jewish calendar. Four months of the ancient calendar are mentioned in the Old Testament: Aviv [Abib] (the first month, the month of ears of corn) [Ex 13:4], Zif (the second month, month of blossoms) [1 Kings 6:1], Ethanim (the seventh month, the month of strong winds) [1 Kings 8:2], Bul (the eighth month, the month of the harvest) [1 Kings 6:38].

While in Babylonean captivity, the Jews adopted the lunisolar calendar of their captors. It is easy to verify by comparing the names of the ancient Babylon months with the contemporary Jewish calendar.

The names of the ancient Babylon months: 1. Nisannu, 2. Ayyaru, 3. Simanu, 4. Duuzu, 5. Abu, 6. Ululu, 7. Tasritu, 8. Arahsamna, 9. Kislimu, 10. Tebetu, 11. Sabatu, 12. Addaru.

The names of months in the late Jewish calendar: 1. Nisan (former Aviv), 2. Iyyar (former Zif), 3. Siwan, 4. Tammuz, 5. Ab, 6. Elul, 7. Tisri (former Ethanim), 8. Marheswan (former Bul), 9. Kislew, 10. Tebet, 11. Sebat, 12. Adar.

In the ancient Jewish world, the appearance of the first crescent in the evening sky, which was called “neomenia”, marked the beginning of the month. The moment of neomenia was simply observed, and then the beginning of the new month was announced. So, there were 29 or 30 days in a month. The standard year had 12 months. But since the tropical (solar) year consists of 12.36826 synodic (lunar) months, the inaccuracy added up over time and had to be eliminated by adding an extra month. Whether there was a need for the extra month was determined based on the conditions of the grain crops and the age of the sacrificial animals — after all, the Passover law had to be observed: “In the fourteenth day of the first month [Nisan (Aviv)] at even is the LORD’S passover… Ye shall bring a sheaf of the firstfruits of your harvest unto the priest: And he shall wave the sheaf before the LORD, to be accepted for you: on the morrow after the sabbath the priest shall wave it. And ye shall offer that day when ye wave the sheaf an he lamb without blemish of the first year for a burnt offering unto the LORD” (Lev 23:5, 10—12). That is why the year had to be extended by one month if the grains were not ripe, and the lambs too young. The extended 13-month year was usually called embolismic.

Around 500 NE, the Jewish calendar was reformed. The beginning of the year was moved to the month of Tisri, and Molad became the starting point for counting months (the astronomic new moon). Also, specific rules were introduced for alternating the number of days in a month and adding an extra month, which facilitated the process for calculating dates.

The reference point of the Jewish calendar was moved to the foundation of the world, Tisri 1 (“the new moon of creation”), which corresponded to October 6/7, 3761 BNE in the Julian calendar.

The principles of the Jewish calendar

In the Jewish calendar, the 13th month was inserted according to the 19-year cycle: specifically, for years 3, 6, 8, 11, 14, 17 and 19. The extra month was added before Adar and was called Adar 1 (Adar Rishon). Adar, then, became the next month and was named Adar 2 (Adar Sheni, Adar Bet, Beadar). All the religious feasts of the month of Adar were transferred to this month.

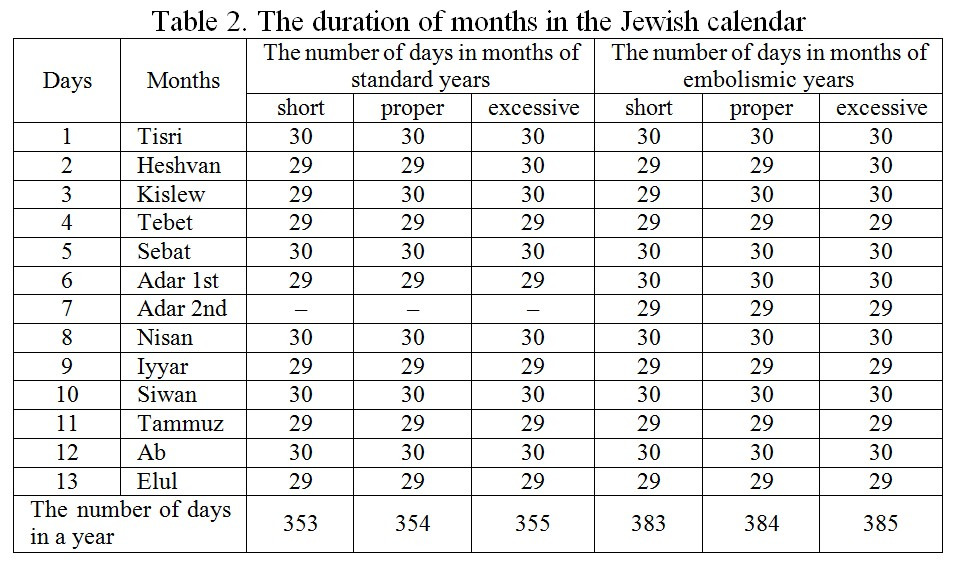

The number of days in a year varied from 353 to 385. There were six variants:

a) short, or insufficient year (hasarin) had 353 days (standard) or 383 days (embolismic);

b) the proper, or full year (kesedran) had 354 days (standard) or 384 days (embolismic);

c) the excessive year (shalamim) had 355 days (standard) or 385 days (embolismic).

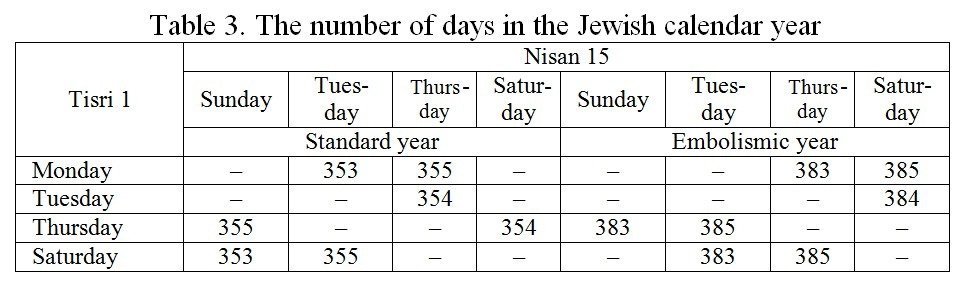

The rationale behind such a complex system is the desire of the Jews to observe all the Talmudic religious traditions. It is only possible to fulfill the several hundreds of Talmudic prescriptions if the 1st of Tisri (the beginning of the new year) falls on Monday, Tuesday, Thursday or Saturday, and the 15th of Nissan (the Jewish Passover) falls on Tuesday, Thursday, Saturday or Sunday.

So, in any given year, if you know which days of the week fall on the 1st of Tisri and the 15th of Nissan, you can understand whether the year is insufficient, proper or excessive, that is, you will know how many days it consists of.

One other percularity of the Jewish calendar is that 24-hour days are counted from sunset, not from midnight. This was believed to be the pattern of creation in the corresponding Genesis account: “And the evening and the morning were the first day” (Gen 1:5).

The formulas of Gauss

Around the year 1800, the German mathematician Carl Friedrich Gauss (1777 — 1855) introduced formulas for calculating the dates for Christian Easter and the Jewish Passover. These formulas made chonological calculations much easier.

The procedure for calculating the date of the Jewish Passover (Nissan 15) is as follows:

1) A=R+3660,

where “A” is the year according to the Jewish calendar; “R” is the year NE.

2) a= (12A+17) mod 19,

where “mod 19” is the remainder of the division by 19.

3) b=A mod 4.

4) M+m= (32,0440933+1,5542418a+0,25b-0,00317779A),

where “M” is the integer part, and “m” is the fractional part.

5) c= (M+3A+5b+5) mod 7.

So, three variants are possible:

1) is c=1, a> b and m≥0.63287037, then the Jewish Passover (Nissan 15) falls on M+2 March in the Julian calendar.

2) if c=2, 4 or 6, and also when c=0, a> 11 and m≥0,89772376, then the Jewish Passover falls on M+1 March.

3) in all other cases it falls on M in March.

If the resulting value is greater than the number of days in March, you should subtract 31. The result will correspond to a date in April.

For example, let us calculate the date for the Jewish Passover in 2016:

1) A=5776.

2) a=17.

3) b=0.

4) M+m=40,11128886.

M=40, m=0,11128886.

5) c=6.

Since c=6, you should add 1 to M=40 and subtract 31. So, in 2016, the Jewish Passover (Nissan 15) falls on April 10 in the Julian calendar, which corresponds to April 23 in the Gregorian calendar. As noted above, the 24-hour day in the Jewish calendar begins at sunset. That is why the 15th of Nissan in this case begins in the evening of April 9 and ends in the evening of April 10.

The procedure for calculating the date of Christian Easter using the Gauss formula is as follows:

1) a=R mod 19,

where “R” is the year NE; “mod 19” is the remainder after the division by 19.

2) b=R mod 4.

3) c=R mod 7.

4) d= (19a+15) mod 30.

5) e= (2b+4c+6d+6) mod 7.

Three variants are possible:

1) if the sum of (d+e) does not exceed 9, then Christian Easter falls on March (22+d+e).

2) is (d+e) ≥10, then Easter falls on April (d+e-9).

For example, let us calculate the date for Easter in 2016:

1) a=2.

2) b=0.

3) c=0.

4) d=23.

5) e=4.

Since (d+e) exceeds 9, let us calculate (d+e-9) =18. So, in 2016, Orthodox Christian Easter falls on April 18 of the Julian calendar, which corresponds to May 1 in the Gregorian calendar.

The Julian period and calendar

Historians and annalists often deal with calendar calculations which involve various types of dates. To simplify the process for converting dates from one calendar to another, the “system of Julian days” or “continuous day count” was introduced. In 1583, the French scholar Joseph Justus Scaliger (1540 — 1609) came up with the idea of the so-called “Julian period”. He named this method of calculation in honor of his father Julius Caesar Scaliger (1484 — 1558), the famous humanist and scholar.

Joseph Scaliger suggested a chronological scale against which any historical date could be aligned. The starting point for counting the “Julian days” (JDN=0) was set to January 1, 4713 BNE, which was the era “from the foundation of the world” according to Scaliger. Then, the JDN value would increase by one every day. So, January 2, 4713 BNE equals to JDN=1 and so on. For example, January 1 of the 1st year NE is JDN=1721424.

In 1849, John Herschel (1792 — 1871) suggested expressing all the dates though the JD value, which is the number of days that passed since the beginning of the Scaliger cycle. The difference between the Julian date (JD) and the Julian day number (JDN) is that the former contains a fractional part which indicates the time of 24-hour day. It was agreed that the beginning of the Julian day would be noontime according to Greenwich Mean Time. So, the midnight of January 1 of the 1st year NE corresponds to JD=1721423.5. Note that the JD=1721424 will accumulate only by the noon of the specified day, because the count was started at noon January 1, 4713 BNE (the “zero point”). To make our calculations easier, we will use the rounded value of the Julian date or the Julian day number (JDN).

The procedure for calculating the Julian day number (JDN) for a specific Julian calendar date is as follows:

1) a= [(14-month) /12].

2) y=year+4800-a.

3) m=month+12a-3.

4) Julian day number:

JDN=day+ [(153m+2) /5] +365y+ [y/4] -32083.

Where “year” is the year of NE; “month” is the number of the month; “day” is the day of the month; value in brackets is the integer part.

Knowing the JDN, you can find the day of the week by calculating the remainder of the division of JDN by 7. Based on the remainder value, the days of the week are distributed as follows: 0 — Monday, 1 — Tuesday, 2 — Wednesday, 3 — Thursday, 4 — Friday, 5 — Saturday, 6 — Sunday.

For example, let us calculate the Julian day number for the Jewish Passover in 2016 (April 10 in the Julian calendar):

1) a=0.

2) y=6816.

3) m=1.

4) JDN=2457502.

Remainder of division (JDN mod 7) =5, therefore, it is Saturday.

Finding dates based on the Julian days

The method of calculation based on the Julian days can be useful, for example, for finding the date for Tisri 1. We don’t know the interval between Nisan 15 and Tisri 1 within one year. But the interval between Tisri 1 of the year to be found and Nisan 15 of the previous year is always 163 days because Nisan, Iyyar, Siwan, Tammuz, Ab, and Elul have an unchanging number of days. If you know the Julian day number for Nisan 15, you can, by adding 163, find the Julian day number for Tisri 1 of the following year.

For example, based on the Gauss formulas, Nisan 15 of the year 5775 in the Jewish calendar corresponds to March 22, 2015, in the Julian calendar. Now we can calculate JDN for this date (JDN =2457117). Consequently, Tisri 1 of the year 5776 corresponds to JDN=2457280. The remainder of division is 0. Therefore, the day is Monday. We have already determined that Nisan 15 of the year 5776 in the Jewish calendar (2016 NE) falls on Saturday. Using Table 3 (see above), we see that the year 5776 of the Jewish calendar is embolismic, that is, its duration is 385 days (an excessive year).

The procedure for converting a Julian day number (JDN) into a Julian calendar date is as follows:

1) c=JDN+32082.

2) d= [(4c+3) /1461].

3) e=c- [1461d/4].

4) m= [(5e+2) /153].

5) day=e- [(153m+2) /5] +1.

6) month=m+3—12* [m/10].

7) year=d-4800+ [m/10].

Where year is the year of NE; month is the number of the month; day is the day of the month; value in brackets is the integer part.

For example, let us convert the Julian day number JDN=2457280 (Tisri 1 of the year 5776 in the Jewish calendar) into a Julian calendar date:

1) c=2489362.

2) d=6815.

3) e=184.

4) m=6.

5) day=1.

6) month=9.

7) year=2015.

Consequently, Tisri 1 of the year 5776 in the Jewish calendar falls on September 1 2015 of the Julian calendar, or September 14 of the Gregorian calendar.

The Julian day and the Egyptian calendar

To convert a Jewish calendar date into a Julian calendar date, we should first find the the Julian day number:

JDN= (N-1) *365+ (M-1) *30+ (D-1) +1448638,

where “N” is the year of the Nabonassar era; “M” is the ordinal number of the Egyptian calendar month; “D” is the date of the month.

The calculation procedure of date is the same as the one described in the previous chapter.

Для For example, let us calculate the day of the Julian calendar corresponding to Pharmuthi 25 of the year 777 of the Nabonassar era.

Julian day number:

JDN= (777—1) *365+ (8—1) *30+ (25—1) +1448638=1732112.

Julian calendar date:

1) c=1764194.

2) d=4830.

3) e=37.

4) m=1.

5) day=7.

6) month=4.

7) year=30.

So, Pharmuthi 25 of the year 777 of the Nabonassar era falls on April 7th 30 NE.

Calculations simplified

Chronology calculations became so much easier now that we have computers. The above algorithms can be effectively implemented using popular computational programs or programming language scripts. Also, there are ready-to-use programs and online services designed specifically for calendar calculations; some of them are described in the Addendum.

Section 2. The Old Testament chronology

Speaking of the challenges of calculating dates in the era “from the foundation of the world”, or “from Adam” in Section 1, we didn’t mention one important reason for the lack of consensus regarding the biblical chronology. There are several versions of the Old Testament text (Jewish-Masoretic, Samaritan, Septuagint). For the most part, they are identical, but there are discrepancies which may affect chronology. Some passages contain significant chronological inconsistencies, so a natural question arises as to which dating is more accurate.

Eastern Orthodox Church regards the Septuagint as the canonical text of the Old Testament (The Septuagint comes from Latin “Interpretatio septuaginta seniorum” — “The translation of the seventy scholars”, for this reason, it is often referred to as LXX). The Septuagint is the translation of the Jewish Scripture into Greek completed at the initiative of Demetrius of Phalerum (350 — 283 BNE), the founder and head of the Library of Alexandria. Demetrius persuaded the Egyptian king Ptolemy II Philadelphus (308 — 245 BNE) to have the sacred books of the Jewish canon translated into Greek. Torah (the Pentateuch) was translated in the 3rd century BNE. The remaining Old Testament books were translated later — in the second and first centuries BNE. Some details regarding the process of translation for the Pentateuch are provided in the “Letter of Aristeas, the bodyguard of Philadelphus, to brother Philocrates”. This letter is cited, for example, by Philo of Alexandria (The Life of Moses, 2,6—7), by Josephus Flavius (Judean Antiquities, 12,1—2), in the Talmud (Megillah, 9), by Clement of Alexandria (Stromata, 1,22), by Irenaeus of Lyons (Against Heresies, 3,21,2), by Cyril of Jerusalem (Catechetical Lextures and Mystagogic Catecheses, 4.34), by Epiphanius of Cyprus (On the Seventy Interpreters), by Augustine the Blessed (The City of God, 18,42).

Below are listed some basic of the arguments in favor of the higher degree of accuracy of the Septuagint:

1) The translation of the Old Testament (Tanakh) into Greek, known as Septuagint, was completed in 3rd-1st centuries BNE and was based on the authentic Jewish text provided by the Jewish high priest. This is a sufficient warranty of the accuracy of the resulting text. One can argue about the nuances of meaning in the translated text, but it is hardly possible to assume that the dates and numbers could have been mistranslated.

2) The translators of the Septuagint were highly educated Jewish scribes. Those seventy two men continued to interact with each other as they were working on the Pentateuch (each Semitic tribe was represented by 6 scribes). One and the same passage was translated by different groups of scribes; then, the results were compared against each other. Thanks to this procedure, the probability of mistakes is very low.

3) The Septuagint was not created just for the Library of Alexandria. The Greek text was distributed far and wide. One copy was always at the disposal of the Jewish high priest:

“After he had arrived in Jerusalem, he [Egyptian king Ptolemy IV Philopator (c. 242 — 203 BNE)] offered sacrifice to the supreme God and made thank offerings and did what was fitting for the holy place. Then, upon entering the place and being impressed by its excellence and its beauty, he marveled at the good order of the temple, and conceived a desire to enter the sanctuary. When they said that this was not permitted, because not even members of their own nation were allowed to enter, not even all of the priests, but only the high priest who was pre-eminent over all — and he only once a year — the king was by no means persuaded. Even after the law had been read to him, he did not cease to maintain that he ought to enter, saying, ‘Even if those men are deprived of this honor, I ought not to be.’ And he inquired why, when he entered every other temple, no one there had stopped him” (3 Macc 1:9—12).

4) The Apostles and early Church Fathers quoted predominantly from the Greek text of the Old Testament. Luke, for example, follows the Septuagint (Gen 10:24; 11:12—13) when he gives his genealogy of Jesus by inserting Cainan (Lk 3:36) between Sala and Arphaxad. In the Masoretic text, Cainan is omitted.

5) From antiquity to the present day, the text of the Septuagint has been preserved almost intact, at least with regard to chronology.

6) The idea that the Jewish-Masoretic Tanakh is an infallible text of the original Old Testament is, obviously, erroneous. There’s enough evidence to the fact that the Jews had several versions of Tanakh with varying chronological data. For example, in the account from Adam through Noah, the Samaritan-Israelite Pentateuch is closer to the Jewish-Masoretic Tanakh, whereas in the partition from Arphaxad through Abraham it is closer to the chronology given in the Septuagint. This indicates an evolutionary accumulation of discrepancies over a long period of time.

7) Accumulation of errors in the Tanakh continued throughout the1st century NE. The Jewish historian Josephus Flavius in his famous book provides the chronological data in the Bible which contains further discrepancies (see Judean Antiquities).

8) The belief in the infallibility of the Jewish-Masoretic Tanakh faded away altogether after the ancient Jewish manuscripts of Qumran had been unearthed in 1947. These manuscripts reflect a whole range of chronological and textual traditions. Based on the paleographic data, external evidence, and the radiocarbon analysis, the main body of these manuscripts date between 250 BNE to 68 NE.

9) The finalization of chronology in the Jewish Tanakh occurred, most likely, around the 2nd century NE. This process must have been caused by historical circumstances, such as the destruction of the Jewish Temple, and the Roman invasion of Judea in 70 NE. Scattered throughout the world, the Jews must have been motivated to start thinking about preserving the uniformity of their religious texts. The fixed Jewish-Masoretic text of Tanakh was first translated into a foreign language in Syria at the end of the 2nd century NE. This translation was later called Peshitta. After some time, in the 4th century NE, the Jewish-Masoretic Tanakh was translated by into Latin by Jerome of Stridon; this translation was termed the Vulgate.

10) The fixed text of the Jewish-Masoretic Tanakh is not identical across various manuscripts and contains multiple discrepancies.

11) The much shorter chronology of the Jewish Tanakh contradicts the current data obtained through independent dating methods. For example, according to the Jewish tradition, the conquest of the Babylonian Empire by Cyrus II happened in 370 BNE (year 3390 from the foundation of the world in the Jewish calendar). But the scientific dating places this event in 539 BNE.

Based on the above considerations, it seems reasonable to use the dates and numbers of the Septuagint as the source for recreating the Old Testament chronology.

The brief research given below is not meant to demonstrate the whole range of the Old Testament datings. Its main purpose is to indicate the general duration of the described events. That’s why only key dates have been included. Let us first note that the period from the creation of the world to the beginning of the new era was 5550 years. So for the sake of convenience, the calculated dates are given in a twofold format: first, the dates from Adam, then the astronomical dates in NE (in parentheses; -5549 NE corresponds to 5550 BNE and so on).

1 (-5549). Creation of Adam and Eve

“So God created man in his own image, in the image of God created he him; male and female created he them… And the evening and the morning were the sixth day” (Gen 1:27, 31; compare Gen 2:7—25).

“And Adam called his wife’s name Eve; because she was the mother of all living” (Gen 3:20).

The tradition holds that the first man and woman, Adam and Eve, were created on the sixth days of the 1st year. It is believed that this day was Friday.

231 (-5319). The birth of Seth

“And Adam lived an 230 years, and begat a son in his own likeness, after his image; and called his name Seth” (Gen 5:3).

1+230=231

436 (-5114). The birth of Enos

“And Seth lived an 205 years, and begat Enos” (Gen 5:6).

231+205=436

626 (-4924). The birth of Cainan

“And Enos lived 190 years, and begat Cainan” (Gen 5:9).

436+190=626

796 (-4754). The birth of Mahalaleel

“And Cainan lived 170 years, and begat Mahalaleel” (Gen 5:12).

626+170=796

961 (-4589). The birth of Jared

“And Mahalaleel lived 165 years, and begat Jared” (Gen 5:15).

796+165=961

1123 (-4427). The birth of Enoch

“And Jared lived an 162 years, and he begat Enoch” (Gen 5:18).

961+162=1123

1288 (-4262). The birth of Methuselah

“And Enoch lived 165 years, and begat Methuselah” (Gen 5:21).

1123+165=1288

1475 (-4075). The birth of Lamech

“And Methuselah lived an 187 years, and begat Lamech” (Gen 5:25).

1288+187=1475

1663 (-3887). The birth of Noah

“And Lamech lived an 188 years, and begat a son: And he called his name Noah” (Gen 5:28—29).

1475+188=1663

2163 (-3387). The birth of Sim, Ham, and Japheth

“And Noah was 500 years old: and Noah begat Shem, Ham, and Japheth” (Gen 5:32).

1663+500=2163

2263 (-3287). The Great Flood

“And Noah was 600 years old when the flood of waters was upon the earth” (Gen 7:6).

The Flood happened 100 years after the birth of Sim, Ham and Japheth.

2163+100=2263

2265 (-3285). The birth of Arphaxad

“Shem was an hundred <and two> years old, and begat Arphaxad 2 years after the flood” (Gen 11:10).

The conjecture <and two> eliminates the contradiction between Gen 5:32, Gen 7:6 and Gen 11:10. This numeral was probably lost in the process of copying the manuscript long before the Septuagint was created. It is also absent in the Jewish-Masoretic Torah.

2263+2=2265

2400 (-3150). The birth of Cainan

“And Arphaxad lived 135 years, and begat Cainan” (Gen 11:12).

2265+135=2400

2530 (-3020). The birth of Salah [Sala]

“And Cainan lived 130 years, and begat Salah” (Gen 11:12).

2400+130=2530

2660 (-2890). The birth of Eber

“And Salah lived 130 years, and begat Eber” (Gen 11:14).

2530+130=2660

2794 (-2756). The birth of Peleg

“And Eber lived 134 years, and begat Peleg” (Gen 11:16).

2660+134=2794

2924 (-2626). The birth of Reu

“And Peleg lived 130 years, and begat Reu” (Gen 11:18).

2794+130=2924

3056 (-2494). The birth of Serug

“And Reu lived 132 years, and begat Serug” (Gen 11:20).

2924+132=3056

3186 (-2364). The birth of Nahor

“And Serug lived 130 years, and begat Nahor” (Gen 11:22).

3056+130=3186

3265 (-2285). The birth of Terah

“And Nahor lived 79 years, and begat Terah” (Gen 11:24).

3186+79=3265

3335 (-2215). The birth of Abram, Nahor, and Haran

“And Terah lived 70 years, and begat Abram, Nahor, and Haran” (Gen 11:26).

3265+70=3335

3435 (-2115). The birth of Isaac

“And Abraham was an 100 years old, when his son Isaac was born unto him” (Gen 21:5).

3335+100=3435

3495 (-2055). The birth of Esau and Jacob

“And Isaac was 60 years old when she [Rebekah] bare them [Esau and Jacob]” (Gen 25:26).

3435+60=3495

3625 (-1925). The Jews move to Egypt

“And Pharaoh said unto Jacob, How old art thou? And Jacob said unto Pharaoh, The days of the years of my pilgrimage are an 130 years” (Gen 47:8—9).

3495+130=3625

4055 (-1495). The Exodus from Egypt

“Now the sojourning of the children of Israel, who dwelt in Egypt <and in the land of Canaan>, was 430 years” (Ex 12:40).

Some translations contain the conjecture <and in the land of Canaan>, perhaps wishing to avoid the contradiction with the prophecy: “And he said unto Abram, Know of a surety that thy seed shall be a stranger in a land that is not theirs, and shall serve them; and they shall afflict them 400 years” (Gen 15:13). Actually, this correction in not necessary in Ex 12:40. It’s reasonable to assume that the first 30 years in Egypt there was no oppression for the Jews. The remaining 400 years, however, were spent in slavery. There’s a certain logic to this. After his arrival in Egypt, Abraham came into the presence Pharaoh and was received with honor: “And Pharaoh commanded his men concerning him: and they sent him away, and his wife, and all that he had” (Gen 12:20). He was a rich man: “And Abram was very rich in cattle, in silver, and in gold” (Gen 13:2). The Bible clearly indicates that Abraham was a slave owner, not a slave: “And he entreated Abram well for her sake: and he had sheep, and oxen, and he asses, and menservants, and maidservants, and she asses, and camels” (Gen 12:16).

However, the conjecture <and in the land of Canaan> is not just superfluous but also erroneous because the Jews spent in Canaan more than 30 years. Let’s do the math. Abraham arrived in Canaan when he was 75 years old (see Gen 12:1—5), and, according to the chronology, it was the year 3410 since the foundation of the world, or 215 years before their settlement in Egypt. So, if you make Canaan the starting point for the 430 years, there would be only 215 years left in the Egyptian period, not 400. And there are no indications that Jews were slaves in Canaan. So you see that the conjecture is not helpful. Therefore, it is more reasonable to view the 430 years as the total time spent by the Jews in Egypt.

3625+430=4055

4532 (-1018). The beginning of Solomon’s reign

“And it came to pass in the 480 year after the children of Israel were come out of the land of Egypt, in the 4 year of Solomon’s reign over Israel, in the month Zif, which is the second month, that he began to build the house of the LORD” (1 Kings 6:1).

There were 477 years between Exodus and the reign of Solomon.

4055+477=4532

4535 (-1015). The founding of the first Temple in Jerusalem

The construction of the Temple began 3 full years after, that is, in the fourth year of Solomon’s reign (see 1 Kings 6:1).

4532+3=4535

4572 (-978). The beginning of Rehoboam’s reign

“And the time that Solomon reigned in Jerusalem over all Israel was 40 years. And Solomon slept with his fathers, and was buried in the city of David his father: and Rehoboam his son reigned in his stead” (1 Kings 11:42—43).

37 years after the construction of the Temple began.

4535+37=4572

4589 (-961). The beginning of Abijam’s [Abijah’s] reign

“And Rehoboam the son of Solomon reigned in Judah. Rehoboam was forty and one years old when he began to reign, and he reigned 17 years in Jerusalem” (1 Kings 14:21).

“And Rehoboam slept with his fathers, and was buried with his fathers in the city of David. And his mother’s name was Naamah an Ammonitess. And Abijam his son reigned in his stead” (1 Kings 14:31).

4572+17=4589

4592 (-958). The beginning of Asa’s reign

“3 years reigned he [Abijam] in Jerusalem” (1 Kings 15:2).

“And Abijam slept with his fathers; and they buried him in the city of David: and Asa his son reigned in his stead” (1 Kings 15:8).

4589+3=4592

4633 (-917). The beginning of Jehoshaphat’s reign

“And 41 years reigned he [Asa] in Jerusalem” (1 Kings 15:10).

“And Asa slept with his fathers, and was buried with his fathers in the city of David his father: and Jehoshaphat his son reigned in his stead” (1 Kings 15:24).

4592+41=4633

4658 (-892). The beginning of Jehoram’s [Joram’s] reign

“And he [Jehoshaphat] reigned 25 years in Jerusalem” (1 Kings 22:42).

“And Jehoshaphat slept with his fathers, and was buried with his fathers in the city of David his father: and Jehoram his son reigned in his stead” (1 Kings 22:50).

4633+25=4658

4666 (-884). The beginning of Ahaziah’s reign

“And he [Jehoram] reigned 8 years in Jerusalem” (2 Kings 8:17).

“And Joram slept with his fathers, and was buried with his fathers in the city of David: and Ahaziah his son reigned in his stead” (2 Kings 8:24).

4658+8=4666

4667 (-883). The beginning of Athaliah’s [Hotholia’s] reign

“And he [Ahaziah] reigned 1 year in Jerusalem” (2 Kings 8:26).

“And when Athaliah the mother of Ahaziah saw that her son was dead, she arose and destroyed all the seed royal. But Jehosheba, the daughter of king Joram, sister of Ahaziah, took Joash the son of Ahaziah, and stole him from among the king’s sons which were slain; and they hid him, even him and his nurse, in the bedchamber from Athaliah, so that he was not slain. And he was with her hid in the house of the LORD six years. And Athaliah did reign over the land” (2 Kings 11:1—3).

4666+1=4667

4673 (-877). The beginning of Jehoash’s [Joash’s] reign

“And the seventh year Jehoiada sent and fetched the rulers over hundreds, with the captains and the guard, and brought them to him into the house of the LORD, and made a covenant with them, and took an oath of them in the house of the LORD, and shewed them the king’s son [Jehoash]” (2 Kings 11:4).

“And they slew Athaliah with the sword beside the king’s house. Seven years old was Jehoash when he began to reign” (2 Kings 11:20—21).

Jehoash began reigning after six full years, on the seventh year of Athaliah’s reign.

4667+6=4673

4713 (-837). The beginning of Amaziah’s [Amasia’s] reign

“And 40 years reigned he [Jehoash] in Jerusalem” (2 Kings 12:1).

“And he [Jehoash] died; and they buried him with his fathers in the city of David: and Amaziah his son reigned in his stead” (2 Kings 12:21).

4673+40=4713

4742 (-808). The beginning of Azariah’s reign

“He [Amaziah] was twenty and five years old when he began to reign, and reigned 29 years in Jerusalem” (2 Kings 14:2).

“And all the people of Judah took Azariah, which was sixteen years old, and made him king instead of his father Amaziah” (2 Kings 14:21).

4713+29=4742

4794 (-756). The beginning of Jotham’s reign

“And he [Azariah] reigned 52 years in Jerusalem” (2 Kings 15:2).

“So Azariah slept with his fathers; and they buried him with his fathers in the city of David: and Jotham his son reigned in his stead” (2 Kings 15:7).

4742+52=4794

4810 (-740). The beginning of Ahaz’s reign

“And he [Jotham] reigned 16 years in Jerusalem” (2 Kings 15:33).

“And Jotham slept with his fathers, and was buried with his fathers in the city of David his father: and Ahaz his son reigned in his stead” (2 Kings 15:38).

4794+16=4810

4826 (-724). The beginning of Hezekiah’s reign

“And [Ahaz] reigned 16 years in Jerusalem” (2 Kings 16:2).

“And Ahaz slept with his fathers, and was buried with his fathers in the city of David: and Hezekiah his son reigned in his stead” (2 Kings 16:20).

4810+16=4826

4855 (-695). The beginning of Manasseh’s reign

“And he [Hezekiah] reigned 29 years in Jerusalem” (2 Kings 18:2).

“And Hezekiah slept with his fathers: and Manasseh his son reigned in his stead” (2 Kings 20:21).

4826+29=4855

4910 (-640). The beginning of Amon’s [Ammon’s] reign

“Manasseh was twelve years old when he began to reign, and reigned fifty <and five> years in Jerusalem” (2 Kings 21:1).

“And he [Manasseh] reigned 55 years in Jerusalem” (2 Chron 33:1).

“And Manasseh slept with his fathers, and was buried in the garden of his own house, in the garden of Uzza: and Amon his son reigned in his stead” (2 Kings 21:18).

The conjecture <and five> here helps to remove inconsistency between 2 Kings 21:1 и 2 Chron 33:1. This numeral was probably lost in the process of copying the manuscript long before the Septuagint was created. It is also absent in the Jewish-Masoretic Torah.

4855+55=4910

4912 (-638). The beginning of Josiah’s reign

“And he [Amon] reigned 2 years in Jerusalem” (2 Kings 21:19).

“And he [Amon] was buried in his sepulchre in the garden of Uzza: and Josiah his son reigned in his stead” (2 Kings 21:26).

4910+2=4912

4943 (-607). The battle of Megiddo, the reign of Jehoahaz, captivity in Egypt, the beginning of the reign of Jehoiakim

“And he [Josiah] reigned 31 years in Jerusalem” (2 Kings 22:1).

“In his days Pharaohnechoh king of Egypt went up against the king of Assyria to the river Euphrates: and king Josiah went against him; and he slew him at Megiddo, when he had seen him. And his servants carried him in a chariot dead from Megiddo, and brought him to Jerusalem, and buried him in his own sepulchre. And the people of the land took Jehoahaz the son of Josiah, and anointed him, and made him king in his father’s stead” (2 Kings 23:29—30).

“And he [Jehoahaz] reigned 3 months in Jerusalem” (2 Kings 23:31).

“And Pharaohnechoh made Eliakim the son of Josiah king in the room of Josiah his father, and turned his name to Jehoiakim, and took Jehoahaz away: and he came to Egypt, and died there” (2 Kings 23:34).

4912+31=4943

4954 (-596). The reign of Jehoiachin [Jeconiah], the Babylonian captivity, the beginning of the reign of Zedekiah

“And he [Jehoiakim] reigned 11 years in Jerusalem” (2 Kings 23:36).

“So Jehoiakim slept with his fathers: and Jehoiachin his son reigned in his stead” (2 Kings 24:6).

“And he [Jehoiachin] reigned in Jerusalem 3 months” (2 Kings 24:8).

“And he [Nebuchadnezzar] carried away Jehoiachin to Babylon, and the king’s mother, and the king’s wives, and his officers, and the mighty of the land, those carried he into captivity from Jerusalem to Babylon” (2 Kings 24:15).

“And the king of Babylon made Mattaniah his [Jehoiachin] father’s brother king in his stead, and changed his name to Zedekiah” (2 Kings 24:17).

4943+11=4954

4965 (-585). Judea is enslaved by Babylon

“And he [Zedekiah] reigned 11 years in Jerusalem” (2 Kings 24:18).

“So they took the king, and brought him up to the king of Babylon to Riblah; and they gave judgment upon him. And they slew the sons of Zedekiah before his eyes, and put out the eyes of Zedekiah, and bound him with fetters of brass, and carried him to Babylon. And in the fifth month, on the seventh day of the month, which is the nineteenth year of king Nebuchadnezzar king of Babylon, came Nebuzaradan, captain of the guard, a servant of the king of Babylon, unto Jerusalem: And he burnt the house of the LORD, and the king’s house, and all the houses of Jerusalem, and every great man’s house burnt he with fire. And all the army of the Chaldees, that were with the captain of the guard, brake down the walls of Jerusalem round about. Now the rest of the people that were left in the city, and the fugitives that fell away to the king of Babylon, with the remnant of the multitude, did Nebuzaradan the captain of the guard carry away” (2 Kings 25:6—11).

Modern science dates the conquest of Jerusalem by the Babylonian king Nebuchadnezzar II (c. 634 — 562 BNE) to 586 BNE.

4954+11=4965

5012 (-538). The conquest of Babylon by Cyrus II, the end of the Babylonian captivity of the Jews

“And they burnt the house of God, and brake down the wall of Jerusalem, and burnt all the palaces thereof with fire, and destroyed all the goodly vessels thereof. And them that had escaped from the sword carried he away to Babylon; where they were servants to him and his sons until the reign of the kingdom of Persia: To fulfil the word of the LORD by the mouth of Jeremiah, until the land had enjoyed her sabbaths: for as long as she lay desolate she kept sabbath, to fulfil 70 years” (2 Chron 36:19—21; compare Jer 25:11—12; Jer 29:10; Dan 9:2; Zech 1:12; Zech 7:4—5).

Modern science dates the conquest of Babylon by the Persian king Cyrus II (c. 593 — 530 BNE) to 539 BNE. As you may have noticed, the beginning of the seventy-year devastation of Judah falls on the date of the battle of Megiddo, 608 BNE. Three major captivities were experienced by the Jews in this period. The first was the exile inflicted at the hands of the Egyptian pharaoh Necho II in 608 BNE. The second one happened in 597 BNE, and the third one was in 586 BNE. The last two times they were captured by the Babylonian king Nebuchadnezzar II. Obviously, the 70-year-long period of the devastation of Judah is divided up into 11 years in Egypt and 59 years in Babylon.

4965+ (586—539) =5012

It is also important to note that 5550 years between the foundation of the world and the start of the new era is an approximate number. Taking into account the number of time intervals which make up the whole duration, as well as their number rounded to the accuracy of one year, the resulting error can roughly be estimated as plus or minus 50 years.

Modern-day scientists will, probably, disagree with dating the age the Earth as several thousand years. They will, most likely, cite scientific arguments in favor of the much older Solar system and Universe. It would be worth discussing this question separately, but it would probably require another book. At this time, let us limit ourselves to the information that we have from the Bible.

Section 3. Versions of the Gospel chronology

Christian sources on the life of Jesus Christ

The main sources of information on the life of Jesus Christ are the canonical Gospels written by the apostles Matthew, Mark, Luke and John.

The Gospel of Matthew was written about the third quarter of the 1st century. Tradition holds that it was written by Levi Matthew, the son of Alphaeus, one of the Twelve (see Mt 9:9; Mk 2:14; Lk 5:27). Originally it was written in the old Hebrew, but later it was translated into Greek and became widely accepted.

“So, Matthew wrote the Gospel for the Jews in their own language, while Peter and Paul were preaching in Rome and founded the Church” (Irenaeus of Lyons. Against Heresies, 3,1,1; compare Eusebius of Caesarea. Church History, 5,8).

“Initially Matthew preached the Gospel to the Jews; but then he took it to other nations, though it was written in his own tongue. When summoned to go elsewhere, he left them with his Scripture” (Eusebius of Caesarea. Church History, 3,24,6).

“Matthew the Apostle, who was also called Levi, used to be a tax-collector; he complied the Gospel of Jesus Christ for the sake of spiritual cleansing of believers. At first, it was published in Judea in Hebrew, but later someone translated it into Greek [compare Eusebius of Caesarea, Church History, 3,39,16]. The Hebrew version survived to the present day [around the beginning of the 5th century] in the Library of Caesarea [Caesarea of Palestine], so arduously created and maintained by Pamphilus [of Caesarea]. I also had the opportunity to get the book described for me by the Nazarene from the Syrian town of Berea who had been using it. It must be noted that this Gospel-writer, in quoting the Old Testament testimonies, whether himself or on behalf of our Lord and Savior, always follows the Hebrew text of the Covenant, not the authority of the translators of the Septuagint. Therefore, there are the following two versions: ‘Out of Egypt I have called my son’ [Mt 2:15; Hos 11:1] and: ‘He will be called a Nazorean’ [Mt 2:23; Is 11:1 <heb. ‘NZR’ = Nazorean, a sprout, a root>; compare Num 6:21; Judg 13:5; 1 Sam 1:11; Am 2:11—12]” (Jerome of Stridon. On Famous Men, 3).

The Gospel of Mark was written around the middle of the 1st century. According to the tradition, it was written by John Mark (see Act 12:12), the nephew of Barnabas (see Col 4:10), who was one of the seventy apostles and a co-worker of Peter (see 1 Pet 5:13). It is regarded as the earliest of the four Gospels. It is the shortest of them all, and it was used as a source for writing the Gospels of Matthew and Luke.

“These are the words of the presbyter [Papias of Hierapolis]: ‘Mark was the interpreter of Peter; he accurately recorded everything that the Lord had said and done, but not in order, for he himself did not hear the Lord speak, neither did he walk with Him. Later he accompanied Peter who taught as he saw fit based on the circumstances, and did not necessarily relate the words of Christ in order. In recording everything the way he remembered it, Mark did not err against the truth. His only concern was not to miss or misrepresent anything.’ That is what Papias said concerning Mark” (Eusebius of Caesarea. Church History, 3,39,15—16).

“Peter and Paul preached in Rome and founded a church there. After their departure, Mark, Peter’s disciple and interpreter, passed down to us in writing everything that Peter had taught” (Irenaeus of Lyons. Against Heresies, 3,1,1; compare Eusebius of Caesarea. Church History, 5,8).

“Mark, the disciple and the interpreter of Peter, wrote a short Gospel at the request of the fellowship in Rome, having recorded everything that he had heard from Peter. Clement [of Alexandria] in the sixth book of his ‘Brief Explanations’, as well as Papias, the bishop of Hierapolis, both testify that Peter approved of this work and declared that this Gospel should be read in all the churches. Peter also mentions Mark in his first epistle, metaphorically calling Rome Babylon: ‘The church that is at Babylon, elected together with you, saluteth you; and so doth Marcus my son’ [1 Pet 5:13]. Availing himself of the Gospel that he himself had compiled, Mark departed to Egypt, and, preaching Christianity in Alexandria, founded a church there, which became famous through its sound teaching and godliness, and was known for instructing all its adepts to follow the example of Christ. The highly-educated Jew by the name of Philo, witnessing the first church of Alexandria which was still Jewish by status, wrote a book about their way of life, confirming, according to Luke, that they had much in common with Jerusalem. Mark died in the eighth year of Nero’s reign [61/62 NE] and was buried in Alexandria. He was replaced by Annian” (Jerome of Stridon. On Famous Men, 8).

The Gospel of Luke was written around the third quarter of the 1st century. According to the tradition, it was written by Luke, the doctor, one of the Seventy and a co-laborer of Paul (see Col 4:14; Phm 1:24; 2 Tim 4:10).

“So, Luke, the co-laborer of Paul, wrote down in the form a book the Gospel which he preached” (Irenaeus of Lyons. Against Heresies, 3,1,1; compare Eusebius of Caesarea. Church History, 5,8).

“As one can gather from his writings, Luke, the doctor from Antioch, was very knowledgeable in the Greek language. The author of the Gospel and Paul’s follower, he accompanied the apostle in all his journeys. Here is what Paul said of him: “And we have sent with him the brother, whose praise is in the gospel throughout all the churches (Corinthians) [2 Cor 8:18]; “Luke, the beloved physician, and Demas greet you” (Colossians) [Col 4:14], “Only Luke is with me” (Timothy) [2 Tim 4:10]. The other excellent work written by Luke, “Acts of the Apostles”, covers events during Paul’s second year in Rome, which was the fourth year of Nero’s reign [57/58 NE]. On this basis we conclude that this book was written in this city… Some believe that when Paul says in his epistle: “according to my gospel, [Rom 2:16], he refers to the book of Luke [the Greek for Gospel is “Good News)], and that Luke knew the stories of the Gospel not only from Paul who didn’t see the Lord in the flesh, but also from other apostles. He mentions it in the beginning of his work: “…Even as they delivered them unto us, which from the beginning were eyewitnesses, and ministers of the word.” [Lk 1:2]. So, he wrote the Gospel on the basis of what he had heard from others, while “Acts of the Apostles” was written out of his own experience” (Jerome of Stridon. On Famous Men, 7).

The Gospel of John was written by the end of the 1st century. Tradition holds that it was compiled by John the Theologian, the son of Zebedee (see Mt 10:2; Mk 3:17; Lk 6:14; Jn 21:2, 24).

“Then, John, the disciple of Jesus who lay on His bosom [Jn 13:23], also published his Gospel during his time in Ephesus in Asia” (Irenaeus of Lyons. Against Heresies, 3,1,1; compare Eusebius of Caesarea. Church History, 5,8).

“John, the apostle, the one especially loved by Jesus [Jn 21:20, 24], the son of Zebedee and the brother of Jacob who was beheaded by Herod after the sufferings of the Lord, last of all wrote his Gospel at the request of some bishops in Asia who contended against Cerinthus and other heretics, especially the teachings of Ebionites who taught that Christ didn’t exist before Mary. So, John was asked to speak in defense of the doctrine of Divine Birth. There was yet another reason: having read the works of Matthew, Mark, and Luke, John approved of their narratives and confirmed that they contained the truth, noting that these narratives only describe was happened during the one year after John [the Baptist] was put in prison and executed. So, he himself wrote about a period preceding John’s imprisonment, and it can be a revelation for those who diligently read the works of the Gospel-writers. In addition, this consideration removes the contradictions that seemed to exist between the text of John and others… On the fourteenth year after Nero [82 NE] Domitian began the second persecution against Christians. John was exiled to the island of Patmos and wrote there the Apocalypse, which was later commented on by Justin Martyr and Irenaeus. But after Domitian’s death [96 NE] and the abolition of his cruel decrees, John returned to the city of Ephesus and, remaining there until the arrival of the emperor Trajan, contributed in every way to the planting of churches throughout Asia. Died of old age in the 68th year after the Passion of the Lord and was buried near Ephesus” (Jerome of Stridon. On Famous Men, 7; compare Eusebius of Caesarea. Church History, 3,24,7—14).

So, out of the four canonical Gospels, two were written by the closest disciples of Jesus Christ, the apostles John and Matthew, who were eyewitnesses of the described events. The other two were written by Mark and Luke, the disciples of Jesus, who belonged to the Seventy and were called at a later time (see Lk 10:1—2). Nevertheless, they had been in close contact with the original Twelve. All of them related in their narratives not only what they could remember themselves, but also the accounts of those who lived near to the time of Jesus. So, the Gospel narratives are the firsthand and secondhand sources, which, by their very nature, are more accurate and have more credibility compared to any other sources of information.

In later chapter we will examine the exact information provided in the four canonical Gospels with regard to chronology.

In addition to the canonical Gospels, there is also a number of Apocryphal Gospels. They were not included in the Canon either because they contain a pious forgery or because of some heretical content. That is why it would be highly inadvisable to use them for the purposes of recreating biblical chronology.

Non-Christian sources on the life of Jesus Christ

Among the whole corpus of early non-Christian writings which shed light on the life of Jesus Christ, the following are particularly noteworthy.

Pliny the Younger (c. 61 — c. 113 NE), a Roman politician and writer, a lawyer. In a letter to the Emperor Trajan (reigned in 98 — 117 NE) he says:

“I consider it my sacred duty to seek your advice, sire, to find an answer to those questions that arouse my bewilderment. I’ve never witnessed trials against Christians. Therefore, I do not know what they are usually interrogated on and for what and to what extent they are punished. For I was in a great difficulty as to whether I should recognize the differences in their ages, or not at all distinguish minors from mature adults, whether I should grant pardon for repentance (or maybe renunciation of Christianity would not do any good to someone who was once a Christian), whether to execute them for the very name they bear [nomen ipsum] in the absence of any other crimes, or for the crimes [flagitia] having some connection with the name. Meanwhile, I acted in the following manner with those who, as I was informed, were Christians. I interrogated them on whether they were Christians and, when they confessed, I pressed my question the second and third time while threatening them with execution. Those who persisted I ordered to be executed [ducijussi]. I didn’t doubt that, regardless of the nature of wrongs they confessed, their stubbornness and impenitence alone deserved punishment. However, apart from those executed, there were others who were out of their minds as well. But because they were Roman citizens, I ordered that they be set apart to be sent to the capital. However, we had more and more complications as we proceeded. I received an anonymous report containing a list of Christians, but among them there were quite a few of those who denied that they were Christians and claimed they had never belonged to that group. When they, together with me, called upon the gods and worshiped your image which I had ordered to bring along with the statues of the gods, and when they cursed the name of Christ (they say, true Christians cannot be forced to do any of these three acts), I deemed it possible to release them. Others, whose names were on the list, confessed that they had been Christians at one time but left that fellowship, some three year ago, some earlier, and some even twenty years ago. All of them worshiped your image and the statues of the gods, having cursed the name of Christ. According to their own words, their whole crime consisted in that they gathered together early in the morning on certain days and sang hymns to Christ as God, and that in the name of religion [sacramento] they had bound themselves not to do any crimes, but to refrain from stealing, robbery, adultery, to keep promises and pay off debts, and that after their gatherings they got together again to take food, which was, incidentally, regular and innocent. And even this they stopped doing after I banned the hetaeria on your authority. Nevertheless, I judged it necessary to subject to torture the two slaves, who were called deaconesses [ministrae], in order to find out what is right and just there. But I found nothing except utter superstition of a gross kind. Therefore, postponing further proceedings, I appeal to you for advice” (Letter 10,96).

In terms of chronology, the above letter, testifies only to the relatively wide spread of Christianity by the beginning of the second century.

Gaius Suetonius Tranquill (c. 70 — c. 126 NE), Roman writer, historian, encyclopedist, and personal secretary of Emperor Hadrian. In his work “The Lives of the Twelve Caesars” [De vita Caesarum], he records the deeds of the Emperor Claudius (reigned in 41 — 54 NE):

“He [Claudius] expelled from Rome the Jews who were constantly stirred by Chresto” (Ibid., 5,25,4).

Some skeptical scholars, who see here the name of Chrest, are not inclined to associate it with Jesus. On the other hand, there’s nothing here that prevents us from assuming that this is a distorted name of Christus or Χριστός. Moreover, this is exactly what Tertullian points out: “The designation ‘Christian’, as follows from the etymology of the word, derives from the word ‘anointment’. And the name Chrestian, incorrectly pronounced by you [Romans] (because you do not even know exactly what we are called), means ‘pleasantness’ or ‘goodness’” (Apologeticum, 3,5). Lactantius makes a similar remark: “However, it is necessary to explain the meaning of this name [Christ] because some ignorant people, who would call him Chrest, make a mistake by mixing up the two sounds” (Divine Institutes, 4,7,5). Also, the Book of Acts says that when Paul came to Corinth, he found there the exiled Jews, “because that Claudius had commanded all Jews to depart from Rome” (Act 18:2). But what else, other than the spreading of the teaching of Jesus Christ, could cause the Roman Jews to be “constantly stirred”?

The stubbornness of skeptics in this matter is not so arbitrary as it is pointless, because Suetonius speaks more precisely in another place of “The Lives of the Twelve Caesars”, Suetonius, speaking of the deeds of the Emperor Nero (reigned in 54 — 68 NE): « [Nero] punished Christians [Christiani], the adherents of a new and pernicious superstition” (Ibid., 6,16,2). The reasons behind this persecution were explained by Tacitus, as will be mentioned later.

Speaking of chronology, Suetonius testifies to the wide spread of Christianity in the middle of the first century.

Cornelius Tacitus (c. 55 — c. 120 NE), the Roman writer, historian, forensic orator, senator. In his “Annales” he writes:

“And Nero, wishing to overcome the rumors [about his orders to set Rome on fire], found the scapegoats and gave over to the most excruciating tortures those who through their abominations had incurred general hatred of the populace and whom the crowd called Christians. This Christ, from whom this name is derived, was executed by the procurator Pontius Pilate under Tiberius. For a time this malicious superstition was suppressed but then broke out again, and not only in Judea where this blight originated, but also in Rome, where every abomination and every shameful thing in the world is gathered and where it finds ready adepts. So, at first, those who openly recognized themselves as belonging to this sect were seized, and then, using the information they provided, a great number of others were denounced, not so much as villainous arsonists but as haters of the human race in general. Their executions were accompanied by humiliations and insults, for they were clothed in the skins of wild animals so as to be torn apart by dogs; they were crucified on crosses, and, being sentenced to death by burning, set on fire at nightfall for illumination. Nero provided his gardens for this show. He also organized a performance in the circus where he sat among the crowds, clothed as a charioteer, or rode in a chariot as a participant in a contest. And although those Christians were guilty and deserved the severest of punishments, all these cruelties aroused compassion for them, for it seemed that they were being exterminated not for the sake of the common good, but simply because of Nero’s bloodthirstiness” (Ibid., 15,44).

Tacitus specifically mentions the execution of Jesus Christ as taking place at the time of the emperor Tiberius in Rome and Pontius Pilate in Judea. But this does not give us any more information apart from what we already know from the Gospels.

Josephus Flavius (c. 37 — c. 100) was the Jewish commander, writer, historian who served at the Roman court. He writes in his work “Judean Antiquities”:

“Having learned of the death of [Porcius] Festus, the emperor sent [Lucceius] Albinus as his procurator in Judea. About the same time, the king [Agrippa] stripped Joseph [Cavius] of his high-priesthood and appointed Ananus, the son of Ananus, as his successor. The latter, Ananus the Senior, was a very happy man: he had five sons who all became high priests after him, and he himself had occupied this honorable position for a very long time. None of our high priests had such a happy lot in life. Anan the Junior, of whose appointment we just spoke, was a harsh and impetuous man. He belonged to the party of the Sadducees, which, as we have already mentioned, was known in courts for their immoderate cruelty. Being a ruthless man, Anus considered the death of Festus and Albinus’s temporary absence to be a perfect time to satisfy his cruelty. So, calling together the Sanhedrin, he had them interrogate James [Jacob], the brother of Jesus, called Christ, as well as several others. They were accused of violating the laws and sentenced to death by stoning” (Ibid., 20,9,1).

Porcius Festus was a Roman governor in Judea between the years 59—62 NE at the time of Agrippa II, the tetrarch. Agrippa reigned between 48 — 93 NE, and his reign is associated with the trial of the apostle Paul in Caesarea (see Act 25—26). Anan the Senior is mentioned in the Gospels as High Priest Annas, Joseph Caiaphas’s father-in-law (see Lk 3:2; Jn 18:13, 24). The high-priesthood of Anan the Senior falls on years 6—15 NE, and the high-priesthood of Caiaphas between 18—37 NE. The sons of Anan (Annas) also became High Priests: Eleazar was the high priest in the years 16—17 NE (Judean Antiquities, 18,2,2), Jonathan in 37 NE (Ibid., 18,4,3; 18,5,3; 19,6,4), Theophilus in the years 37—41 NE (Ibid., 18,5,3; 19,6,2). [Could he be that very “Honorable [most excellent] Theophilus” to whom Luke addressed two of his books and who subsequently converted to Christianity? See Lk 1:3; Act 1:1], Matthias in 43 NE (Ibid., 19,6,4; 19,8,1), Anan the Junior in 63 NE (Ibid., 20,9,1). So, according to Josephus, James [Jacob], the stepbrother of Jesus, was executed in 63 NE. James, the brother of Jesus, is mentioned in the New Testament (see Mt 13:55; Mk 6:3; Act 12:17; 15:13; 21:18; Gal 1:18—19; 2:9). Also, Eusebius of Caesarea quotes Hegesippus, the second-century Christian writer, who says that James [Jacob] was thrown down from the roof of the Jerusalem temple and then stoned to death (see Church History, 2,23).

Elsewhere, Josephus writes:

“There lived around this time a wise man, Jesus <, if such a designation can be applied to him>. He was performing amazing deeds and became the Mentor for those who readily accepted the truth. He attracted many Jews and Greeks to himself. <That man was Christ.> Pilate sentences him to be crucified <yielding to the pressure of our authorities>. Yet those who loved him continued to do so up to this day. <On the third day he appeared to them alive, even as the inspired prophets had proclaimed concerning him and many of his miracles.> There are still the so-called Christians who call themselves by this name” (Judean Antiquities, 18,3,3).

It is believed that this paragraph has been preserved almost intact; possible errors are marked by triangular brackets.

Let us compare this passage with the same passage from Josephus Flavius as quoted in the version of Agapius of Hierapolis (died 942 NE):

“At this time there lived a wise man, whose name was Jesus. He led a sinless life and and was known for his virtues. Many Jews and non-Jews became his disciples. Pilate condemned him to death through crucifixion, but those who were his disciples continued to spread his teaching. They said he appeared to them three days after his crucifixion and was alive. That is why, it is believed, that he was the Messiah whose wonderful deeds were foretold by the prophets” (World History [Book of the Titles], 2).

This “testimonium Flavianum” is cited in other sources as well, with slight variations: Eusebius of Caesarea (Church History, 1,11), Hermias Sozomen (Church History, 1,1), Michael Glika (Chronography, 3), Michael Syrian (Chronicle, I), Gregorius Abū’l-Faraj bin hārūn al-Malaṭī (The Lampstand of the Sanctuary).

However, Josephus does not provide the exact dates for the life of Jesus Christ; he only describes His execution under Pontius Pilate. Yet he gives a number of chronological pointers of a different kind, which do not directly relate to Jesus but can help to clarify certain dates in the Gospel narrative. We will analyze them in detail in later chapters.

The problems of chronology in the Gospels

The New Testament chronology remains one of the major challenges for the Biblical studies, and some of its issues have not been solved to this day. The obvious reason for this is the almost complete absence of datings in the Gospel narratives. The only exception is the date for the baptism of Jesus Christ mentioned by he apostle Luke (see Lk 3:1—3; 3:21). Scholars are still undecided as to the exact time of the birth of Jesus Christ, and date of death of Jesus still causes a lot of controversy.

Problematic as it is to recreate the Gospel chronology, this challenge has a flipside: if we eventually succeed in establishing a version that explains all the intricacies of the historical data of the life of Jesus Christ, it will be the only true one.

So, we will start with analyzing all possible variants of the Gospel dates, proceeding from simple to complex, so that we can finally develop a concept that will help to resolve the problem.

The baptism of Jesus Christ

The ministry of Jesus began right after He was baptized by John the Baptist. The time of the ministry of John the Baptist is indicated by the apostle and evagelist Luke:

“Now in the fifteenth year of the reign of Tiberius Caesar, Pontius Pilate being governor of Judaea, and Herod being tetrarch of Galilee, and his brother Philip tetrarch of Ituraea and of the region of Trachonitis, and Lysanias the tetrarch of Abilene, Annas and Caiaphas being the high priests, the word of God came unto John the son of Zacharias in the wilderness. And he came into all the country about Jordan, preaching the baptism of repentance for the remission of sins…” (Lk 3:1—3). The baptism of the Lord happened at the same time: “Now when all the people were baptized, it came to pass, that Jesus also being baptized, and praying…” (Lk 3:21).

The Roman emperor Tiberius (42 BNE — 37 NE) came to power in 14 NE. The 15th year of his reign was the 28th year NE. So, this must be the date for the baptism of Jesus Christ. According to some scholars, the baptism of Jesus Christ took place in 29 NE, if you put it at the end of the 15th year of the reign of Tiberius. Others shift it to the 27th year NE, considering the fact that, starting 13 NE, Tiberius was a co-regent with the emperor Octavian Augustus. There are also those who are trying to move the beginning of the co-regency of Tiberius to 12 NE, and even to 11 NE. As a rule, they quote Gaius Suetonius Tranquill and Gaius Velleius Paterculus (Suetonius. De vita Caesarum. Tiberius, 21; Velleius Paterculus. Historia Romana, II,121), however, the indicated sources only speak of the authority of Tiberius in the provinces, so the shift of the beginning of his reign to years 11 — 12 NE seems too far-fetched. Therefore, the range 27 — 29 NE makes more sense as the possible time interval for the Lord’s baptism.

Then Luke adds: “And Jesus himself began to be about thirty years of age…” (Lk 3:23). It is easy to see that the date for the birth of Jesus Christ should be around 3 BNE, plus or minus several years.

The sevens of Daniel

Let us examine the passage from the Book of Daniel predicting the time of the coming of Christ:

“Seventy weeks are determined upon thy people and upon thy holy city, to finish the transgression, and to make an end of sins, and to make reconciliation for iniquity, and to bring in everlasting righteousness, and to seal up the vision and prophecy, and to anoint the most Holy. Know therefore and understand, that from the going forth of the commandment to restore and to build Jerusalem unto the Messiah the Prince shall be seven weeks, and threescore and two weeks: the street shall be built again, and the wall, even in troublous times. And after threescore and two weeks shall Messiah be cut off, but not for himself: and the people of the prince that shall come shall destroy the city and the sanctuary; and the end thereof shall be with a flood, and unto the end of the war desolations are determined. And he shall confirm the covenant with many for one week: and in the midst of the week he shall cause the sacrifice and the oblation to cease, and for the overspreading of abominations he shall make it desolate, even until the consummation, and that determined shall be poured upon the desolate” (Dan 9:24—27).

According to Dan 9:25, “from the going forth of the commandment to restore and to build Jerusalem unto the Messiah the Prince shall be seven weeks, and threescore and two weeks”, that is (7+62) *7=483 years.

As we can see in the Book of Ezra, the Persian King Artaxerxes I Longimanus issued the corresponding decree in the seventh year of his reign: